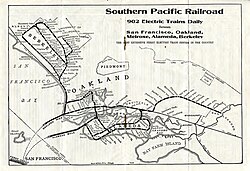

East Bay Electric Lines

With the merger with the Central Pacific, trains would terminate at the Oakland Mole (a long ferry pier into the San Francisco Bay), starting in January of 1882.

[3] The SFO&SJ interurban line was faster, quicker, cleaner, and quieter than the Southern Pacific's steam operations, which paled in comparison.

When the construction of catenary over the new lines was complete, Southern Pacific received a new fleet of 72-foot-long (22 m) steel interurbans from the American Car & Foundry Company in the later months of 1911.

Long term plans called for extensions to Richmond and San Jose (to presumably link up with Southern Pacific's other interurban subsidiary, the Peninsular Railway), which never materialized.

[7] As a result, the company sought to merge East Bay Electric Lines with the rival Key System.

[citation needed] An internal report by Southern Pacific management in 1933 recommended total abandonment of East Bay electric services.

Due to the widespread adoption of the automobile, the Great Depression, and high labor costs,[9] the IER was rapidly losing both money and patronage, so a franchise was granted[when?]

to them for operation on the lower deck of the San Francisco Bay Bridge to the new Transbay Terminal, in order to entice new patrons.

So, the Interurban Electric Railway began construction of a trestle over the Southern Pacific and Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railroad tracks in order to access this new area.

Extra trains for Bay Bridge usage could also be stored here, but this practice was not used by the Sacramento Northern Railroad who preferred to utilize an existing yard.

The Interurban Electric Railway's new route also featured a fly-over bridge over Key System / Sacramento Northern tracks.

Electrification on the bridge would be at 1200 volts for the Sacramento Northern and Interurban Electric Railway, so all trains were also retrofitted to run on this voltage.

Three lines originally terminated at Thousand Oaks in Berkeley, two at 14th and Franklin in Oakland, and two at High Street South in Alameda.

The East Bay Electric Lines had trackage over a series of estuaries and rivers, including the San Francisco Bay, which meant that due to the limitations of the infrastructure over these bodies of water the usual method of center-pole and cross-arm located in between the double-track was given up, in favor of 65-foot-tall (20 m) tall iron poles in a lattice-formation that held up the catenary.

[35] To provide faster transportation on its commuter lines, Southern Pacific purchased steel interurbans from the American Car & Foundry Company (AC&FC).

[34][37][2] When first acquired by the AC&FC, the interurbans were painted an olive green, which was standard among most passenger cars of the time.

These differed from the AC&FC's style because these new interurbans all featured the safer rounded windows in the front and backs in the original construction, and seated only 111 passengers.

[2] In 1926, because of declining patronage, the streetcars were sent to rival Key System for operation on the subsidiary East Bay Street Railways (EBSR).

They were usually put on the end of the train toward Oakland Pier, and most commonly on the 7th St Line as far as Havenscourt or Seminary Avenue.

[23] When plans for longer routes were not implemented,[38][39] 21 of the ACF combos were changed to motors at the time they received their round end windows in the 1920s.

[40] The California Toll Bridge Authority (TBA) funded these changes and received title to 58 cars in return.

Unlike most street railways, work rules dictating operations for employees were of a more restrictive type usually applied to mainline steam railroads, a situation which endured even with electric service.

Tracks on 7th Street west of Broadway were additionally reactivated under Key System cars to serve the ship yards in Oakland.

An excursion train pulled by a steam locomotive was operated over this track in April 1954, by the Bay Area Electric Railroad Association.

The Northbrae Tunnel, which runs between Sutter Street and Solano Avenue underneath the Fountain Roundabout, is one of the most physical remains of the SP/IER.

The northbound portion of the trestle was formerly in use by the Oakland Terminal Railway, a Key System subsidiary meant to handle freight.

[48][better source needed] The southbound portion of the trestle was converted to a road after abandonment, and does not exist anymore aside from a 280 foot long section.

The Emeryville Greenway between 9th Street and Stanford Avenue is a section of former IER right of way that serviced the interurban line to Thousand Oaks.

The SP sent the 2 box motors to the PE,[51] in March and April used 5 trailers for buildings in West Oakland,[52] and stored their remaining 81 cars until they were requisitioned in July and September by the United States Maritime Commission for use in transporting workers to World War II shipyards: 20 trailers to a line in the Portland, Oregon, area and 61 cars to the PE in Southern California where some of them were in use until that system ceased operations in 1961.