Edwardine Ordinals

[5]: 713 They also formed the basis for both the Vestiarian Controversy and, much later, some of the debate over the validity of Anglican holy orders and the subsequent 1896 papal bull Apostolicae curae where they were declared "absolutely null and utterly void" by the Catholic Church.

[9]: 263 Medieval pontificals gradually included and emphasized the conferral of the vestments and other items associated with their new offices, among these being stoles, patens, and chalices, in a custom known as the "tradition of elements" (Latin: traditio instrumentorum).

[14]: 529 With the English Reformation and independence of the Church of England from Rome, Henry VIII mandated that the oath of obedience to the pope be deleted from the Sarum and Roman pontificals still in use; these modifications can be seen in some preserved copies of these texts.

[11]: 786 [3]: cxxxi Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury and liturgist behind the 1549 prayer book, would perform an ordination with Nicholas Ridley, the Bishop of London and Westminster, at St Paul's Cathedral in 1549 according to the ritual soon to be legally requested.

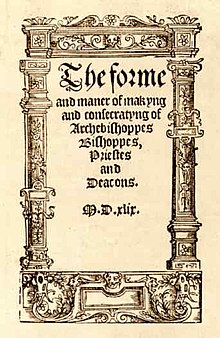

[7]: 8 [19]: x [14]: 528 The authorized ordinal was printed by Richard Grafton, bound separately from the prayer book, under the full name A forme and maner of makyng and consecratyng of Archebisshopes, Bisshopes, Priestes and Deacons.

As such, the 1550 ordinal was largely a simplification of those rituals with an intent to emphasize the imposition of hands and associate prayers, including the ancient hymn Veni Creator Spiritus.

According to the ordinal's preface, this was based on an interpretation of Scripture and ancient tradition that established a "existence of the threefold ministry" during the Apostolic age.

[23]: 82 The ordering and contents of the 1550 form for consecrating bishops differed from both that present in the Sarum Pontifical and Bucer's Latin liturgy:[3]: cxl Resistance to the first ordinal was not exclusive to the Catholic party.

"Priest" was considered too "popish" by some English clergy and laity and by the late 16th century many would independently adopt "minister" as their preferred word for the station.

[5]: 713 With the death of Edward VI in July 1553 at age 15, the Catholic Mary I ascended to throne and initiated the Marian Persecutions against the English Reformers.

Episcopal registers report that certain clergy ordained according to Edwardine Ordinals' forms were reordained during the Marian period, but do not record the reason.

[32]: 71 Following Elizabeth I assuming the throne and the Elizabethan Religious Settlement's return of Reformation values, the 1552 ordinal that had accompanied the 1552 prayer book was thought to have been authorized under the 1559 Act of Uniformity.

[34] The ordinal published in 1559 was essentially identical to that of 1552, but altered the wording of the oath from the "King's Supremacy" to the "Queen's Sovereignty" and removed reference to the pope's "usurped power and authority".

[32]: 38–40 This tension meant the religious situation of the Elizabethan period saw a significant degree of nonconformism and associated tendencies towards Presbyterianism alongside Catholic recusancy.

[20]: 56 John Whitgift became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1583 and, despite his Calvinist deferences, supported the "orthodoxy" of the Church of England in its view priesthood as a sacred office as defined in the Book of Common Prayer and the ordinal's ritual for ordaining priests and consecrating bishops.

[11]: 786 In 1909, a resolution was raised at the Church of England's convocation in the Committee of the Lower House of Canterbury to alter a portion of the ordination of deacons which had remained unchanged since 1550.

[32]: 158–159 Following the Anglican Church of Australia's adoption of An Australian Prayer Book in 1978 and the introduction of the ordination of women, longtime Moore Theological College principal Broughton Knox fostered a movement in Sydney that saw deference towards the 1552 conceptualization of the priesthood.

Catholic critics have argued that since Mary I's reign Anglican orders according to the Edwardine Ordinals have been seen as invalid, citing a 1554 injunction; the merits of this conclusion have been disputed by Bradshaw.

French Catholic Pierre François le Courayer, writing after moving to England, took an opposing position and cited that the Edwardine form was similar in substance to the Roman Pontifical.

[39]: 145 In 1852, Daniel Rock wrote approvingly of the 1704 decree and considered it still applicable in response to an American Episcopal Church bishop, Levi Silliman Ives, traveling to Rome to convert to Catholicism.

[41] Frederick Temple and William Maclagan–the Archbishops of Canterbury and York respectively–sent a response in 1897, Saepius officio, addressing the criticisms and arguments made in Apostolicae curae.

Raynal, writing in 1871, had commented on similar objections and claimed that even shorter Eastern Catholic ordination liturgies such as that of the Maronite Church were "brief but sufficient.

Unlike the 1552 ordinal's form, which Catholic authorities held were "definitively and unambiguously heretical", the preface was "ambiguous" on certain matters of doctrine, namely that of the Eucharist.