Education in early modern Scotland

By the early eighteenth century the network of parish schools was reasonably complete in the Lowlands, but limited in the Highlands where it was supplemented by the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge.

Scotland began to reap the benefits of its university system, with major early figures of the Enlightenment including Francis Hutcheson, Colin Maclaurin and David Hume.

In the Highlands there are indications of a system of Gaelic education associated with the professions of poetry and medicine, with ferleyn, who may have taught theology and arts, and rex scholarum of lesser status, but evidence of formal schooling is largely only preserved in place names.

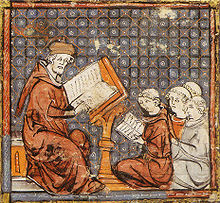

[5] From the end of the eleventh century universities had been founded across Europe, developing as semi-autonomous centres of learning, often teaching theology, mathematics, law and medicine.

This put an emphasis on classical authors, questioned some of the accepted certainties of established thinking and manifested itself in the teaching of new subjects, particularly through the medium of the Greek language.

They did not teach the Greek that was fundamental to the new Humanist scholarship, focusing on metaphysics, and putting a largely unquestioning faith in the works of Aristotle, whose authority would be challenged in the Renaissance.

[8] These international contacts helped integrate Scotland into a wider European scholarly world and would be one of the most important ways in which the new ideas of Humanism were brought into Scottish intellectual life.

[10] The civic values of humanism, which stressed the importance of order and morality, began to have a major impact on education and would become dominant in universities and schools by the end of the sixteenth century.

Reid was also instrumental in organising the public lectures that were established in Edinburgh in the 1540s on law, Greek, Latin and philosophy, under the patronage of the queen consort Mary of Guise.

It created a predominately Calvinist national church, known as the kirk, which was strongly Presbyterian in outlook, severely reducing the powers of bishops, although not initially abolishing them.

These were often informally created by parents in agreement with unlicensed schoolmasters, using available buildings and are chiefly evident in the historical record through complaints and attempts to suppress them by kirk sessions because they took pupils away from the official parish schools.

[19] Outside of the established burgh schools, which were generally better funded and more able to pay schoolmasters, masters often combined their position with other employment, particularly minor posts within the kirk, such as clerk.

A distinguished linguist, philosopher and poet, he had trained in Paris and studied law at Poitiers, before moving to Geneva and developing an interest in Protestant theology.

Influenced by the anti-Aristotelian Petrus Ramus, he placed an emphasis on simplified logic and elevated languages and sciences to the same status as philosophy, allowing accepted ideas in all areas to be challenged.

[24] From 1638 Scotland underwent a "second Reformation", with widespread support for a National Covenant, objecting to the Charles I's liturgical innovations and reaffirming the Calvinism and Presbyterianism of the kirk.

[24] By the late seventeenth century there was a largely complete network of parish schools in the Lowlands, but in the Highlands basic education was still lacking in many areas.

[27] Under the Commonwealth (1652–60), the universities saw an improvement in their funding, as they were given income from deaneries, defunct bishoprics and the excise, allowing the completion of buildings including the college in the High Street in Glasgow.

[29] The five Scottish universities recovered from the disruption of the civil war years and Restoration with a lecture-based curriculum that was able to embrace economics and science, offering a high-quality liberal education to the sons of the nobility and gentry.

[27] Historians now accept that very few boys were able to pursue this route to social advancement and that literacy was not noticeably higher than in comparable nations, as the education in the parish schools was basic and short and attendance was not compulsory.

[31] By the eighteenth century many poorer girls were being taught in dame schools, informally set up by a widow or spinster to teach reading, sewing and cooking.

[32] Among members of the aristocracy by the early eighteenth century a girl's education was expected to include basic literacy and numeracy, needlework, cookery and household management, while polite accomplishments and piety were also emphasised.

[38] Key figures in the Scottish Enlightenment who had made their mark before the mid-eighteenth century included Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746), who was professor of moral philosophy at Glasgow from 1729 to 1746.

Perhaps the most significant intellectual figure of early modern Scotland was David Hume (1711–76) whose Treatise on Human Nature (1738) and Essays, Moral and Political (1741) helped outline the parameters of philosophical Empiricism and Scepticism.