Economic equilibrium

[1] Market equilibrium in this case is a condition where a market price is established through competition such that the amount of goods or services sought by buyers is equal to the amount of goods or services produced by sellers.

Take a system where physical forces are balanced for instance.This economically interpreted means no further change ensues.

This will tend to put downward pressure on the price to make it return to equilibrium.

Even if it satisfies properties P1 and P2, the absence of P3 means that the market can only be in the unstable equilibrium if it starts off there.

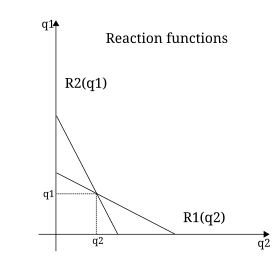

It is used whenever there is a strategic element to the behavior of agents and the "price taking" assumption of competitive equilibrium is inappropriate.

Cournot himself argued that it was stable using the stability concept implied by best response dynamics.

Most economists, for example Paul Samuelson,[6] caution against attaching a normative meaning (value judgement) to the equilibrium price.

Indeed, this occurred during the Great Famine in Ireland in 1845–52, where food was exported though people were starving, due to the greater profits in selling to the English – the equilibrium price of the Irish-British market for potatoes was above the price that Irish farmers could afford, and thus (among other reasons) they starved.

[7] In most interpretations, classical economists such as Adam Smith maintained that the free market would tend towards economic equilibrium through the price mechanism.

That is, any excess supply (market surplus or glut) would lead to price cuts, which decrease the quantity supplied (by reducing the incentive to produce and sell the product) and increase the quantity demanded (by offering consumers bargains), automatically abolishing the glut.

Similarly, in an unfettered market, any excess demand (or shortage) would lead to price increases, reducing the quantity demanded (as customers are priced out of the market) and increasing in the quantity supplied (as the incentive to produce and sell a product rises).

This automatic abolition of non-market-clearing situations distinguishes markets from central planning schemes, which often have a difficult time getting prices right and suffer from persistent shortages of goods and services.

In some ways parallel is the phenomenon of credit rationing, in which banks hold interest rates low to create an excess demand for loans, so they can pick and choose whom to lend to.

Further, economic equilibrium can correspond with monopoly, where the monopolistic firm maintains an artificial shortage to prop up prices and to maximize profits.

Finally, Keynesian macroeconomics points to underemployment equilibrium, where a surplus of labor (i.e., cyclical unemployment) co-exists for a long time with a shortage of aggregate demand.

In other words, prices where demand and supply are out of balance are termed points of disequilibrium, creating shortages and oversupply.

Consider the following demand and supply schedule: When there is a shortage in the market we see that, to correct this disequilibrium, the price of the good will be increased back to a price of $5.00, thus lessening the quantity demanded and increasing the quantity supplied thus that the market is in balance.

A decrease in disposable income would have the exact opposite effect on the market equilibrium.

This is another way of saying that the total derivative of price with respect to consumer income is greater than zero.

At the other extreme, many economists view labor markets as being in a state of disequilibrium—specifically one of excess supply—over extended periods of time.

- P – price

- Q – quantity demanded and supplied

- S – supply curve

- D – demand curve

- P 0 – equilibrium price

- A – excess demand – when P<P 0

- B – excess supply – when P>P 0