Economy of India under the British Raj

Ferguson argues that since the sector represented three quarters of the entire population, their rising share reduced income inequality in India.

At the same time, protectionist policies in Britain, such as bans and high tariffs, were implemented to restrict Indian textiles from being sold there.

This form of revenue generation was a departure from the practices deployed by Indian rulers in the past, who primarily raised funds through global and regional trade networks rather than through taxing farmers.

[6] However, P. J. Marshall argues that the British regime did not make any sharp breaks with the traditional economy, and that control was largely left in the hands of regional rulers.

The economy was sustained by general conditions of prosperity through the latter part of the 18th century, excepting the frequent famines with high fatality rates.

Marshall notes the British raised revenue through local tax administrators and kept the old Mughal rates of taxation.

India's per-capita income remained mostly stagnant during the Raj, with most of its GDP growth coming from an expanding population.

[6] India's GDP (PPP) per capita was stagnant during the Mughal Empire and began to decline prior to the onset of British rule.

India's GDP (PPP) per capita was stagnant during the Mughal Empire and began to decline prior to the onset of British rule.

[14] Due to the colonial policies of the British, a significant transfer of capital from India to England occurred, leading to a massive drain of revenue rather than a systematic effort at modernisation of the domestic economy.

[23] In the 17th century, India was a relatively urbanised and commercialised nation with a buoyant export trade devoted largely to cotton textiles, but also included silk, spices, and rice.

[7] As late as 1772, Henry Pattullo, writing about the economic resources of Bengal, commented that their textiles were of such unrivaled quality that demand for them could never wane.

[26] An oft repeated legend is that the EIC cut off the thumbs of weavers in Bengal to destroy the indigenous weaving industry in favour of British textile imports.

However, this is generally considered to be a myth originating from William Bolts' 1772 account, in which he alleges that a number of silk spinners had cut off their own thumbs in protest of poor working conditions.

[27][28] Economic historian Prasannan Parthasarathi pointed to earnings data that show real wages in 18th-century Bengal and Mysore were comparable to Britain.

In 1775, the British East India Company accepted the establishment of the Board of Ordnance at Fort William, Calcutta.

[37] The entrepreneur Jamsetji Tata began his industrial career in 1877 with the Central India Spinning, Weaving, and Manufacturing Company in Bombay.

[39] In the 1890s, Tata launched plans to expand into heavy industry using Indian funding after being denied permission by the British since 1883.

[41] According to The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, TISCO "became a symbol of Indian technical skill, managerial competence, and entrepreneurial flair".

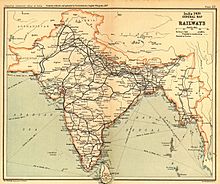

Historian David Gilmour says:[43] By the 1870s the peasantry in the districts irrigated by the Ganges Canal were visibly better fed, housed and dressed than before; by the end of the century the new network of canals in the Punjab had produced an even more prosperous peasantry there.British investors built a modern railway system in the late 19th century, which became the fourth largest in the world at the time.

[44] The government was supportive of the railways, realizing their value for military use and economic growth, and they were designed to improve defense and foreign trade.

From 1890, the year main stage construction was completed, to 1914, the proportion of overseas British capital invested in India declined from 19% to 10%.

[46] In 1854, Governor-General Lord Dalhousie formulated a plan to construct a network of trunk lines connecting the principal regions of India.

[47] In 1853, the first passenger train service was inaugurated between Bori Bunder in Bombay and Thane, covering a distance of 34 km (21 mi).

Several large princely states soon built their own rail systems, and the network spread to almost all the regions in India.

[46] By 1900, India had a full range of rail services with diverse ownership and management, operating on broad, meter, and narrow gauge networks.

[50] During World War I, railways were used to transport troops and grain to the ports of Bombay and Karachi en route to Britain, Mesopotamia, and East Africa.

Critical workers entered the army, workshops were converted to make munitions, and the locomotives, rolling stock, and track of some entire lines were shipped to the Middle East.

The government's Stores Policy required that bids on railway contracts be made to the India Office in London, shutting out most Indian firms.

In contrast, Nizam Asaf Jah VII of Hyderabad State in South India was widely reported to have a fortune of almost £668 million at that time.