History of schools in Scotland

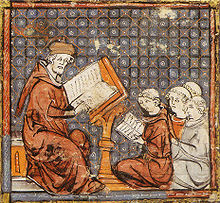

In the High Middle Ages, new sources of education arose including choir and grammar schools designed to train priests.

By the late seventeenth century there was a largely complete network of parish schools in the Lowlands, but in the Highlands basic education was still lacking in many areas.

Many poorer girls were being taught in dame schools, informally set up by a widow or spinster to teach reading, sewing and cooking.

Literacy rates were lower in the Highlands than in comparable Lowland rural society, and despite these efforts illiteracy remained prevalent into the nineteenth century.

From the early Middle Ages there were bardic schools, that trained individuals in the poetic and musical arts, but because Scotland was a largely oral society, little evidence of what they taught has survived.

[3] The new religious orders that became a major feature of Scottish monastic life in this period also brought new educational possibilities and the need to train larger numbers of monks.

Schools were supported by a combination of kirk funds, contributions from local heritors or burgh councils and parents that could pay.

These were often informally created by parents in agreement with unlicensed schoolmasters, using available buildings and are chiefly evident in the historical record through complaints and attempts to suppress them by kirk sessions because they took pupils away from the official parish schools.

[14] Outside of the established burgh schools, which were generally better funded and more able to pay schoolmasters, masters often combined their position with other employment, particularly minor posts within the kirk, such as clerk.

[13] Immediately after the Reformation they were in short supply, but there is evidence that the expansion of the university system provided large numbers of graduates by the seventeenth century.

[18] From 1638 Scotland underwent a "second Reformation", with widespread support for a National Covenant, objecting to the Charles I's liturgical innovations and reaffirming the Calvinism and Presbyterianism of the kirk.

[21] By the late seventeenth century there was a largely complete network of parish schools in the Lowlands, but in the Highlands basic education was still lacking in many areas.

Until the late eighteenth century most schools buildings were indistinguishable from houses, but the wealth from the Agricultural Revolution led to a programme of extensive rebuilding.

Many burgh schools moved away from this model of teaching from the late eighteenth century as the new commercial and vocational subjects led to the employment of more teachers.

[22] Historians now accept that very few boys were able to pursue this route to social advancement and that literacy was not noticeably higher than in comparable nations, as the education in the parish schools was basic and short and attendance was not compulsory.

[23] By the eighteenth century many poorer girls were being taught in dame schools, informally set up by a widow or spinster to teach reading, sewing and cooking.

[24] Among members of the aristocracy by the early eighteenth century a girl's education was expected to include basic literacy and numeracy, needlework, cookery and household management, while polite accomplishments and piety were also emphasised.

[27] Literacy rates were lower in the Highlands than in comparable Lowland rural society, and despite these efforts illiteracy remained prevalent into the nineteenth century.

[31] The influx of large numbers of Irish immigrants in the nineteenth century led to the establishment of Catholic schools, particularly in the urban west of the country, beginning with Glasgow in 1817.

The ideas were taken up in Aberdeen where Sheriff William Watson founded the House of Industry and Refuge, and they were championed by Scottish minister Thomas Guthrie who wrote Plea for Ragged Schools (1847), after which they rapidly spread across Britain.

[40] Ultimately Wood's ideas played a greater role in the Scottish educational system as they fitted with the need for rapid expansion and low costs that resulted from the reforms of 1872.

[38] Scottish schoolmasters gained a reputation for strictness and frequent use of the tawse, a belt of horse hide split at one end that inflicted stinging punishment on the hands of pupils.

[42] The Education Act 1861 removed the provision stating that Scottish teachers had to be members of the Church of Scotland or subscribe to the Westminster Confession.

The preferred method was to introduce vocational supplementary teaching in the elementary schools, later known as advanced divisions, up until the age of 14, when pupils would leave to find work.

[44] However, in the second half of the century roughly a quarter of university students can be described as having working class origins, largely from the skilled and independent sectors of the economy.

In 1890 school fees were abolished, creating a state-funded, national system of compulsory free basic education with common examinations.

The old academies and Higher Grade schools became senior secondaries, giving a more academic education, presenting students for the leaving certificate, which was the entry qualification for the universities.

[47] The Act also replaced the School Boards with 38 specialist local education authorities, which were elected by a form of proportional representation in order to protect the rights of the Catholic minority.

[44] Selection was ended by the Labour government in 1965, which recommended that councils produced one kind of comprehensive secondary school that took all the children in a given neighbourhood.

There was no distinctive Scottish style of school building in this period and patterns reflected those used in England, tending to be more open in plan and less rigid in design.