Economy of the Qing dynasty

The High Qing era saw a period of rapid demographic and economic growth, followed by a near century of stagnation brought about by the unequal treaties, rebellions, floods, and a fiscally conservative and decentralised government.

[1][2] During this period the European trend to imitate Chinese artistic traditions, known as chinoiserie gained great popularity in Europe in the 18th century due to the rise in trade with China and the broader current of Orientalism.

This has therefore led to a great reliance on estimates of production and a reduction to general trends over specific numbers however the population largely remained close to 400,000,000 throughout the 1800s and early 1900s with a significant decrease during the mid-century era due to rebellions, floods, famines and other issues.

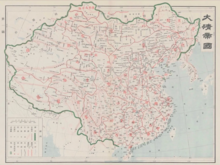

[4] The Qing dynasty controlled a large portion of Asia including areas beyond modern China, and so its agriculture was widely varied.

[6] Generally, the Qing Emperors discouraged the production of non-grain crops, believing them to be immoral and simultaneously causing food shortages.

This desire for modernisation was repeated by officials such as Zhang Zhidong, who noted that China already had issues of food supply and that the nation was overpopulated.

[8] Throughout the Qing period there was an immense increase in population, which placed an extraordinary pressure on the land to both provide work and feed the people.

These impressive units however disguise the fact that the vast majority of the 2.3 tons were the food for the farmers who grew it (who numbered far more than in other parts of the world), and little was left for the market.

This limited excess of food combined with a high demand for labour due to intensive agricultural methods meant that industrialisation was hindered and slowed.

Though there is no national data that exists in regard to this growth of cultivation, it was recorded that opium imports fell in quantity throughout the Late Qing period.

The coastal areas of Hubei, Shanxi and Zhili imported food from the rest of China and by the early 1800s the value of the domestic trade of foodstuffs was over 168,000,000 taels annually, an amount 3 times that of the grain tax.

Rather than surplus labour being applied to already-farmed plots and thereby boosting vertical productivity, untilled land became cleared and settled especially in the frontier regions.

[24] The Qing system of taxation was highly decentralised with the Throne assigning quotas for taxation on a local basis with the county or other government body providing the amount demanded by Beijing and keeping the rest for its own spending, the system of taxation was reliant overwhelmingly on the land and both its qualitative and quantitative value as well as a tax on registered male labourers per household, given the Qing did not register all land exchanges or movement of people this made the system reliant on frequent surveys which were carried out very rarely at a national level and infrequently at a local level leading to revenue struggling to keep pace with the growing expenses.

[26] The Qing system of government finance was extremely decentralised without any singular budget being published and taxes being allocated ad hoc this precludes any reliable collection of data and leads to discrepancies between sources therefore only estimates can be provided.

The government also inline with Confucian political thought at the time did little investment within the economy beyond what was viewed as strictly necessary such as providing for defense and internal order.

[27] The principal reason for this stagnation was the fixing of head tax rates by the Kangxi Emperor in 1712 which created a very inelastic revenue system which was very inflexible the Qing government had to devise workarounds to raise revenue, these included the meltage fee (a tax on appraisal of coinage) which was given to the officials as a way to combat corruption by accounting for their lack of pay.

[32][31] The Yongzheng emperor attempted to reign in corruption and malpractice regarding surcharges by a formalisation of the system where the meltage fee (huohao) depending on local circumstances became a formalised tax atop the land tax from 10 to 30% and was used to pay for the salaries of local officials and therefore prevent excessive surcharges which previously exceeded 30%.

[31] However, this did not prevent the additional surcharges as the primary reason for their existence was the absence of central government monitoring which was combatted through targeted auditing in corruption prone areas and the system worked.

[33] By the time of the Qianlong Emperor the rate of surcharges steadily increased once again and senior officials memorialised the throne appealing for the reversal of reforms as the surcharges were once again applied atop the meltage which was applied atop the poll tax which was applied atop the land tax thus leading to an overburdened populace despite these appeals the meltage fee remained in existence and as corruption rose as Qianlong's reign continued the rate of surcharges increased continually to the level that the Yongzheng saw necessary to implement reform.

[35] (shi)* (Early Kangxi) (Early Yongzheng) (Early Qianlong) (1766) (Mid Jiaqing) (1820) (Mid Daoguang) (1820) *A shi of grain fluctuated around 2 taels for the entire period within the table Entirely separate and alluded to in the previous formal taxation there was a large amount demnaded in informal taxation in the grain and land-poll tax, though little figures exist given the informal nature of these taxes the local governments collected an additional 50-60% demanded in formal taxation when averaged nationally as per the estimates of the provincial government themselves, thus the actual revenue was more akin to 50,000,000 taels annually and that of the grain tax being nearly 20,000,000 Shi.

This allowed the government to increase spending rapidly and to combat the mid-century rebellions as its basic fiscal system began to collapse.

This measure, first approved by Luo Bingzhang, was then rapidly applied in Hubei, Jiangxi, and Anhui, boosting their total revenues by up to 15%.

[38] However, unlike the era of Yongzheng, these measures were not repaid, as memorials to reverse the reforms were vigorously opposed by Liu Kunyi, who attacked the opposition.

There was no opposition from the throne and what little local opposition remained was overcome by the pressing demand for revenue brought about by rebellion eventually even the frontier regions of Xinjiang, Taiwan and Manchuria carried out surveys and official tillage increased by over 10% from 800,000,000 mu to 910,000,000 but given the local nature and weak Qing bureaucracy it is probable that the actual figure was in excess of this figure.

[48] Following the First Sino-Japanese war the financial burden on the Qing government was increased heavily as not only did it contract loans to pay for the war it additionally had to pay the large indemnity dictated by the Treaty of Shimonoseki, in the period of 1894-1898 the Qing government contracted a total of 350,457,485 taels in loans with varying interest rates (4.5%-7%).

These additional expenditures completely set aside the ramshackle balanced budget maintained by the Qing government until this point and the weight of interest payments and loan repayment necessitated a further increase in revenue.

Thus for the first time since the 1720s the formal agricultural tax was raised in gradual stages from 1901 to 1911 by 18,000,000 taels a large increase in a virtually stagnant form of taxation amounting to over 50%.