Dymaxion map

The March 1, 1943, edition of Life magazine included a photographic essay titled "Life Presents R. Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion World", illustrating a projection onto a cuboctahedron, including several examples of possible arrangements of the square and triangular pieces, and a pull-out section of one-sided magazine pages with the map faces printed on them, intended to be cut out and glued to card stock to make a three-dimensional cuboctahedron or its two-dimensional net.

[1] Fuller applied for a patent in the United States in February 1944 for the cuboctahedron projection, which was issued in January 1946.

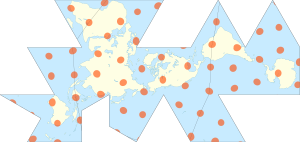

Peeling the solid apart in a different way presents a view of the world dominated by connected oceans surrounded by land.

Showing the continents as "one island earth" also helped Fuller explain, in his book Critical Path, the journeys of early seafaring people, who were in effect using prevailing winds to circumnavigate this world island.

A conformal map preserves angles and local shapes from the sphere at the expense of increasing the scale distortion near the vertices of the icosahedron.

[11] Comparison of the Fuller projection and Strebe's Dymaxion-like conformal projection with Tissot's indicatrices at 30° intervals A 1967 Jasper Johns painting, Map (Based on Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion Airocean World), depicting a Dymaxion map, hangs in the permanent collection of the Museum Ludwig in Cologne.

[16] In 2013, to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the publication of the Dymaxion map in Life magazine, the Buckminster Fuller Institute announced the "Dymax Redux", a competition for graphic designers and visual artists to re-imagine the Dymaxion map.