Dutch Formosa

The Dutch Republic and England came, at the beginning of the 17th century, inevitably in conflict with the forces of Spain and Portugal, in various parts of the world, as they further expanded their area of naval expeditions outside of Europe.

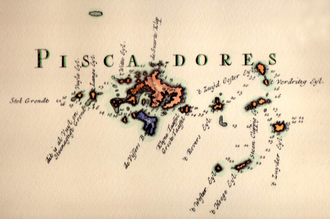

In a 1604 expedition from Batavia (the central base of the Dutch in Asia), Admiral Wybrand van Warwijk set out to attack Macau, but his force was waylaid by a typhoon, driving them to the Pescadores (Penghu), a group of islands 30 miles (50 km) west of Formosa (Taiwan).

[30] Some Dutch missionaries were killed by aboriginals whom they had tried to convert: "The catechist, Daniel Hendrickx, whose name has been often mentioned, accompanied this expedition to the south, as his great knowledge of the Formosa language and his familiar intercourse with the natives, rendered his services very valuable.

The loss of the Japanese trade made the Taiwanese colony far less profitable and the authorities in Batavia considered abandoning it before the Council of Formosa urged them to keep it unless they wanted the Portuguese and Spanish to take over.

[22] In July 1626, the Council of Formosa ordered all Chinese individuals living or trading in Taiwan to obtain a license to "distinguish the pirates from the traders and workers".

The fortification at Keelung was abandoned because the Spanish lacked the resources to maintain it, but Fort Santo Domingo in Tamsui was seen as a major obstacle to Dutch ambitions on the island and the region in general.

Following this victory, the Dutch set about bringing the northern villages under their banner in a similar way to the pacification campaign carried out in the previous decade in the south.

[39] In 1644, a pirate named Kinwang who had been sacking aboriginal villages in Formosa since the previous year, stranded in the Bay of Lonkjauw and the natives captured him, handing him over to the Dutch.

After his capture he was executed, and a document in his possession was found appealing to the Chinese of Formosa, promising to pay them richly and capitalizing on frustrations of Dutch taxes and their restrictions on trading and hunting.

Most of the immigrants were young single males who were discouraged from staying on the island, often referred to by Han as "The Gate of Hell" for its reputation in taking the lives of sailors and explorers.

[41] On 7 September 1652, it was reported that a Chinese farmer, Guo Huaiyi, had gathered an army of peasants armed with bamboo spears and harvest knives to attack Sakam.

[42] In May 1654, Fort Zeelandia was afflicted by a swarm of locusts, then a plague that killed thousands of natives, Dutch, and Chinese, and then an earthquake that destroyed homes and buildings with aftershocks lasting seven weeks.

When Beijing fell in 1644 to rebels, Chenggong and his followers declared their loyalty to the Ming dynasty and he was bestowed the title Guoxingye (Lord of the Imperial surname), pronounced "Kok seng ia" in southern Fujianese.

The Dutch held out at Keelung until 1668, when aborigine resistance (likely incited by Zheng Jing),[59] and the lack of progress in retaking any other parts of the island persuaded the colonial authorities to abandon this final stronghold and withdraw from Taiwan altogether.

[66][67] Despite this, trade with the EIC was limited due to the Zheng monopoly on sugarcane and deer hide as well as the inability of the English to match the price of East Asian goods for resale.

[73] Benefitting from triangular trade between themselves, the Chinese and the Japanese, plus exploiting the natural resources of Formosa, the Dutch were able to turn the malarial sub-tropical bay into a lucrative asset.

After establishing their fortress, the Dutch realised the potential of the vast herds of the native Formosan sika deer (Cervus nippon taioanus) roaming the western plains of the island.

[79] Although the rates of such taxation are unknown as there are no records, the Dutch must have made a lot of profit from the export duties received by Chinese and Japanese traders.

[79] Prior to the arrival of the Dutch, Taiwan was almost exclusively populated by Taiwanese aborigines; Austronesian peoples who lived in a hunter-gatherer society while also practicing swidden agriculture.

The number of soldiers stationed on the island waxed and waned according to the military needs of the colony, from a low of 180 troops in the early days to a high of 1,800 shortly before Koxinga's invasion.

According to a report, "soldiers not only confiscate their hoofdbrieven, in order to prosecute them and demand a fine, but also take their meager possessions, seizing anything they can get their hands on, whether chickens, pigs, rice, clothing, bedding, or furniture.

[109][110] Eighteen Quinamese and Java slaves were involved in a Dutch attack against the Tammalaccouw aboriginals, along with 110 Chinese and 225 troops under Governor Traudenius on 11 January 1642.

[111] Seven Quinamese and three Javanese persons were involved in a gold hunting expedition along with 200 Chinese individuals and 218 troops under Senior Merchant Cornelis Caesar from November 1645 to January 1646.

[124] Upon arrival, the first indigenous groups the Dutch made contact with were the Sinkang (新港), Backloan (目加溜灣), Soelangh (蕭), and Mattauw (麻豆).

[125] This interventionist process included the massacre of the indigenous people inhabiting Lamay Island in 1642 by Dutch forces led by Officer Francois Caron.

[30] After these events, the native aborigines eventually were forced into pacification under military domination and were used for a variety of labor activities during the span of Dutch Formosa.

The Formosans practiced various activities which the Dutch perceived as sinful or at least uncivilised, including mandatory abortion (by massage) for women under 37,[129] frequent marital infidelity,[129] non-observation of the Christian Sabbath and general nakedness.

[130] The unique variety of trading resources (in particular, deerskins, venison and sugarcane), as well as the untouched nature of Formosa led to an extremely lucrative market for the VOC.

A journal record written by the Dutch governor Pieter Nuyts holds that "Taiwan was an excellent trading port, enabling 100 per cent profits to be made on all goods".

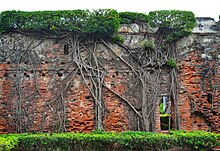

The building was later used by the British consulate[136] until the United Kingdom severed ties with the KMT (Chinese Nationalist Party or Kuomintang) regime and its formal relationship with Taiwan.