Perfect competition

Léon Walras[2] gave the first rigorous definition of perfect competition and derived some of its main results.

Joan Robinson and Edward Chamberlain came to many of the same conclusions regarding imperfect competition while still adding a bit of their twist to the theory.

Despite their similarities or disagreements about who discovered the idea, both were extremely helpful in allowing firms to understand better how to center their goods around the wants of the consumer to achieve the highest amount of revenue possible.

Those economists who believe in perfect competition as a useful approximation to real markets may classify those as ranging from close-to-perfect to very imperfect.

[4] In modern conditions, the theory of perfect competition has been modified from a quantitative assessment of competitors to a more natural atomic balance (equilibrium) in the market.

But if the principle of atomic balance operates in the market, then even between two equal forces perfect competition may arise.

If we try to artificially increase the number of competitors and to reduce honest local big business to small size, we will open the way for unscrupulous monopolies from outside.

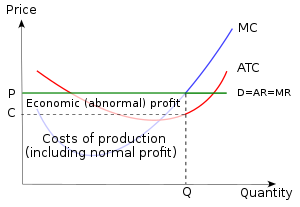

[11] In other words, the cost of normal profit varies both within and across industries; it is commensurate with the riskiness associated with each type of investment, as per the risk–return spectrum.

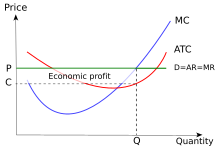

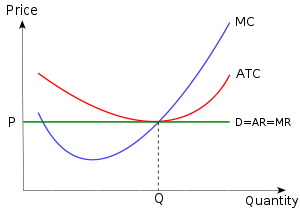

In circumstances of perfect competition, only normal profits arise when the long run economic equilibrium is reached; there is no incentive for firms to either enter or leave the industry.

[13][14][15] The same is likewise true of the long run equilibria of monopolistically competitive industries and, more generally, any market which is held to be contestable.

Normally, a firm that introduces a differentiated product can initially secure a temporary market power for a short while (See "Persistence" in Monopoly Profit).

Once risk is accounted for, long-lasting economic profit in a competitive market is thus viewed as the result of constant cost-cutting and performance improvement ahead of industry competitors, allowing costs to be below the market-set price.

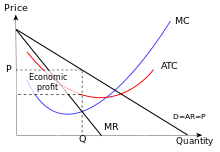

In these scenarios, individual firms have some element of market power: Though monopolists are constrained by consumer demand, they are not price takers, but instead either price-setters or quantity setters.

[13][16][17] However, some economists, for instance Steve Keen, a professor at the University of Western Sydney, argue that even an infinitesimal amount of market power can allow a firm to produce a profit and that the absence of economic profit in an industry, or even merely that some production occurs at a loss, in and of itself constitutes a barrier to entry.

In a single-goods case, a positive economic profit happens when the firm's average cost is less than the price of the product or service at the profit-maximizing output.

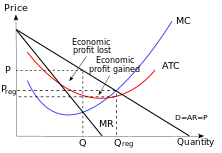

[14][15] For example, the old AT&T (regulated) monopoly, which existed before the courts ordered its breakup, had to get government approval to raise its prices.

In order not to misinterpret this zero-long-run-profits thesis, it must be remembered that the term 'profit' is used in different ways: Thus, if one leaves aside risk coverage for simplicity, the neoclassical zero-long-run-profit thesis would be re-expressed in classical parlance as profits coinciding with interest in the long period (i.e. the rate of profit tending to coincide with the rate of interest).

Laboratory experiments in which participants have significant price setting power and little or no information about their counterparts consistently produce efficient results given the proper trading institutions.

[23] The shutdown rule states "in the short run a firm should continue to operate if price exceeds average variable costs".

[24] Restated, the rule is that for a firm to continue producing in the short run it must earn sufficient revenue to cover its variable costs.

In the long run, the firm will have to earn sufficient revenue to cover all its expenses and must decide whether to continue in business or to leave the industry and pursue profits elsewhere.

[36] The use of the assumption of perfect competition as the foundation of price theory for product markets is often criticized as representing all agents as passive, thus removing the active attempts to increase one's welfare or profits by price undercutting, product design, advertising, innovation, activities that – the critics argue – characterize most industries and markets.

These criticisms point to the frequent lack of realism of the assumptions of product homogeneity and impossibility to differentiate it, but apart from this, the accusation of passivity appears correct only for short-period or very-short-period analyses, in long-period analyses the inability of price to diverge from the natural or long-period price is due to active reactions of entry or exit.

[40] In particular, the rejection of perfect competition does not generally entail the rejection of free competition as characterizing most product markets; indeed it has been argued[41] that competition is stronger nowadays than in 19th century capitalism, owing to the increasing capacity of big conglomerate firms to enter any industry: therefore the classical idea of a tendency toward a uniform rate of return on investment in all industries owing to free entry is even more valid today; and the reason why General Motors, Exxon or Nestlé do not enter the computers or pharmaceutical industries is not insurmountable barriers to entry but rather that the rate of return in the latter industries is already sufficiently in line with the average rate of return elsewhere as not to justify entry.

Thus when the issue is normal, or long-period, product prices, differences on the validity of the perfect competition assumption do not appear to imply important differences on the existence or not of a tendency of rates of return toward uniformity as long as entry is possible, and what is found fundamentally lacking in the perfect competition model is the absence of marketing expenses and innovation as causes of costs that do enter normal average cost.

Most non-neoclassical economists deny that a full flexibility of wages would ensure the full employment of labour and find a stickiness of wages an indispensable component of a market economy, without which the economy would lack the regularity and persistence indispensable to its smooth working.

Particularly radical is the view of the Sraffian school on this issue: the labour demand curve cannot be determined hence a level of wages ensuring the equality between supply and demand for labour does not exist, and economics should resume the viewpoint of the classical economists, according to whom competition in labour markets does not and cannot mean indefinite price flexibility as long as supply and demand are unequal, it only means a tendency to equality of wages for similar work, but the level of wages is necessarily determined by complex sociopolitical elements; custom, feelings of justice, informal allegiances to classes, as well as overt coalitions such as trade unions, far from being impediments to a smooth working of labour markets that would be able to determine wages even without these elements, are on the contrary indispensable because without them there would be no way to determine wages.

[43] As it is well known, requirements for a firm's cost-curve under perfect competition is for the slope to move upwards after a certain amount is produced.

This amount is small enough to leave a sufficiently large number of firms in the field (for any given total outputs in the industry) for the conditions of perfect competition to be preserved.

From a theoretical point of view, given the assumptions that there will be a tendency for continuous growth in size for firms, long-period static equilibrium alongside perfect competition may be incompatible.