Education in Mali

[4][16] Additionally, foreign policies, such as those in the United States and France, and community initiatives, such as the mobilization of animatrices, have developed Malian education.

[3] Many historians and authors, such as Charles Cutter, believe that Malians did not enjoy many rights during this era and faced an identity crisis while assimilating to French culture.

[19][7] These ethnic groups, along with many others in Mali, believed that sending children to these schools was a way to make a political and religious statement, acquire merit, and create an African-Muslim identity.

[17] Although this ordinance made major breakthroughs in the development of schools, historians such as Boniface Obichere cite it as being discriminatory against native Malians.

[6] These extra resources paired with lower amounts of government regulation allow these institutions to have smaller class sizes.

[6] After primary education, students can choose to continue upon their academic track and attend a lycée for three years which ends with an exam called the Baccalaureat.

[2] Conversely, Malian students can take a more pre-professional track and opt to attend a two or four year vocational program to obtain a technical degree.

[3] Increased spending on primary education, especially for children in rural areas and girls, has had the unintended effect of overtaxing the secondary school system.

The University includes five Faculties and two institutes: Islamic education began in the Malian religion as early as the 16th century, when Timbuktu had 150 Qur'anic schools.

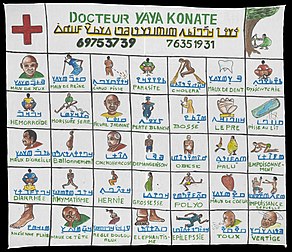

[19] Many Malians, especially those who reside in Bamako, Sikasso, and Kayes, attend madrassas, which are private Islamic schools that are mainly taught in Arabic for primary education.

[6] Similarly, many Malians attend informal Qur'anic schools which teach students how to read Arabic through using local languages.

[7] In the 1990s, the USAID, or United States Agency for International Development, created a community school program mainly for primary education in Mali.

[6] Community schools are taught in either French or local languages and provide students with technical, vocational, and literacy courses.

[8] In 1993, Bala Keita created the EDA or École pour les défients auditifs in Bamako which provides special education to deaf Malians.

[8] In the past three decades, Sikasso, Koutiala, Ségou, and Douentza saw an increase in schools for the deaf due to figures such as Dramane Diabaté and Dominique Pinsonneault.

[10] According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or UNESCO, 35.47% of Malians that are 15 years or older are able to read and write as of 2018.

[9] Although the government implemented literacy programs immediately after Mali gained independence, these initiatives became much more prominent during the democratic movements of the 1990s.

[10] Institutions such as the National Directorate of Functional Literacy and Applied Linguistics have been major proponents of providing adequate avenues for Malian neo-literates to practice their new skills.

[12] This initiative transformed classrooms into a source of learning about the various economic spheres of Mali and also allowed students to pursue their entrepreneurial goals.

[28][29] Additionally, many people, such as the researchers in this study, argue that students do not actually become literate through these programs due to inefficiencies in the implementation of literacy education.

[28][29] For example, in the four villages where the Puchner study took place, many Malians were illiterate mainly because they endured poor learning conditions and had few print resources to become educated.

[1] This law was passed right after Mali gained independence in an effort to improve the quality of Malian education and the accessibility of schooling.

[2] This was part of a larger effort to decolonize Mali post independence and shift the French-focused curriculum towards incorporating more information about Africa.

[2] This law introduced the Functional Literacy Program which provided education for adults who could not read or write in their local languages.

[17] Finally, in 1970, the government implemented the DEF, or Diploma d'Etudes Fondamental, which served as merit based exam to determine which students were able to transition to secondary and vocational schools following primary education.

[4] In a study about Gao, where animatrices are prominent, researchers found that the number of girls that attended schools nearly doubled in a three year span.

[4] Since 1987, Child Aid USA has been an organization that works to implement literacy programs for Malians and improve community education.

[29] Similarly, USAID, is an organization that provides aid to 9 regions of Mali to improve early literacy programs and community education.

[8] Although LSM utilizes local languages, which Malians are more familiar with, the United States supports ASL initiatives in Mali through working with the Peace Corps.

[33] This fund was incorporated into Mali in 2002 and has given Malians opportunities to obtain either a two year diploma or a Bachelor of Science in Agricultural Extension and Rural Development.