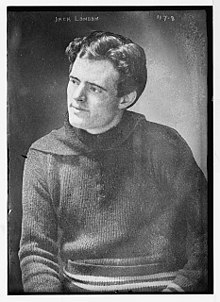

Jack London

[7] London was part of the radical literary group "The Crowd" in San Francisco and a passionate advocate of animal welfare, workers' rights and socialism.

[8][9] London wrote several works dealing with these topics, such as his dystopian novel The Iron Heel, his non-fiction exposé The People of the Abyss, War of the Classes, and Before Adam.

His most famous works include The Call of the Wild and White Fang, both set in Alaska and the Yukon during the Klondike Gold Rush, as well as the short stories "To Build a Fire", "An Odyssey of the North", and "Love of Life".

[15] In 1897, when he was 21 and a student at the University of California, Berkeley, London searched for and read the newspaper accounts of his mother's suicide attempt and the name of his biological father.

After grueling jobs in a jute mill and a street-railway power plant, London joined Coxey's Army and began his career as a tramp.

[32] While living at his rented villa on Lake Merritt in Oakland, California, London met poet George Sterling; in time they became best friends.

[33] The Crowd gathered at the restaurants (including Coppa's[34]) at the old Montgomery Block[35][36] and later was a: Bohemian group that often spent its Sunday afternoons picnicking, reading each other's latest compositions, gossiping about each other's infidelities and frolicking beneath the cherry boughs in the hills of Piedmont – Alex Kershaw, historian[37]Formed after 1898, they met at Xavier Martinez's home on Sundays, and at Jack London's home on Wednesdays.

London asked William Randolph Hearst, the owner of the San Francisco Examiner, to be allowed to transfer to the Imperial Russian Army, where he felt that restrictions on his reporting and his movements would be less severe.

Other noted members of the Bohemian Club during this time included Ambrose Bierce, Gelett Burgess, Allan Dunn, John Muir, Frank Norris,[citation needed] and Herman George Scheffauer.

The two met prior to his first marriage but became lovers years later after Jack and Bessie London visited Wake Robin, Netta Eames' Sonoma County resort, in 1903.

[58][59] Joseph Noel calls the events from 1903 to 1905 "a domestic drama that would have intrigued the pen of an Ibsen.... London's had comedy relief in it and a sort of easy-going romance.

Stasz writes that London "had taken fully to heart the vision, expressed in his agrarian fiction, of the land as the closest earthly version of Eden ... he educated himself through the study of agricultural manuals and scientific tomes.

In his autobiographical memoir John Barleycorn, he claims, as a youth, to have drunkenly stumbled overboard into the San Francisco Bay, "some maundering fancy of going out with the tide suddenly obsessed me.

[82] In July 1901, two pieces of fiction appeared within the same month: London's "Moon-Face", in the San Francisco Argonaut, and Frank Norris' "The Passing of Cock-eye Blacklock", in Century Magazine.

[99]London shared common concerns among many European Americans in California about Asian immigration, described as "the yellow peril"; he used the latter term as the title of a 1904 essay.

[103] On his fears about China, he admits (at the end of "The Yellow Peril"), "it must be taken into consideration that the above postulate is itself a product of Western race-egotism, urged by our belief in our own righteousness and fostered by a faith in ourselves which may be as erroneous as are most fond race fancies."

This character is based on Hawaiian leper Kaluaikoolau, who in 1893 revolted and resisted capture from forces of the Provisional Government of Hawaii in the Kalalau Valley.

[citation needed] Those who defend London against charges of racism cite the letter he wrote to the Japanese-American Commercial Weekly in 1913: In reply to yours of August 16, 1913.

[9] London advised his collaborator Anna Strunsky during preparation of The Kempton-Wace Letters that he would take the role of eugenics in mating, while she would argue on behalf of romantic love.

Falling through the ice into a creek in seventy-five-below weather, the unnamed man is keenly aware that survival depends on his untested skills at quickly building a fire to dry his clothes and warm his extremities.

After publishing a tame version of this story—with a sunny outcome—in The Youth's Companion in 1902, London offered a second, more severe take on the man's predicament in The Century Magazine in 1908.

As Labor (1994) observes: "To compare the two versions is itself an instructive lesson in what distinguished a great work of literary art from a good children's story.

"[B] Other stories from the Klondike period include: "All Gold Canyon", about a battle between a gold prospector and a claim jumper; "The Law of Life", about an aging American Indian man abandoned by his tribe and left to die; "Love of Life", about a trek by a prospector across the Canadian tundra; "To the Man on Trail," which tells the story of a prospector fleeing the Mounted Police in a sled race, and raises the question of the contrast between written law and morality; and "An Odyssey of the North," which raises questions of conditional morality, and paints a sympathetic portrait of a man of mixed White and Aleut ancestry.

[116] In a letter dated December 27, 1901, London's Macmillan publisher George Platt Brett, Sr., said "he believed Jack's fiction represented 'the very best kind of work' done in America.

"[citation needed] The historian Dale L. Walker[114] commented: Jack London was an uncomfortable novelist, that form too long for his natural impatience and the quickness of his mind.

[114] Ambrose Bierce said of The Sea-Wolf that "the great thing—and it is among the greatest of things—is that tremendous creation, Wolf Larsen ... the hewing out and setting up of such a figure is enough for a man to do in one lifetime."

[119] The words Shepard quoted were from a story in the San Francisco Bulletin, December 2, 1916, by journalist Ernest J. Hopkins, who visited the ranch just weeks before London's death.

[121] Part of the credo was used to describe the philosophy of the fictional character James Bond, in the Ian Fleming novel You Only Live Twice (1964), and again in the movie No Time to Die (2021).

[citation needed] This passage as given above was the subject of a 1974 Supreme Court case, Letter Carriers v. Austin,[129] in which Justice Thurgood Marshall referred to it as "a well-known piece of trade union literature, generally attributed to author Jack London".

The court ruled that "Jack London's... 'definition of a scab' is merely rhetorical hyperbole, a lusty and imaginative expression of the contempt felt by union members towards those who refuse to join", and as such was not libelous and was protected under the First Amendment.