Dubgall mac Somairle

Whilst it is possible that Dubgall retained a degree of royal authority after Somairle's death, it is evident that his maternal uncle Rǫgnvaldr Óláfsson seized the kingship before being defeated by Guðrøðr.

Whilst Somairle appears to have been a religious traditionalist, his descendants associated themselves with reformed monastic orders from continental Europe.

Although the division of Clann Somairle territories is uncertain, it is possible that Dubgall held Lorne on the mainland, and the Mull group of islands in the Hebrides.

[22] According to the thirteenth- to fourteenth-century Chronicle of Mann, the couple had several sons: Dubgall, Ragnall, Aongus, and Amlaíb.

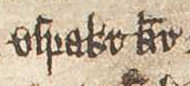

[26] The mixture of Gaelic and Scandinavian names borne by Somairle and his sons appears to exemplify the hybrid Norse-Gaelic milieu of the Isles.

According to the chronicle, Somairle's fleet numbered eighty ships, and when the fighting concluded, the feuding brothers-in-law divided the Kingdom of the Isles between themselves.

[51][note 5] Although the precise partitioning is unrecorded and uncertain, the allotment of lands seemingly held by Somairle's descendants in the twelfth- and thirteenth centuries could be evidence that he and his son gained the southernmost islands of the Hebrides, whilst Guðrøðr retained the northernmost.

[80] The various depictions of Somairle's forces—stated to have been drawn from Argyll, Dublin, and the Isles—appear to reflect the remarkable reach of power that this man possessed at his peak.

[87] Although it is conceivable that Dubgall was able to secure power following his father's demise,[88] it is evident from the Chronicle of Mann that the kingship was seized before the end of the year by Guðrøðr's brother, Rǫgnvaldr Óláfsson.

[93] At one point, after noting this 1156 segmentation, the chronicle laments the "downfall" of the Kingdom of the Isles from the time Somairle's sons "took possession of it".

Although the Chronicle of Mann appears to reveal that Dubgall was the senior dynast in the 1150s,[97] his next and last attestation fails to accord him a royal title.

[103][note 9] Whilst the division of territories amongst later generations of Clann Somairle can be readily discerned, such boundaries are unlikely to have existed during the chaotic twelfth century.

The source further claims that he had no right of inheritance in the Isles on account of illegitimacy, and thus depicts Dubgall's control of the Mull group of islands as a baseless extension of authority at the expense of legitimate members of Clann Somairle.

[123] Following Dubgall's part in his father's coup of 1156, Dubgall's next and last attestation occurs in 1175,[124] when he visited Durham Cathedral upon the eve of the feast of St Bartholomew (23 August), with the Durham Cantor's Book recording his gift of two gold rings and the pledge of 1 mark annuity to St Cuthbert for the rest of his life.

[128] The text specifies that Dubgall's gift was made "at the feet of the saint", suggesting that the ceremony took place before an image of St Cuthbert, or (perhaps more likely) at his shrine.

[135] Before the close of the twelfth century, however, evidence of a new ecclesiastical jurisdiction—the Diocese of Argyll—begins to emerge during ongoing contentions between Clann Somairle and the Crovan dynasty.

[136] Although the early diocesan succession of Argyll is uncertain,[137] the jurisdiction itself appears to have lain outwith the domain of the Crovan dynasty, allowing Clann Somairle to readily act as religious patrons without outside interference.

[144][note 14] The foundation of the Diocese of Argyll appears to have been a drawn-out and gradual process that is unlikely to have been the work of a single individual[151]—be he Somairle,[152] Ragnall,[153] or Dubgall himself.

[157] Although the early diocese suffered from prolonged vacancies—with only two bishops are recorded to have occupied the see before the turn of the mid thirteenth century[158]—over time it became firmly established in the region, allowing the Clann Somairle leadership to retain local control of ecclesiastical power and prestige.

[164] In any case, it is evident that Christian was ousted and replaced by a Manxman, Michael,[166] who appears to have been a candidate backed by the Crovan dynasty,[167] represented by the recently inaugurated Rǫgnvaldr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles.

[170][note 17] Compared to his immediate descendants, who associated themselves with reformed monastic orders from continental Europe, Somairle appears have been something a religious traditionalist.

[178] Since the charter reveals that the monastery received substantial endowments from throughout the Clann Somairle domain, it is likely that the foundation was supported by other leading members the kindred,[179] such as Dubgall (if he were still alive) or Donnchad.

[182] In any event, the charter placed the monastery under the protection of Pope Innocent III, which secured its episcopal independence from the Diocese of the Isles.

[183] As such, the price for the privilege of Iona's papal protection appears to have been the adoption of the Benedictine Rule, and the supersession of the island's centuries-old institution of St Columba.

[188] The same source describes Bethóc as "a religious woman and a Black Nun",[189] whilst the Sleat History states that she was a prioress on Iona.

[190] Although these accounts are somewhat suspect—as the colour black refers to Benedictines not Augustinians[191]—Bethóc's historicity is corroborated by an inscription upon her tombstone, transcribed in the seventeenth-century as: "Behag nijn Sorle vic Ilvrid priorissa".

[192][note 19] Dubgall's donation to the cult of St Cuthbert in Durham, together with the establishment of a Benedictine monastery and an Augustinian nunnery on Iona, are evidence of fundamental ecclesiastical changes affecting the Norse-Gaelic society of the Isles in the twelfth- and thirteenth centuries.

[228] Several late mediaeval pedigrees—such as those preserved by National Library of Scotland Advocates' 72.1.1 (MS 1467) and the Book of Lecan—identify Dubgall's descendants variously as Clann Somairle.

[239] About three and a half decades after Dubgall's final notice, several historical sources appear to indicate that kin-strife amongst Clann Somairle was a cause of increasing instability in the Isles: for example the fifteenth- to sixteenth-century Annals of Ulster reports that Ragnall's sons attacked the men of Skye in 1209, whilst the Chronicle of Mann relates that Aongus—along with his three sons—fell in battle on the same island in 1210.

By the 1240s, for example, Clann Dubgaill was the dominant kindred on Scotland's western seaboard, and had begun to align itself with leading families in the eastern and lowland regions of the Scottish realm.