Spanish language in the Philippines

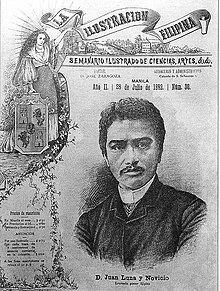

With the establishment of a free public education system set up by the viceroyalty government in the mid-19th century, a class of native Spanish-speaking intellectuals called the Ilustrados was formed, which included historical figures such as José Rizal, Antonio Luna and Marcelo del Pilar.

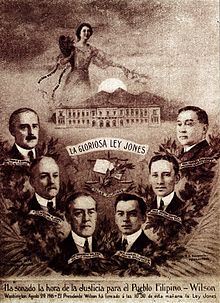

[3] It served as the country's first official language as proclaimed in the Malolos Constitution of the First Philippine Republic in 1899 and continued to be widely used during the first few decades of U.S. rule (1898–1946).

Today, the language is no longer present in daily life and despite interest in some circles to learn or revive it, it continues to see dwindling numbers of speakers and influence.

[3] During the early part of the U.S. administration of the Philippine Islands, Spanish was widely spoken and relatively well maintained throughout the American colonial period.

Pasyon is a narrative of the passion, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ begun by Gaspar Aquino de Belén, which has circulated in many versions.

Unlike the missionary's grammar, which Pinpin had set in type, the Tagalog native's book dealt with the language of the dominant, rather than the subordinate, other.

As such, it is richly instructive for what it tells us about the interests that animated Tagalog translation and, by implication, conversion during the early colonial period.

By the end of the 19th century, Spanish was either a mother tongue or a strong second language among the educated elite of the Philippine society, having been learned in childhood either directly from parents and grandparents or in school, or through tutoring.

[33] With the small period of the spread of Spanish through a free public school system (1863) and the rise of an educated class, nationalists from different parts of the archipelago were able to communicate in a common language.

José Rizal's novels, Graciano López Jaena's satirical articles, Marcelo H. del Pilar's anti-clerical manifestos, the bi-weekly La Solidaridad, which was published in Spain, and other materials in awakening nationalism were written in Spanish.

[34][35][36] Even Graciano López Jaena's La Solidaridad, an 1889 article that praised the young women of Malolos who petitioned to Governor-General Valeriano Weyler to open a night school to teach the Spanish language.

Highly instrumental in developing nationalism were his novels, Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo which exposed the abuses of the colonial government and clergy, composed of "Peninsulares."

According to the historian James B. Goodno, author of the Philippines: Land of Broken Promises (New York, 1998), one-sixth of the total population of Filipinos, or about 1.5 million, died as a direct result of the war.

Greater percentage of Spanish-speaking males compared to their English-speaking counterparts were found in Zamboanga, Manila, Isabela, Cotabato, Marinduque, Cagayan, Iloilo, Cavite, Albay, Leyte, Batangas, and Sorsogon.

The province with the greater percentage of Spanish-speaking females compared to their English-speaking counterparts were found in Zamboanga, Cotabato, Manila, Davao, Ambos Camarines, Iloilo, and Sorsogon.

[48]: 47 He also made note of the increasing usage of the native vernacular languages through which the literature of Filipino politics reached the masses, with the native newspapers and magazines in the Philippines tending to be bilingual and with the regular form being a Spanish section and a section written in the local vernacular language, while none of them was published in English.

It was then re-established by Martín Ocampo in 1910 under the name of La Vanguardia, although it did not prosper until its purchase in 1916 by Alejandro Roces, after which it continued publishing until the days of World War II.

Another important newspaper was El Ideal, which was established in 1910 and served as an official organ of the Nationalist Party created by Sergio Osmeña, although it was allowed to die in 1916 due to financial reasons.

[49][50][51] After the Silver Age came the period of decadence of the Philippine press written in Spanish, which Checa Godoy identified in the years of the 1920s and the 1930s.

[46]: 370 Inés Villa, the 1932 Premio Zobel awardee, wrote in her prize-winning work "Filipinas en el camino de la cultura" that the educational system during the American period succeeded in its objective of widely disseminating the English language and making it an official language of the government, legislature, courts, commerce and private life, adding that the United States managed to achieve with English for only three decades what Spain failed to achieve with the Spanish language during its approximately four centuries of rule in the Philippines, further noting that as of the writing of her work, for every Filipino that speaks Spanish, there are approximately ten others that can speak English.

[54]: 325 The years of the American colonial period have been identified as the Golden Age of Philippine Literature in Spanish by numerous scholars such as Estanislao Alinea, Luis Mariñas and Lourdes Brillantes.

Among the great Filipino literary writers of the period were Fernando María Guerrero, Jesús Balmori, Manuel Bernabé, Claro M. Recto and Antonio Abad.

[55][56] Additionally, despite the relevance given to many of these writers in their social and nationalistic roles, even earning them an entry in the 1996 Encyclopedia of the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP), most of their literary works received scarce public reception even during their lifetime.

However, it soon declined afterwards as the U.S. administration began a heavier imposition of English as the official language and medium of instruction in schools and universities.

Despite the fact that in 1934 it was established that American sovereignty would cease in 1946, the new Philippine Constitution stated the obligation to maintain English as the sole language of instruction.

[60] Those ideas gradually inculcated into the minds of the young generation of Filipinos (during and after the U.S. administration), which used those history textbooks at school that tended to generalize all Spaniards as villains because of lack of emphasis on Filipino people of Spanish ancestry, who were also against the local Spanish government and clergy and also fought and died for the sake of freedom during the 19th-century revolts during the Philippine Revolution, the Philippine–American War, and the Second World War.

[1] The 21st century has seen a small revival of interest in the language among select circles, with the numbers of those studying it formally at college or taking private courses rising markedly in recent years.

[71] Some Hispanista groups have even proposed making Spanish a compulsory subject again in school or having it used in administration, although the idea has elicited controversy among non-Spanish-speaking Filipinos.

[78] After Spain handed over control of the Philippines to the United States in 1898, the local variety of Spanish has lost most of its speakers, and it might be now close to disappearing.

Also, Filipinas, Ahora Mismo was a nationally syndicated, 60-minute, cultural radio magazine program in the Philippines that was broadcast daily in Spanish for two years in the 2000s.