Economy of the Song dynasty

[6] Major irrigation projects included dredging the Yellow River at northern China and artificial silt land in the Lake Tai valley.

The wasteland plough was not made of iron, but of stronger steel, the blade was shorter but thicker, and particularly effective in cutting through reeds and roots in wetlands in the Huai River valley.

While there was already a great diversity in agricultural implements of the tread plow (tali 踏犁) because of lacking oxen, of lever-knife (zhadao 鍘刀) and the northeastern-style plow (tang 耥), the use of water power to move millstones, grinding stones and hammers and to move water from canals and rivers to irrigation ditches by a chained-buckets mechanism (fanche 翻車) became more and more usual, especially with large land owners.

In northern China, a "drill-tiller" (louchu 耬耡) was in use, while in the lower Yangtze region, a "plow-weeder" (tangyun 耥耘) became widespread at the end of Southern Song.

Cotton flowers were collected, pits removed, beaten loose with bamboo bows, drawn into yarns and weaved into cloth called "jibei".

[23] Rural families that sold a large agricultural surplus to the market not only could afford to buy more charcoal, tea, oil, and wine, but they could also amass enough funds to establish secondary means of production for generating more wealth.

[31][32] The pleasure district mentioned above—where stunts, games, theatrical stage performances, taverns and singing girl houses were located—was teeming with food stalls where business could be had virtually all night.

[30] Of the fifty some theatres within the pleasure districts of Kaifeng, four of these could entertain audiences of several thousand each, drawing huge crowds which would then give nearby businesses an enormous potential customer base.

[34] Besides food, traders in eagles and hawks, precious paintings, as well as shops selling bolts of silk and cloth, jewelry of pearls, jade, rhinoceros horn, gold and silver, hair ornaments, combs, caps, scarves, and aromatic incense thrived in the marketplaces.

[35] The arrangement of allowing competitive industry to flourish in some regions while setting up its opposite of strict government-regulated and monopolized production and trade in others was not exclusive to iron manufacturing.

[36] The reforms of the chancellor Wang Anshi (1021–1086) sparked heated debate amongst ministers of court when he nationalized the industries manufacturing, processing, and distributing tea, salt, and wine.

These seaports, now connected to the hinterland via canal, lake, and river traffic, acted as a string of large market centers for the sale of cash crops produced in the interior.

[43] The high demand in China for foreign luxury goods and spices coming from the East Indies facilitated the growth of Chinese maritime trade.

[45] Pearls, ivory, rhinoceros horns, frankincense, agalloch eaglewood, coral, agate, hawksbill turtle shell, gardenia, and rose were imported from the Arabs.

Hence, small groups of prominent families in any given local county would gain national spotlight for having sons travel far off to be educated and appointed as ministers of the state, but downward social mobility was always an issue with the matter of divided inheritance.

[60]: 68–69 From the late Tang to early Song period, Chinese craftsmen invented true porcelain in which the glaze, pigments and vessel body were all vitrified.

Porcelain and celadon replaced silk as China's main export during the Song period and kilns sprung up along coastal ports such as Quanzhou, where a Maritime Customs Superintendency was established in 1087.

The Quanzhou potters initially imitated Qingbai wares but had created their own distinctive styles by the 12th century that were popular in overseas markets such as Japan.

[64] Taking into account Wagner's reservations, the lowest estimates still put annual iron production levels at several times higher than the Tang dynasty.

[63] However, by the end of the 11th century the Chinese discovered that using bituminous coke could replace the role of charcoal, hence many acres of forested land in northern China were spared from the steel and iron industry with this switch of resources.

[42][63] Iron and steel of this period were used to mass-produce ploughs, hammers, needles, pins, nails for ships, musical cymbals, chains for suspension bridges, Buddhist statues, and other routine items for an indigenous mass market.

[73] This was done by roasting iron pyrites, converting the sulphide to oxide, as the ore was piled up with coal briquettes in an earthenware furnace with a type of still-head to send the sulfur over as vapour, after which it would solidify and crystallize.

[74][75] Even before this point, in 1067 AD, the Song government had issued an edict that the people living in Shanxi and Hebei were forbidden to sell foreigners any products containing saltpetre and sulfur.

[77] One of the main armories and arsenals for the storage of gunpowder and weapons was located at Weiyang, which accidentally caught fire and produced a massive explosion in 1280 AD.

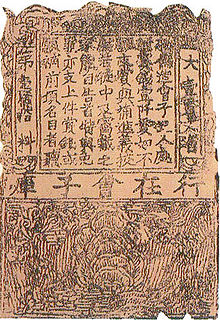

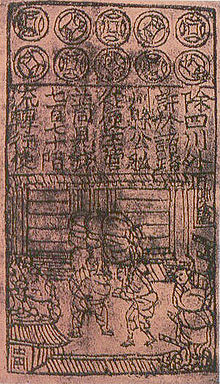

[78] The root of the development of the banknote goes back to the earlier Tang dynasty (618–907), when the government outlawed the use of bolts of silk as currency, which increased the use of copper coinage as money.

[49] With many 9th century Tang era merchants avoiding the weight and bulk of so many copper coins in each transaction, this led them to using trading receipts from deposit shops where goods or money were left previously.

[81] Merchants would deposit copper currency into the stores of wealthy families and prominent wholesalers, whereupon they would receive receipts that could be cashed in a number of nearby towns by accredited persons.

[82] Since the 10th century, the early Song government began issuing their own receipts of deposit, yet this was restricted mainly to their monopolized salt industry and trade.

[90] In that year of 1101, the Emperor Huizong of Song decided to lessen the amount of paper taken in the tribute quota, because it was causing detrimental effects and creating heavy burdens on the people of the region.

[82][92] The geographic limitation changed between the years 1265 and 1274, when the late Southern Song government finally produced a nationwide standard currency of paper money, once its widespread circulation was backed by gold or silver.