Pail closet

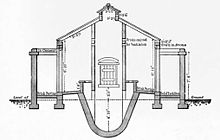

The "closet" (a word which had long meant "toilet" in one usage) was a small outhouse (privy) which contained a seat, underneath which a portable receptacle was placed.

Some manufacturers lined the pail with absorbent materials, and other designs used mixtures of dry earth or ash to disguise the smell.

Improved water supplies and sewerage systems in England led directly to the replacement of the pail closet during the early 20th century.

Pail closets were used to dispose of human excreta, dirty water, and general household waste such as kitchen refuse and sweepings.

An investigation of the condition of the city's sewer network revealed that it was "choked up with an accumulation of solid filth, caused by overflow from the middens.

[4] The soil surrounding the old middens was cleared out, connections with drains and sewers removed and dry closets erected over each site.

A contemporary estimate stated that the installation of about 25,000 pail closets removed as much as 3,000,000 imperial gallons (14,000,000 L) of urine and accompanying faeces from the city's drains, sewers and rivers.

A Mr Redgrave, in a speech to the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1876, said that the midden closet represented "... the standard of all that is utterly wrong, constructed as it is of porous materials, and permitting free soakage of filth into the surrounding soil, capable of containing the entire dejections from a house, or from a block of houses, for months and even years".

Later improvements, such as a midden closet built in Nottingham, used a brick-raised seat above a concave receptacle to direct excreta toward the centre of the pit—which was lined with cement to prevent leakage into the surrounding soil.

The design offered a significant improvement over the less advanced midden privy, but the problems of emptying and cleaning such pits remained and thus the pail system, with its easily removable container, became more popular.

Probably the more regular locking of the doors of the closets, which is practiced in Halifax, contributes not a little to the exclusion of the contents of chamber utensils from the pails, less trouble being experienced in casting them into the yard drain.

Manchester Corporation attempted to remove the smell of putrefaction by attaching cinder-sifters to their closets so that fine ash could be poured on top of the excrement.

Each was lined at the sides and bottom with a mixture of refuse, such as straw, grass, street sweepings, wool, hair, and even seaweed.

This lining, which was formed by a special mould and to which sulphate of lime was added, was designed to help remove the smell of urine, slow putrefaction and keep the excreta dry.

Members of the public occasionally complained about the smell, which usually occurred when a pail was left to overflow, such as in winter 1875 when severe weather conditions prevented the horse-pulled collection wagons from reaching the closets.

In his report on the Goux system used in Salford, the epidemiologist John Netten Radcliffe commented: "In every instance where a pail had been in use over two or three days, the capacity of absorption of the liquid dejections, claimed by the patentee for the absorbent material, had been exceeded; and whenever a pail had been four or five days a week in use, it was filled to the extent of two thirds or more of its cavity, with liquid dejections, in which the solid excrement was floating.

In his 1915 essay to the American Public Health Association, author Richard Messer described some of the more commonly encountered problems: Any of these [pails] should be provided with handles and be held in place by guide pieces nailed to the floor.

Wooden boxes are unsatisfactory for they soon become leaky due to warping, are too heavy to handle and hold excreta long enough to permit the breeding of flies.

The lack of proper attention in regard to cleaning is perhaps the principal drawback to this style of privy and one which makes it practically a failure for general use.

The use of pail closets reduced the demand placed upon the area's inadequate sewerage system, but the town suffered with difficulties in the collection and treatment of the night soil.

[23] In Manchester, faced with phenomenal population growth, the council attempted to retain the pail closet system, but following the exposure of the dumping of 30–60 long tons (30–61 t) of human faeces into the Medlock and Irwell rivers at their Holt Town sewage works,[a][24] the council was forced to change their plans.