Education in Morocco

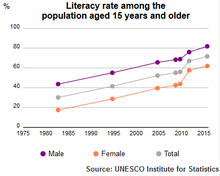

The government has launched several policy reviews to improve quality and access to education, and in particular to tackle a continuing problem of illiteracy.

[1][2] The Moroccan historian Mohamed Jabroun [ar] wrote that schools in Morocco were first built under the Almohad Caliphate (1121–1269).

[5] The Marinids founded a number of these schools,[6] including those in Fes, Meknes, and Salé, while the Saadis expanded the Ben Youssef Madrasa in Marrakesh.

[10] These boarding schools, which Susan Gilson Miller likens to Eton College, served to create Lyautey's vision for a class of bicultural Moroccan "gentlemen"—imbued with traditional ideals yet efficient in navigating modern bureaucratic systems—to fill roles in the country's administration.

"[11] It trained its Amazigh students for high roles in the colonial administration, as well as forming "a Berber elite steeped in French culture, in an environment where Arabic influences were rigorously excluded.

"[10][12] This hierarchical educational system was designed to "guarantee an indigenous elite loyal to France and ready to enter its service," though its permeability in practice made it a "vehicle of social mobility.

"[10] The inadequacies of traditional education at the msid became apparent, and private Moroccan citizens, particularly of the bourgeois merchant class, started to found what would later become known as "free schools"—with modernized curricula and instruction in Arabic—independently of each other.

[4] The teaching quality at these free schools varied greatly, from "uninspiring fqîhs, scarcely removed from their msîds" to "the country's most distinguished and imaginative 'ulamâ.

"[4] Many of the young teachers in Fes were simultaneously taking classes at al-Qarawiyyin University, and several would go on to lead the Moroccan Nationalist Movement.

[10] It was necessary to develop the educational system and a university network out of the limited resources left by the French in order to face the challenges awaiting the newly independent nation-state, such as "creating and consolidating state institutions, building a national economy, organizing civil society and the nascent political parties, [and] establishing social protections for a needy population.

[17][18] In 1958, Muhammad al-Fasi's successor, Abdelkarim Ben Jelloun [ar], established a blueprint for education reform in four goals: It was in 1963 that education was made compulsory for all Moroccan children between the ages of 6 through 13[19] and during this time all subjects were Arabized in the first and second grades, while French was maintained as the language of instruction of maths and science in both primary and secondary levels.

[24] In 1973, the humanities at government-controlled universities were Arabized, in which the Istiqlal leader Allal al-Fassi played a major role,[25] and curricula were substantially changed.

Arabization was instrumentalized to suppress critical thought,[24] a move which Dr. Susan Gilson Miller described as a "crude and obvious attempt to foster a more conservative atmosphere within academia and to dampen enthusiasm for the radicalizing influences filtering in from Europe.

"[26] The Minister of Education Azzeddine Laraki, following a report conducted by a committee of four Egyptians including two from al-Azhar University, replaced sociology with Islamic thought in 1983.

A 1973 article in Lamalif described Moroccan society as broken and fragmented, with misdirected energy from a discouraged and ashamed elite contributing to low standards of education.

In 1999, King Mohammed VI announced the National Charter for Education and Training (الميثاق الوطني للتربية و التكوين).

The World Bank and other multilateral agencies have helped Morocco to improve the basic education system.

Students are required to pass Certificat d'etudes primaires to be eligible for admission in lower secondary schools.

[38] The dropout rates have been falling since 2003, but is still very high compared to other Arab countries, such as Algeria, Oman, Egypt and Tunisia.

After 9 years of basic education, students begin upper secondary school and take a one-year common core curriculum, which is either in arts or science.

A number of universities have started providing software and hardware engineering courses as well; annually the academic sector produces 2,000 graduates in the field of information and communication technologies.

Private sector companies also do not make sufficient contribution in providing working knowledge to professional institutes of the current business environment.

There is also an unmet need of rising demand of middle schools after achieving high access rates in primary education.

The poor quality of education becomes an even greater problem due to Arabic-Berber language issues: most of the children from Berber families hardly know any Arabic, which is the medium of instruction in schools, when they enter primary level.

In this way Morocco is losing a substantial proportion of its skilled work force to foreign countries, forming the largest migrant population among North Africans in Europe.

In 2005 the Moroccan government adopted a strategy with the objective of making ICT accessible in all public schools to improve the quality of teaching; infrastructure, teacher training and the development of pedagogical content was also part of this national programme.

[46] In August 2019, the government passed a law to commence reforms on education including teaching science subjects in French language.

[55] A number of donors including USAID and UNICEF are implementing programs to improve the quality of education at the basic level and to provide training to teachers.

The World Bank also provides assistance in infrastructure upgrades for all levels of education and offer skill development trainings and integrated employment creation strategies to various stakeholders.

[36] At the request of the Government's highest authorities, a bold Education Emergency Plan (EEP) was drawn up to catch up on this reform process.