1920 East Prussian plebiscite

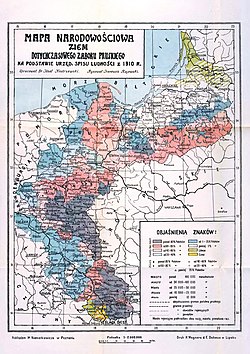

The area concerned had changed hands at various times over the centuries between the Old Prussians, the monastic state of the Teutonic Knights, the Duchy of Prussia, Germany and Poland.

The area of Warmia had been part of the Kingdom of Prussia since the first Partition of Poland in 1772, and the region of Masuria was ruled by the German Hohenzollern family since the Prussian Tribute of 1525, as a Polish fief until 1660.

[10] The Polish delegation at the Paris Peace Conference, led by Roman Dmowski, made a number of demands in relation to areas that had been part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth until 1772.

The plebiscite areas[12] (German: Abstimmungsgebiete; French: zones du plébiscite) were placed under the authority of two Inter-Allied Commissions of five members, who were appointed by the Principal Allied and Associated Powers representing the League of Nations.

British and Italian troops, under the command of the Commissions, arrived on and soon after 12 February 1920 after the regular German Reichswehr had previously left the plebiscite areas.

The German government, under the Protocol's terms, was allowed to attach a delegate and sent Reichskommissar Wilhelm von Gayl, who had been in the service of the Interior Ministry before he was on the Inner Colonisation Committee.

According to Jerzy Minakowski, the small forces had proven themselves inadequate to protect pro-Polish voters in the precincts from pro-German repressions.

[20] The Commission had general powers of administration and was particularly "charged with the duty of arranging for the vote and of taking such measures as it may deem necessary to ensure its freedom, fairness, and secrecy.

[23] The commission eventually had to remove both the mayor of Allenstein, Georg Zülch [de], and an officer of Sicherheitswehr, Major Oldenburg, after a Polish banner at the local consulate of Poland was defaced.

[26] The Allensteiner Zeitung newspaper called on its readers to remain calm and to cease pogroms against Poles and pointed out that they could lead to postponing the plebiscite, which would go against German interests.

[32] Sir Horace Rumbold, the British minister in Warsaw, also wrote to George Curzon on 5 March 1920 that the Plebiscite Commissions at Allenstein and Marienwerder "felt that they were isolated both from Poland and from Germany" and that the Polish authorities were holding up supplies of coal and petrol to those districts.

[34] The Poles began to harden their position, and Rumbold reported to Curzon on 22 March 1920 that Count Stefan Przeździecki [pl], an official of the Polish Foreign Office, had told Sir Percy Loraine, First Secretary at the legation at Warsaw, that the Poles questioned the impartiality of the Inter-Allied Commissions and indicated that the Polish government might refuse to recognise the results of the plebiscites.

In March 1919 Paul Hensel, the Lutheran Superintendent of Johannisburg, had travelled to Versailles to hand over a collection of 144,447 signatures to the Allies to protest the planned cession.

The pro-Germans presented the probability that all men would be drafted into the Polish military to fight Soviet Russia if they voted for the annexation by Poland.

The nationalist feelings were recently strengthened even more by the massive rebuilding programme of the devastated towns, which had been destroyed during the Russian invasion in the autumn of 1914 and were being financially adopted by large German cities.

They tried to convince the Masurians of Warmia (Ermland) and Masuria that they were victims of a long period of Germanisation but that the Poles now had the opportunity to liberate themselves from Prussian rule.

[43] Rennie reported to Curzon at the British Foreign Office on 18 February 1920 that the Poles, who had taken control of the Polish Corridor to the Baltic Sea, had "entirely disrupted the railway, telegraphic and telephone system, and the greatest difficulty is being experienced".

Rennie "pointed out to Dr. Lewandowski that he ought to realise that his position here was a delicate one... and I added it was highly desirable that his office should not be situated in a building with the Bureau of Polish propaganda".

He continued to note that "acts and articles violently abusive of everything German in the newly founded Polish newspaper appear to be the only (peaceful) methods adopted to persuade the inhabitants of the Plebiscite areas to vote for Poland".

Actions included murder, the most notable example being the killing of Bogumił Linka, a native Masurian member of the Polish delegation to Versailles, who supported voting for Poland.

However, the weight of that argument can not have been strong because the voters were aware East Prussia was just a German province, not a sovereign state, as an alternative for the Germany.

The activity of pro-German organisations and the Allied support for the participation of those who were born in the plebiscite area but did not live there any longer helped the vote toward Germany.

[60] Poland's supposed disadvantage by the Versailles Treaty stipulation was that it enabled those to return to vote if they were born in the plebiscite areas but no longer living there.

[citation needed] The organisation of the plebiscite was also influenced by Britain, which supported Germany out of fear of an increased power for France in postwar Europe.

[64][65][66][67][68] According to Jerzy Minakowski, terror and their unequal status made Poles boycott the preparations for the plebiscite, which allowed the Germans to add ineligible voters.

The strategic importance of the Prussian Eastern Railway line Danzig-Warsaw passing through the area of Soldau in the Neidenburg District [de] caused it to be transferred to Poland without a plebiscite; it was renamed Działdowo.