Eastern theater of the American Civil War

Following a Confederate attack on Washington, D.C., in 1864, Union forces commanded by Philip H. Sheridan launched a campaign in Shenandoah Valley, which cost the Confederacy control over a major food supply for Lee's army.

The eastern theater included the campaigns that are generally most famous in the history of the war, if not for their strategic significance, then for their proximity to the large population centers, major newspapers, and the capital cities of the opposing parties.

It has been argued that the western theater was more strategically important in defeating the Confederacy, but it is inconceivable that the civilian populations of both sides could have considered the war to be at an end without the resolution of Lee's surrender at Appomattox Courthouse in 1865.

The Union defeat at First Bull Run shocked the North, and a new sense of grim determination swept the United States as military and civilians alike realized that they would need to invest significant money and manpower to win a protracted, bloody war.

He was also strongly ambitious, and by November 1, he had maneuvered around Winfield Scott and was named general-in-chief of all the Union armies, despite the embarrassing defeat of an expedition he sent up the Potomac River at the Battle of Ball's Bluff in October.

[10] The remainder of operations on the North Carolina coast began in late 1864, with Benjamin Butler's and David D. Porter's failed attempt to capture Fort Fisher, which guarded the seaport of Wilmington.

Union forces at the Second Battle of Fort Fisher, led by Alfred H. Terry, Adelbert Ames, and Porter, in January 1865, were successful in defeating Gen. Braxton Bragg, and Wilmington fell in February.

Jackson, now reinforced to 17,000 men, decided to attack the Union forces individually rather than waiting for them to combine and overwhelm him, first concentrating on a column from the Mountain Department commanded by Robert Milroy.

Jackson attempted pursuit but was unsuccessful, due to looting by Ashby's cavalry and the exhaustion of his infantry; after a few days of rest, he followed Banks's forces as far as Harpers Ferry, where he skirmished with the Union garrison.

In a classic military campaign of surprise and maneuver, he pressed his army to travel 646 miles (1,040 km) in 48 days of marching and won five significant victories with a force of about 17,000 against combined foes of 60,000.

Although Lincoln favored the overland approach because it would shield Washington from any attack while the operation was in progress, McClellan argued that the road conditions in Virginia were intolerable, that he had arranged adequate defenses for the capital, and that Johnston would certainly follow him if he moved on Richmond.

And the U.S. Navy failed to assure McClellan that they could protect operations on either the James or the York, so his idea of amphibiously enveloping Yorktown was abandoned, and he ordered an advance up the Peninsula to begin April 4.

In particular, the division under John B. Magruder, who was an amateur actor before the war, was able to fool McClellan by ostentatiously marching small numbers of troops past the same position multiple times, appearing to be a larger force.

Pressured by Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his military advisor Robert E. Lee, Johnston decided to attack the smaller Union force south of the river, hoping that the flooded Chickahominy, swollen from recent heavy rains, would prevent McClellan from moving to the southern bank.

[23] Lee then moved onto the offensive, conducting a series of battles that lasted seven days (June 25 – July 1) and pushed McClellan back to a safe but nonthreatening position on the James River.

The attack was poorly coordinated, and the Union lines held for most of the day, but Lee eventually broke through and McClellan withdrew again, heading for a secure base at Harrison's Landing on the James River.

Although the Union corps commanders felt that they could hold the field against further Confederate attacks, the supply situation would have been problematic and McClellan ordered the army to retreat back to Harrison's Landing.

The Army of the Potomac withdrew to the safety of the James River, protected by fire from Union gunboats, and stayed there until August, when they were withdrawn by order of President Lincoln in the run-up to the Second Battle of Bull Run.

Lee's new plan in the face of all these additional forces outnumbering him was to send Jackson and Stuart with half of the army on a flanking march to cut Pope's line of communication, the Orange & Alexandria Railroad.

This surprise movement forced Pope to leave his defensive line along the Rappahannock and move toward Manassas Junction in the hopes of crushing Jackson's wing before the rest of Lee's army could reunite with it.

And he wished to lower Northern morale, believing that an invading army wreaking havoc inside the North might force Lincoln to negotiate an end to the war, particularly if he would be able to incite an uprising in the slave-holding state of Maryland.

Longstreet was sent to Hagerstown, while Jackson was ordered to seize the Union arsenal at Harpers Ferry, which commanded Lee's supply lines through the Shenandoah Valley; it was also a tempting target, virtually indefensible.

At the Battle of South Mountain on September 14, the Confederate defenders were driven back by the numerically superior Union forces, and McClellan was in a position to destroy Lee's army before it could concentrate.

Administrative difficulties prevented the pontoon bridging boats from arriving on time, and his army was forced to wait across the river from Fredericksburg while Lee took that opportunity to fortify a defensive line on the heights behind the city.

Hooker, who had an excellent record as a corps commander in previous campaigns, spent the remainder of the winter reorganizing and resupplying his army, paying special attention to health and morale issues.

However, after minor initial contact with the enemy, Hooker began to lose his confidence, and rather than striking the Army of Northern Virginia in its rear as planned, he withdrew to a defensive perimeter around Chancellorsville.

As they crossed the Potomac and entered Frederick, Maryland, the Confederates were spread out over a considerable distance in Pennsylvania, with Richard Ewell across the Susquehanna River from Harrisburg and James Longstreet and A. P. Hill behind the mountains in Chambersburg.

His cavalry, under Jeb Stuart, was engaged in a wide-ranging raid around the eastern flank of the Union army and was uncharacteristically out of touch with headquarters, leaving Lee blind as to his enemy's position and intentions.

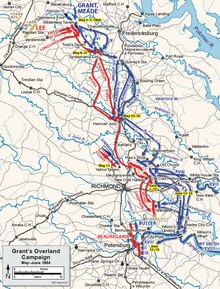

There, in dense woods that nullified the Union army's advantages in artillery as well as diminishing the impact of its almost two-to-one superiority in numbers, Robert E. Lee surprised Grant and Meade with aggressive assaults.

During the day and into the night, Lee pulled his forces out from Petersburg and Richmond and headed west to Danville, the destination of the fleeing Confederate government, and then south to meet up with General Joseph E. Johnston in North Carolina.