East End of London

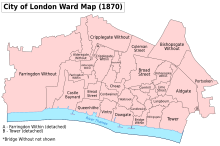

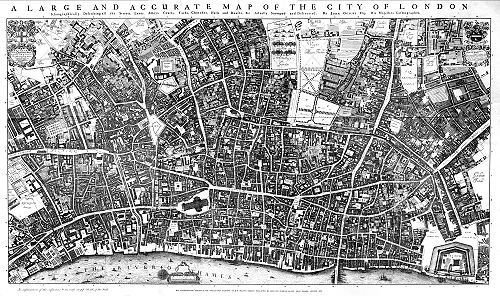

The East End began to emerge in the Middle Ages with initially slow urban growth outside the eastern walls, which later accelerated, especially in the 19th century, to absorb pre-existing settlements.

The area had a strong pull on the rural poor from other parts of England, and attracted waves of migration from further afield, notably Huguenot refugees, Irish weavers, Ashkenazi Jews, and, in the 20th century, Bengalis.

The closure of the last of the Port of London's East End docks in 1980 created further challenges and led to attempts at regeneration, with Canary Wharf and the Olympic Park[1] among the most successful examples.

Paradoxically, while some parts of the East End are undergoing rapid change and are amongst the areas with the highest mean salary in the UK,[2] it also continues to contain some of the worst poverty in Great Britain.

These and other factors meant that industries relating to construction, repair, and victualling of naval and merchant ships flourished in the area but the City of London retained its right to land the goods, until 1799.

Pigs and cows in back yards, noxious trades like boiling tripe, melting tallow, or preparing cat's meat, and slaughter houses, dustheaps, and 'lakes of putrefying night soil' added to the filthA movement began to clear the slums.

[56] Ships continued to be built at the Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company at Blackwall and Canning Town until the yard closed in 1913, shortly after the launch of the Dreadnought Battleship HMS Thunderer (1911).

The devastating closure of the docks and the loss of the associated industries led to the establishment of the London Docklands Development Corporation,[86] which operated from 1981 to 1998; the body was charged with using deregulation and other levers to stimulate economic regeneration.

[92] Weaving was a major industry in areas close to the City but remote from the Thames; the arrival of Huguenot (French Protestant)[93] refugees, many of them weavers, alongside large numbers of their English and Irish[94] counterparts contributed to rapid development in Spitalfields and western Bethnal Green in the 17th century.

[98] The migrants settled in areas already established by the Bengali expatriate community, working in the local docks and Jewish tailoring shops set up to use cotton produced in British India.

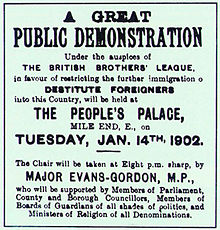

In 1901, Captain William Stanley Shaw and he formed the British Brothers' League which conducted xenophobic agitation against immigrants in the East End, with Jews eventually becoming the main focus.

[107] On 4 October 1936, around 3–5,000 uniformed blackshirts from the British Union of Fascists, led by Oswald Mosley and inspired by German and Italian fascism, assembled to begin an anti-semitic march through the East End.

The Second World War devastated much of the East End, with its docks, railways and industry forming a continual target for bombing, especially during the Blitz, leading to dispersal of the population to new suburbs and new housing being built in the 1950s.

The resulting depopulation accelerated after the Second World War and has only recently begun to reverse, though the Bangladeshi community, now the largest in Tower Hamlets and established East Enders, are beginning to migrate to the eastern suburbs.

Throughout its history, the East End has evolved in response to economic and social change, including migration, with its population being joined by large numbers of people from the UK and overseas.

In 1938, West Ham's Jewish inside-left Len Goulden (born Hackney, raised in Plaistow), scored England's winning goal against Germany in Berlin, in front of 110,000 Germans including Hermann Goerring and Josef Goebbels, in a game Hitler had hoped to use for propaganda purposes.

Timbs noted that "... so strong was the love of cleanliness thus encouraged that women often toiled to wash their own and their children's clothing, who had been compelled to sell their hair to purchase food to satisfy the cravings of hunger".

These actions, combined with the many dock strikes, made the East End a key element in the foundation and achievements of modern socialist and trade union organisations, as well as the Suffragette movement.

[160] After a bitter struggle and the mediation of Cardinal Manning, the London Dock Strike of 1889 was settled with victory for the strikers, and established a national movement for the unionisation of casual workers, as opposed to the craft unions that already existed.

The philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts was active in the East End, alleviating poverty by founding a sewing school for ex-weavers in Spitalfields and building the ornate Columbia Market in Bethnal Green.

[161] Between the 1890s and 1903, when the work was published, the social campaigner Charles Booth instigated an investigation into the life of London poor (based at Toynbee Hall), much of which was centred on the poverty and conditions in the East End.

Unusually, Joseph Sadler Thomas, a Metropolitan Police superintendent of "F" (Covent Garden) Division, appears to have mounted the first local investigation (in Bethnal Green), in November 1830 of the London Burkers.

[202] One of the East End industries that serviced ships moored off the Pool of London was prostitution, and in the 17th century, this was centred on the Ratcliffe Highway, a long street lying on the high ground above the riverside settlements.

This coincided with a project by the philanthropist businessman, Edmund Hay Currie to use the money from the winding up of the Beaumont Trust,[226] together with subscriptions to build a "People's Palace" in the East End.

[49] The problems were exacerbated with the construction of St Katharine Docks (1827)[233] and the central London railway termini (1840–1875) that caused the clearance of former slums and rookeries, with many of the displaced people moving into the East End.

[13] [The] invention about 1880 of the term "East End" was rapidly taken up by the new halfpenny press, and in the pulpit and the music hall ... A shabby man from Paddington, St Marylebone or Battersea might pass muster as one of the respectable poor.

Though the area has been productive of local writing talent, from the time of Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) the idea of 'slumming it' in the 'forbidden' East End has held a fascination for a coterie of the literati.

This latter group particularly became the subject of music hall songs at the turn of the 20th century, with performers such as Marie Lloyd, Gus Elen and Albert Chevalier establishing the image of the humorous East End Cockney and highlighting the conditions of ordinary workers.

The success of Jennifer Worth's memoir Call the Midwife (2002, reissued 2007), which became a major best-seller and was adapted by the BBC into their most popular new programme since the current ratings system began,[241] has led to a high level of interest in true-life stories from the East End.

[242] A raft of similar books was published in the 2000s, among them Gilda O'Neill's best-selling Our Street (2004),[243] Piers Dudgeon's Our East End (2009), Jackie Hyam's Bombsites and Lollipops (2011) and Grace Foakes' Four Meals for Fourpence (reprinted 2011).