Ectotherm

[4] Some of these animals live in environments where temperatures are practically constant, as is typical of regions of the abyssal ocean and hence can be regarded as homeothermic ectotherms.

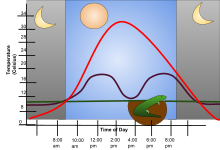

In contrast, in places where temperature varies so widely as to limit the physiological activities of other kinds of ectotherms, many species habitually seek out external sources of heat or shelter from heat; for example, many reptiles regulate their body temperature by basking in the sun, or seeking shade when necessary in addition to a host of other behavioral thermoregulation mechanisms.

In contrast to ectotherms, endotherms rely largely, even predominantly, on heat from internal metabolic processes, and mesotherms use an intermediate strategy.

To warm up, reptiles and many insects find sunny places and adopt positions that maximise their exposure; at harmfully high temperatures they seek shade or cooler water.

[citation needed] During periods of cold, some ectotherms enter a state of torpor, in which their metabolism slows or, in some cases, such as the wood frog, effectively stops.

[10] Ectotherms rely largely on external heat sources such as sunlight to achieve their optimal body temperature for various bodily activities.

In cool weather the foraging activity of such species is therefore restricted to the day time in most vertebrate ectotherms, and in cold climates most cannot survive at all.