Early American publishers and printers

[9] According to Wroth, however, the overall subject of early American printing and publishing as it affected political and social issues in the colonies and how it ultimately led to a revolution, which is the focus of this article, has been pursued with a "noticeable reluctance".

[4][10] Newspapers in colonial America served to disseminate vital political, social and religious information that explicitly appealed to the colonist's growing sense of independence and unity with other Americans.

[14] On September 25, 1690, the first newspaper to emerge in the British colonies in America was the Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick, printed and published in Boston by Richard Pierce for Benjamin Harris.

By 1774, the idea for an independent union was not yet one of complete separation from the mother country in England and had assumed that the colonies would still be an essential component of the British Empire and still under the authority of the King and Parliament.

Word of this incursion quickly spread in newspapers and broadsides and in response the various colonies, in support of Massachusetts whose trade had largely been halted, sent representatives to Philadelphia and formed the First Continental Congress.

[39] The articles in this Association were met with mixed reactions from the colonists, and from various American and British individuals in Britain, with letters for and against the measure appearing in colonial newspapers, with criticisms coming mostly from moderate or loyalist presses.

[40] On April 22, 1775, three days after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the Virginia Gazette reported that a large quantity of gunpowder in Williamsburg had been stolen during the night by order of Lord Dunmore.

Franklin's newspaper had been current for only four months when it was ordered shut down, where he was "... strictly forbidden by this Court to print or publish the New-England Courant, or any other pamphlet or paper of the like nature, except it be first supervised by the Secretary of this Province; and the Justices of His Majesty's Sessions of the Peace for the County of Suffolk ..."[45][46][47] On October 2, 1729, Samuel Keimer, the owner of The Pennsylvania Gazette in Philadelphia, who failed to make a success out of this newspaper, fell into debt and before fleeing to Barbados sold the Gazette to Benjamin Franklin and his partner Hugh Meredith.

After several failed appeals to the Court, they finally conceded to his wishes, with a few restrictions in place,[77] allowing Johnson in 1674 to become the first printer in the American colonies to operate his own press.

[90] Religious perspectives became prominent in colonial American literature during the later 17th-century and into the 18th-century, and were mostly found in Puritan writings and publications,[93][g] often resulting in charges of libel and sedition levied by the British Crown.

In 1637 King Charles passed a Star Chamber decree outlining 33 regulations that provided for the complete control and censoring of any religious, political or other literature they deemed seditious or otherwise questionable.

[97][98][99] In 1663, English Puritan missionary John Eliot over the course of forty years, attracted some eleven hundred Indians to the Christian faith, and established fourteen reservations, or "praying towns" for his followers.

Like many Tories he believed, as he asserted in this pamphlet, that the Revolution was, to a considerable extent, a religious quarrel, caused by Presbyterians[j] and Congregationalists and the circular letters and other accounts they had printed and distributed.

[130] The passage of the act also caused many printers to suspend their publications rather than to pay what they strongly felt was an unfair tax and an imposition on their livelihood, subsequently uniting them in their opposition to its legislation.

The damning paragraph gave great offense to the royal government of that province, and its publisher, Anthony Henry, was called to account for printing what the Crown considered to be sedition.

"[151][152] In the years leading up to, and during the American Revolution, hundreds of pamphlets were printed covering a variety of themes about religion, common law, politics, natural rights and the enlightenment, which were largely written in relation to revolutionary thought.

Thomas Paine's 1776 work, Common Sense, outlined moral and political arguments and is considered "the most incendiary and popular pamphlet of the entire revolutionary era", and was printed by Robert Bell.

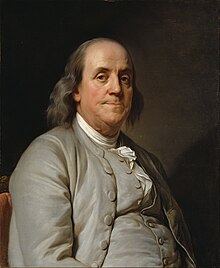

Before the ideals of independence and revolution came to be embraced among the colonists the differences in their settlements and forms of government, in religion, culture, trade and domestic policy, were so great that Benjamin Franklin, who well understood the situation, said, that nothing but the oppression of the entire country would ever unite them.

[163] At the outbreak of war at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, it became clearly evident that the Whigs dominated the press and postal networks and could use them to subvert Tory and Loyalist polemics.

After the Declaration of Independence was officially issued to the British Crown, only 15 Loyalist newspapers emerged at various times and places, but none of them managed to publish continuously in the instability and uncertainty of war from 1776 to 1783.

Adams contributed a forceful letter of December 19, 1768, to this newspaper, and according to historian James Kendall Hosmer, it would "perhaps be impossible to find a better illustration of the superior political sense of the New Englanders".

[170] The office of the Boston Gazette on Court Street, also functioned as a meeting place for various revolutionary figures, including Joseph Warren, James Otis,[p] Josiah Quincy, John Adams, Benjamin Church, and other patriots scarcely less conspicuous.

The account that appeared in the Independent Chronicle of April 19, 1781, though generally informative, was based on a report written in haste by Nathanael Greene who had incomplete knowledge of troop strengths and casualties.

[184] To convince the people of New York and other states that ratification of the U.S. Constitution was in their best interest, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay wrote a series of essays entitled The Federalist Papers.

[186] The Federalist papers were challenged by the vigorous writings of Richard Henry Lee and Elbridge Gerry, which further demonstrated the importance of the press and its value in obtaining political ends.

After the swearing in ceremony Washington entered the Senate chamber and delivered the first presidential inaugural address The entire event and speech was covered in an eyewitness report on May 6, 1789, in the Massachusetts Centinel.

[201] The Alien and Sedition Acts were four laws were passed by the Fifth U.S. Congress under President John Adams in 1798 during the undeclared Quasi War with France,[s] with the claim that they were directed at the French and their sympathizers in the United States.

Much of the impetus for passage of the Acts, however, was largely the result of partisan newspapers which were highly critical of President Adams and other federalists over their apparent eagerness to engage France in an actual declared War.

[213] Pennsylvania Chief Justice Thomas McKean, in a 1798 libel case against William Cobbett, publisher of the Peter Porcupine's Gazette, in Philadelphia, which was widely considered a scandalous and inciteful publication, once remarked: "Every one who has in him the sentiments either of a Christian or a gentleman cannot but be highly offended at the envenomed scurrility that has raged in pamphlets and newspapers printed in Philadelphia for several years past, insomuch that libelling has become a national crime, and distinguishes us not only from all the states around us, but from the whole civilized world.

In June 1788, he read a treatise before the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia entitled, "Description of the Process to be Observed in Making Large Sheets of Paper in the Chinese Manner, with one Smooth Surface.