Education in the Philippines during Spanish rule

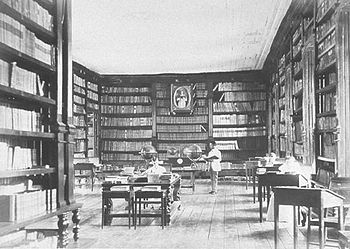

The oldest universities, colleges, and vocational schools, dating as far back as the late 16th century were created during the colonial period, as well as the first modern public education system in Asia, established in 1863.

By the time Spain was replaced by the United States as the colonial power, Filipinos were among the most educated peoples in all of Asia and the Pacific, boasting one of the highest literacy rates in that continent.

The Franciscans arrived in 1577, and they, too, immediately taught the people how to read and write, besides imparting to them important industrial and agricultural techniques.

[3] Within months of their arrival in Tigbauan which is in Iloilo province located in the island of Panay, Pedro Chirino and Francisco de Martín had established a school for Visayan boys in 1593 in which they taught not only the catechism but reading, writing, Spanish, and liturgical music.

By the end of the 16th century, several religious orders had established charity hospitals all over the archipelago and provided the bulk of this public service.

These hospitals also became the setting for rudimentary scientific research work on pharmacy and medicine, focusing mostly on the problems of infectious tropical diseases.

All of them provided courses leading to different prestigious degrees, like the Bachiller en Artes, that by the 19th century included science subjects such as physics, chemistry, natural history and mathematics.

By the end of the Spanish colonial rule in 1898. the university had granted the degree of Licenciado en Medicina to 359 graduates and 108 medical doctors.

For the doctorate degree in medicine its provision was inspired in the same set of oppositions than those of universities in the metropolis, and at least an additional year of study was required at the Universidad Central de Madrid in Spain.

In 1935 the Commonwealth government of the Philippines through the Historical Research and Markers Committee declared that UST was "oldest university under the American flag.

In 2010, the National Historical Commission of the Philippines installed a bronze marker declaring USC's foundation late in the 18th century, effectively disproving any direct connection with the Colegio de San Ildefonso.

[19] A Nautical School was created on January 1, 1820, which offered a four-year course of study (for the profession of pilot of merchant marine) that included subjects such as arithmetic, algebra, geometry, trigonometry, physics, hydrography, meteorology, navigation and pilotage.

The Don Honorio Ventura College of Arts and Trades (DHVCAT) in Bacolor, Pampanga is said to be the oldest official vocational school in Asia.

Throughout the nineteenth century the society established an academy of design, financed the publication of scientific and technical literature, and granted awards to successful experiments and inventions that improved agriculture and industry.

The Spanish government made the observatory the official institution for weather forecasting in the Philippines in 1884, and in 1885 it started its time service.

[2] The royal decree provided for a complete educational system consisting of primary, secondary and tertiary levels, resulting in valuable training for all Filipino children and youth.

[36] The Education Decree of 1863 provided for the establishment of at least two free primary schools, one for boys and another for girls, in each town under the responsibility of the municipal government.

[38] The range of subjects being taught were very advanced, as can be seen from the Syllabus of Education in the Municipal Atheneum of Manila, that included Algebra, Agriculture, Arithmetic, Chemistry, Commerce, English, French, Geography, Geometry, Greek, History, Latin, Mechanics, Natural History, Painting, philosophy, Physics, Rhetoric and poetry, Spanish Classics, Spanish Composition, Topography, and Trigonometry.

[11] Contrary to what the Propaganda of the Spanish–American War tried to depict, the Spanish public system of education was open to all the natives, regardless of race, gender or financial resources.

[42][43] Gunnar Myrdal, a renowned Swedish economist, observed that in 19th-century Asia, Japan and Spanish Philippines stood out because of their stress on modern public education.

This new enlightened class of Filipinos would later lead the Philippine independence movement, using the Spanish language as their main communication method.

Perhaps the best testimony for this is the fact that such larger numbers of Filipino students were able to move without apparent difficulty from educational institutions at home to those in the Peninsula and establish honorable records for themselves there.

[34] Ironically, it was during the time of American occupation of the Philippines that the results of Spanish education were more visible, especially in the literature, printed press and cinema.

[46] On November 30, 1900, the Philippine Commission reported to the US War Department about the state of education throughout the archipelago as follows: ...Under Spanish rule there were established in these islands a system of primary schools.

One observes in the schools a tendency on the part of the pupils to give back, like phonographs, what they have heard or read or memorized, without seeming to have thought for themselves.

The Spanish minister for the colonies, in a report made December 5, 1870, points out that, by the process of absorption, matters of education had become concentrated in the hands of the religious orders.

He says: "While every acknowledgement should be made of their services in earlier times, their narrow, exclusively religious system of education, and their imperviousness to modern or external ideas and influences, which every day become more and more evident, rendered secularization of instruction necessary."

However that assumption was misleading because it is calculated based on the entire population, including babies and senior citizens, when in reality public school systems are meant primarily for children and teenagers.

Another claim commonly heard was that based on the official figures there couldn't be a school in every village in the Islands, as Manuel L. Quezon declared years later before the Philippine Assembly.

Neither was taken into account that the schools maintained by Spain were closed and in many cases looted and badly damaged during the Spanish–American War and the Philippine Revolution.