Edgeworth box

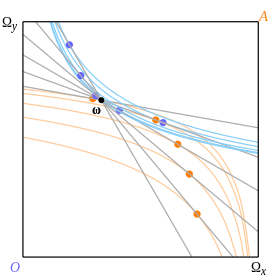

The top right-hand corner of the box represents the allocation in which Octavio holds all the goods, while the bottom left corresponds to complete ownership by Abby.

The main use of the Edgeworth box is to introduce topics in general equilibrium theory in a form in which properties can be visualised graphically.

[1] In the latter case, it serves as a precursor to the bargaining problem of game theory that allows a unique numerical solution.

[5] Edgeworth's original two-axis depiction was developed into the now familiar box diagram by Pareto in his 1906 Manual of Political Economy and was popularized in a later exposition by Bowley.

[6] The conceptual framework of equilibrium in a market economy was developed by Léon Walras[7] and further extended by Vilfredo Pareto.

[8] It was examined with close attention to generality and rigour by twentieth century mathematical economists including Abraham Wald,[9] Paul Samuelson,[10] Kenneth Arrow and Gérard Debreu.

[11] This was part of a wider movement in which Wald also sought to bring greater rigour to decision theory and many mathematicians concentrated on minimising dependence on the axiom of choice.

Areas in which premises can be strengthened or weakened include: Assumptions are also made of a more technical nature, e.g. non-reversibility, saturation, etc.

At first we will view them as convex and differentiable and concentrate on interior equilibria, but we will subsequently relax these assumptions.

Our aim is to find the price at which market equilibrium can be attained, which will be a point at which no further transactions are desired, starting from a given endowment.

This assumption requires a certain suspension of disbelief since the conditions for perfect competition – which include an infinite number of consumers – aren't satisfied.

Other authors who have a more game theoretical bent, such as Martin Osborne and Ariel Rubinstein,[13] use the term core for the section of the Pareto set which is at least as good for each consumer as the initial endowment.

[15] The restriction is that equilibrium implies that no local improvement can be made – in other words, that the point is 'locally' Pareto optimal.

[16] Thus if the nature of the indifference curves allows non-global optima to arise (as cannot happen if they are convex), then it is possible for equilibria not to be Pareto optimal.

Indeed, so long as the government recognises a desirable distribution of income it does not need to have any idea of the optimal allocation of resources.

In a statement for a more general economy, the theorem would be taken as saying that α' can be reached by a monetary transfer followed by the free play of market exchange; but money is absent from the Edgeworth box.

This preferred allocation is sometimes nowadays referred to as Octavio's 'demand', which constitutes an asymmetric description of a symmetric fact.

It might be supposed from economic considerations that if a shared tangent exists through a given endowment, and if the indifference curves are not pathological in their shape, then the point of tangency will be unique.

Kenneth Arrow and Gérard Debreu published papers independently in 1951 drawing attention to limitations in the calculus proofs of equilibrium theorems.

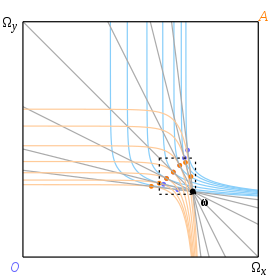

[21] Arrow specifically mentioned the difficulty caused by equilibria on the boundary, and Debreu the problem of non-differentiable indifference curves.

Without aiming for exhaustive coverage it is easy to see in intuitive terms how to extend our methods to apply to these cases.

12 there is an arc of legal price lines through a point of contact, each touching indifference curves without cutting them inside the box, and accordingly there is a range of possible equilibria for a given endowment.

They do however have a property which generalises the definition in terms of tangents, which is that the two curves can be locally separated by a straight line.

Arrow and Debreu defined equilibrium in the same way as each other in their (independent) papers of 1951 without providing any source or rationale for their definition.

[22] The new definition required a change of mathematical technique from the differential calculus to convex set theory.

Arrow and Debreu do not explain why they require global separation, which may have made their proofs easier but can be seen to have unexpected consequences.

Given that their definition does not include all equilibria which may exist when curves may be non-convex, it is possible that they meant the assumption of convexity in the former sense.

It has sometimes been found that results can be derived under their definition without assuming convexity in the proof (the first fundamental theorem of welfare economics being an example).

However the proof is no longer obvious, and the reader is referred to the article on Fundamental theorems of welfare economics.

Consequently the theorem needs either to be given convexity of preferences as a premise, or else to be stated in such a way that 'equilibrium' is not understood as 'competitive equilibrium' as defined above.