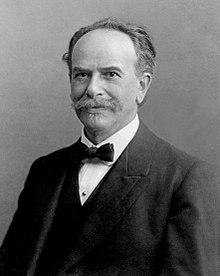

Edward Sapir

Edward Sapir (/səˈpɪər/; January 26, 1884 – February 4, 1939) was an American anthropologist-linguist, who is widely considered to be one of the most important figures in the development of the discipline of linguistics in the United States.

He studied Germanic linguistics at Columbia, where he came under the influence of Franz Boas, who inspired him to work on Native American languages.

He was employed by the Geological Survey of Canada for fifteen years, where he came into his own as one of the most significant linguists in North America, the other being Leonard Bloomfield.

In the 1929 edition of Encyclopædia Britannica he published what was then the most authoritative classification of Native American languages, and the first based on evidence from modern comparative linguistics.

His father had difficulty keeping a job in a synagogue and finally settled in New York on the Lower East Side, where the family lived in poverty.

After settling in New York, Edward Sapir was raised mostly by his mother, who stressed the importance of education for upward social mobility, and turned the family increasingly away from Judaism.

Through Germanics professor William Carpenter, Sapir was exposed to methods of comparative linguistics that were being developed into a more scientific framework than the traditional philological approach.

He also enrolled in an advanced anthropology seminar taught by Franz Boas, a course that would completely change the direction of his career.

Having finished his coursework, Sapir moved on to his doctoral fieldwork, spending several years in short-term appointments while working on his dissertation.

This first experience with Native American languages in the field was closely overseen by Boas, who was particularly interested in having Sapir gather ethnological information for the Bureau.

Sapir gathered a volume of Wishram texts, published 1909, and he managed to achieve a much more sophisticated understanding of the Chinook sound system than Boas.

In the end Sapir didn't finish the work during the allotted year, and Kroeber was unable to offer him a longer appointment.

[14] Sapir ended up leaving California early to take up a fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania, where he taught Ethnology and American Linguistics.

His "Grammar of Southern Paiute" was supposed to be published in Boas' Handbook of American Indian Languages, and Boas urged him to complete a preliminary version while funding for the publication remained available, but Sapir did not want to compromise on quality, and in the end the Handbook had to go to press without Sapir's piece.

Boas kept working to secure a stable appointment for his student, and by his recommendation Sapir ended up being hired by the Canadian Geological Survey, who wanted him to lead the institutionalization of anthropology in Canada.

He brought his parents with him to Ottawa, and also quickly established his own family, marrying Florence Delson, who also had Lithuanian Jewish roots.

Sapir insisted that the discipline of linguistics was of integral importance for ethnographic description, arguing that just as nobody would dream of discussing the history of the Catholic Church without knowing Latin or study German folksongs without knowing German, so it made little sense to approach the study of Indigenous folklore without knowledge of the indigenous languages.

By introducing the high standards of Boasian anthropology, Sapir incited antagonism from those amateur ethnologists who felt that they had contributed important work.

Unsatisfied with efforts by amateur and governmental anthropologists, Sapir worked to introduce an academic program of anthropology at one of the major universities, in order to professionalize the discipline.

[21] Sapir enlisted the assistance of fellow Boasians: Frank Speck, Paul Radin and Alexander Goldenweiser, who with Barbeau worked on the peoples of the Eastern Woodlands: the Ojibwa, the Iroquois, the Huron and the Wyandot.

Ishi died of his illness in early 1916, and Kroeber partly blamed the exacting nature of working with Sapir for his failure to recover.

[24] The First World War took its toll on the Canadian Geological Survey, cutting funding for anthropology and making the academic climate less agreeable.

Sapir's parents had by now divorced and his father seemed to develop psychosis, which made it necessary for him to leave Canada for Philadelphia, where Edward continued to support him financially.

Florence was hospitalized for long periods both for her depressions and for the lung abscess, and she died in 1924 due to an infection following surgery, providing the final incentive for Sapir to leave Canada.

He also participated in the formulation of a report to the American Anthropological Association regarding the standardization of orthographic principles for writing Indigenous languages.

Sapir also exerted influence through his membership in the Chicago School of Sociology, and his friendship with psychologist Harry Stack Sullivan.

He was invited to Yale to found an interdisciplinary program combining anthropology, linguistics and psychology, aimed at studying "the impact of culture on personality".

[32] At Yale, Sapir's graduate students included Morris Swadesh, Benjamin Lee Whorf, Mary Haas, Charles Hockett, and Harry Hoijer, several of whom he brought with him from Chicago.

"[43] Sapir also studied the languages and cultures of Wishram Chinook, Navajo, Nootka, Colorado River Numic, Takelma, and Yana.

His research on Southern Paiute, in collaboration with consultant Tony Tillohash, led to a 1933 article which would become influential in the characterization of the phoneme.