Dutch invasions of Brazil

[5] The success of this project led to the founding of the Dutch West India Company in 1621, which was responsible for the monopoly of the slave trade for twenty-four years in the Americas and Africa.

One of them, written by the Portuguese merchant Lopes Vaz, emphasized the qualities of the wealthy town of Olinda by saying that "Pernambuco is the most important city on the entire coast".

The fleet left with a hefty amount of sugar, brazilwood, cotton and high-priced products; only one small ship didn't reach its destination.

The profit for the investors, including Thomas Cordell, then mayor of London, and John Wattas, a city councilor, was estimated at more than 51,000 pounds sterling.

[6][7] After Lancaster's visit, the Captaincy of Pernambuco organized two armed companies to defend the region, each with 220 musketeers and arquebusiers, one based in Olinda and the other in Recife.

[6][7] According to some authors, while passing along the coast of Brazil, Admiral Olivier van Noort, leading his expedition, attempted an invasion of Guanabara Bay.

[8][9] With the crew sick with scurvy, the fleet asked for permission to obtain fresh supplies in Guanabara Bay, which was denied by the captaincy's government, in accordance with instructions received from the Portuguese Crown.

[9] In the 1648 edition of Miroir Oost & West-Indical (originally published in Amsterdam in 1621 by Ian Ianst), Spielbergen's narrative is illustrated by an engraving of São Vicente, which portrays the incident in Santos.

[10] In the vicinity of Almeirim (formerly Aldeia de Paru), the Dutch, accompanied by some Englishmen and led by Pieter Ita, made an attempt to settle with the construction of the Morro da Velha Pobre Fort in 1623.

The governor of the Captaincy of Pernambuco, Matias de Albuquerque, was appointed governor-general and began to administer the colony from Olinda and send significant reinforcements to the resistance based in Arraial do Rio Vermelho and Recôncavo.

[12] The huge cost of the invasion of the lands of Bahia was recovered four years later in an act in the Caribbean Sea, when Admiral Piet Heyn, in the service of the WIC, intercepted and sacked the Spanish fleet that was carrying the annual shipment of silver mined from the American colonies.

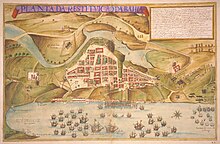

A new squadron of sixty-seven ships and around seven thousand men - the largest ever seen in the colony - under the command of Admiral Hendrick Lonck, invaded Pernambuco and, in February 1630, conquered Olinda and then captured Recife in March.

Using indigenous combat tactics, such as guerrilla warfare, they confined the invaders inside the fortifications on the urban perimeter of Olinda and its port, Recife.

[15] The so-called "ambush tactics" were small groups of ten to forty highly mobile men who attacked the Dutch by surprise and then retreated at speed, regrouping for new battles.

[16] Military leaders such as Martim Soares Moreno, Filipe Camarão, Henrique Dias and Francisco Rebelo (also known as Rebelinho) stood out during this phase of Luso-Brazilian resistance.

[19] In the Insurrection of Pernambuco (also known as the War of Divine Light), the movement that expelled the Dutch from Brazil was led by the plantation owners André Vidal de Negreiros and João Fernandes Vieira, the Afro-descendant Henrique Dias[20] and the native Filipe Camarão.

Contrary to what he had advocated in his political "testament", the company's new managers began to demand the liquidation of debts owed to defaulting plantation owners, a policy that led to the Insurrection of Pernambuco in 1645 and culminated in the extinction of Dutch rule after the second Battle of Guararapes.

[20] Formally, the surrender was signed on January 26, 1654, in the Taborda Hill, but it only became fully effective on August 6, 1661, with the signing of the Treaty of The Hague, in which Portugal agreed to compensate the Netherlands with two colonies, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and the Maluku Islands (part of present-day Indonesia), and eight million guilders, equivalent to sixty-three tons of gold, paid in installments over forty years under the threat of invasion by the Navy.

According to a traditional historiographical current in the military history of Brazil, the movement also marked the germ of Brazilian nationalism, as whites, Africans and indigenous people merged their interests in expelling the invader.

With difficulties in acquiring labor and without mastering the refining and distribution process and capital to invest, Portuguese sugar was unable to compete on the international market, immersing Brazil's economy (and Portugal's) in a crisis that would last through the second half of the 17th century until the discovery of gold in Minas Gerais.

Since this haplogroup is more common in northeastern Brazil (19%) than in Portugal (13%), the researchers hypothesized that this "excess" could be due to the genetic influence of the Dutch colonizers who came to the region in the 17th century.