Scotland in the early modern period

[7] Failure of the pro-English to deliver a marriage between the infant Mary and Edward, the son of Henry VIII of England, that had been agreed under the Treaty of Greenwich (1543), led within two years to an English invasion to enforce the match, later known as the "rough wooing".

In 1547, after the death of Henry VIII, forces under the English regent Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset were victorious at the Battle of Pinkie, followed up by the occupation of the strategic lowland fortress of Haddington and recruitment of "Assured Scots".

[11] From 1554, Marie of Guise took over the regency, maintaining a difficult position, partly by giving limited toleration to Protestant dissent and attempting to diffuse resentment over the continued presence of French troops.

[13] During the sixteenth century, Scotland underwent a Protestant Reformation that created a predominately Calvinist national kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterian in outlook, severely reducing the powers of bishops, although not abolishing them.

In the earlier part of the century, the teachings of first Martin Luther and then John Calvin began to influence Scotland, particularly through Scottish scholars who had visited continental and English universities and who had often trained in the Catholic priesthood.

At this point the majority of the population was probably still Catholic in persuasion and the kirk would find it difficult to penetrate the Highlands and Islands, but began a gradual process of conversion and consolidation that, compared with reformations elsewhere, was conducted with relatively little persecution.

As neither side wished to push the matter to a full military conflict, a temporary settlement was concluded, known as the Pacification of Berwick in June 1639, and the First Bishops' War ended with the Covenanters retaining control of the country.

He was able to dictate terms to the Covenanters, but as he moved south, his forces, depleted by the loss of MacColla and the Highlanders, were caught and decisively defeated at the Battle of Philiphaugh by an army under David Leslie, nephew of Alexander.

[59] In the early 1680s a more intense phase of persecution began, in what was later to be known in Protestant historiography as "the Killing Time", with dissenters summarily executed by the dragoons of James Graham, Laird of Claverhouse or sentenced to transportation or death by Sir George Mackenzie, the Lord Advocate.

[60] In England, the Exclusion crisis of 1678–1681 divided political society into Whigs (given their name after the Scottish Whigamores), who attempted, unsuccessfully, to exclude the openly Catholic Duke of Albany from the succession, and the Tories, who opposed them.

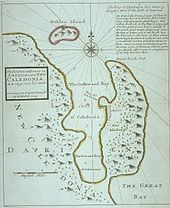

The "Company of Scotland" invested in the Darien scheme, an ambitious plan devised by William Paterson, the Scottish founder of the Bank of England, to build a colony on the Isthmus of Panama in the hope of establishing trade with the Far East.

Since the capital resources of the Edinburgh merchants and landholder elite were insufficient, the company appealed to middling social ranks, who responded with patriotic fervour to the call for money; the lower orders volunteered as colonists.

The East India Company saw the venture as a potential commercial threat and the government were involved in the War of the Grand Alliance from 1689 to 1697 against France and did not want to offend Spain, which claimed the territory as part of New Granada and the English investors withdraw.

Poorly equipped; beset by incessant rain; suffering from disease; under attack by the Spanish from nearby Cartagena; and refused aid by the English in the West Indies, the colonists abandoned their project in 1700.

[69] The cost of £150,000 put a severe strain on the Scottish commercial system and led to widespread anger against England, while, seeing the impossibility of two economic policies, William was prompted to argue for political union shortly before his death in 1702.

[12] The accession of James VI to the English throne made the border less significant in military terms, becoming, in his phrase the "middle shires" of Great Britain, but it remained a jurisdictional and tariff boundary until the Act of Union in 1707.

Estimates based on English records suggest that by the end of the Middle Ages, the Black Death and subsequent recurring outbreaks of the plague, may have caused the population of Scotland to fall as low as half a million people.

James became obsessed with the threat posed by witches and, inspired by his personal involvement, in 1597 wrote the Daemonologie, a tract that opposed the practice of witchcraft and which provided background material for Shakespeare's Tragedy of Macbeth.

[138] The system was largely able to cope with the general level of poverty and minor crises, helping the old and infirm to survive and provide life support in periods of downturn at relatively low cost, but was overwhelmed in the major subsistence crisis of the 1690s.

[173] In 1605 the professionalisation of the bench led to entry requirements in Latin, law and a property qualification of £2,000, designed to limit the danger of bribery, helping to create an exclusive, wealthy and powerful and professional caste, who also now dominated government posts in a way that the clergy had done in the Middle Ages.

[198] As armed conflict with Charles I in the Bishops' Wars became likely, hundreds of Scots mercenaries returned home from foreign service, including experienced leaders like Alexander and David Leslie and these veterans played an important role in training recruits.

[211] Scottish seamen received protection against arbitrary impressment by English men of war, but a fixed quota of conscripts for the Royal Navy was levied from the sea-coast burghs during the second half of the seventeenth century.

After the religious and political upheavals of the seventeenth century, the universities recovered with a lecture-based curriculum that embraced economics and science, offering a high quality liberal education to the sons of the nobility and gentry.

Perhaps the most significant intellectual figure of this era in Scotland was David Hume (1711–76) whose Treatise on Human Nature (1738) and Essays, Moral and Political (1741) helped outline the parameters of philosophical empiricism and scepticism.

[243] As a patron of poets and authors James V supported William Stewart and John Bellenden, who translated the Latin History of Scotland compiled in 1527 by Hector Boece, into verse and prose.

When he married Mary of Guise, Giovanni Ferrerio, an Italian scholar who had been at Kinloss Abbey in Scotland, dedicated to the couple a new edition of his work, On the true significance of comets against the vanity of astrologers.

[248] By the late 1590s his championing of his native Scottish tradition was to some extent diffused by the prospect of inheriting of the English throne,[249] and some courtier poets who followed the king to London after 1603, such as William Alexander, began to anglicise their written language.

[255] Allan Ramsay (1686–1758) laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, as well as leading the trend for pastoral poetry, helping to develop the Habbie stanza as a poetic form.

One result of this was the flourishing of Scottish Renaissance painted ceilings and walls, with large numbers of private houses of burgesses, lairds and lords gaining often highly detailed and coloured patterns and scenes, of which over a hundred examples survive.

These were undertaken by unnamed Scottish artists using continental pattern books that often led to the incorporation of humanist moral and philosophical symbolism, with elements that call on heraldry, piety, classical myths and allegory.