Effects of climate change on livestock

[6][7] This causes both mass animal mortality during heatwaves, and the sublethal impacts, such as lower quantity of quality of products like milk, greater vulnerability to conditions like lameness or even impaired reproduction.

[3] While some areas which currently support livestock animals are expected to avoid "extreme heat stress" even with high warming at the end of the century, others may stop being suitable as early as midcentury.

[3]: 750 In general, sub-Saharan Africa is considered to be the most vulnerable region to food security shocks caused by the impacts of climate change on their livestock, as over 180 million people across those nations are expected to see significant declines in suitability of their rangelands around midcentury.

[3]: 747 Much like how climate change is expected to increase overall thermal comfort for humans living in the colder regions of the world,[6] livestock in those places would also benefit from warmer winters.

[2] Across the entire world, however, increasing summertime temperatures as well as more frequent and intense heatwaves will have clearly negative effects, substantially elevating the risk of livestock suffering from heat stress.

Under the climate change scenario of highest emissions and greatest warming, SSP5-8.5, "cattle,sheep, goats, pigs and poultry in the low latitudes will face 72–136 additional days per year of extreme stress from high heat and humidity".

Historically, livestock in these conditions were considered less vulnerable to warming than the animals in outdoor areas due to inhabiting insulated buildings, where ventilation systems are used to control the climate and relieve the excess heat.

[19] In the United States alone, economic losses caused by heat stress in livestock were already valued at between $1.69 and $2.36 billion in 2003, with the spread reflecting different assumptions about the effectiveness of contemporary adaptation measures.

[3]: 748 A range of climate change adaptation measures can help to protect livestock, such as increasing access to drinking water, creating better shelters for animals kept outdoors and improving air circulation in the existing indoor facilities.

[23] Insufficient supply or quality of either leads to a decrease in growth and reproductive efficiency in domestic animals, especially in conjunction with the other stressors, and at worst, may increase mortality due to starvation.

Consequently, Iranian rangelands support over twice their sustainable capacity, and this leads to mass mortality in poor years, such as when around 800,000 goats and sheep in Iran perished due to the severe 1999 − 2001 drought.

96% of overall forage growth on such prairies stems from just six plant species, and they become 38% more productive largely in response to the increased CO2 levels, yet their nutritious value to livestock also declines by 13% due to the same, as they grow less edible tissue and become harder to digest.

[39] Similar response was observed in Stylosanthes capilata, another important forage species in the tropics, which is likely to become more prevalent with warming, yet which may require irrigation to avoid substantial losses in nutritional value.

[3]: 748 Similarly, an older study found that if 1.1 °C (2.0 °F) of warming occurs between 2005 and 2045 (rate comparable to hitting 2 °C (3.6 °F) by 2050), then under the current livestock management paradigm, global agricultural costs would increase by 3% (an estimated $145 billion), with the impact concentrated in pure pasturalist systems.

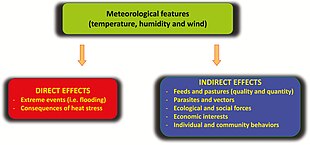

[42] While climate-induced heat stress can directly reduce domestic animals' immunity against all diseases,[2] climatic factors also impact the distribution of many livestock pathogens themselves.

[14] Without a significant improvement in epidemiological control measures, what is currently considered an once-in-20-years outbreak of bluetongue would occur as frequently as once in five or seven years by midcentury under all but the most optimistic warming scenario.

[3]: 747 Ixodes ricinus, a tick which spreads pathogens like Lyme disease and tick-borne encephalitis, is predicted to become 5–7% more prevalent on livestock farms in Great Britain, depending on the extent of future climate change.

Even after conception, a pregnancy is less likely to be carried to term due to reduced endometrial function and uterine blood flow, leading to increased embryonic mortality and early fetal loss.

Cattle eat less when they experience acute heat stress during hottest parts of the day, only to compensate when it is cooler, and this disbalance soon causes acidosis, which can lead to laminitis.

Additionally, one of the ways cattle can attempt to deal with higher temperatures is by panting more often, which rapidly decreases carbon dioxide concentrations and increases pH.

"[2] Bovine neutrophil function is impaired at higher temperatures, leaving mammary glands more vulnerable to infection,[60] and mastitis is already known to be more prevalent during the summer months, so there is an expectation this would worsen with continued climate change.

[2] One of the vectors of bacteria which cause mastitis are Calliphora blowflies, whose numbers are predicted to increase with continued warming, especially in the temperate countries like the United Kingdom.

[64] Since more variable and therefore less predictable precipitation is one of the well-established effects of climate change on the water cycle,[65]: 85 similar patterns were later established across the rest of the United States,[66] and then globally.

Yet, prolonged exposure to very hot and/or humid conditions will lead to consequences such as anhidrosis, heat stroke, or brain damage, potentially culminating in death if not addressed with measures like cold water applications.

[78] Parasitic worms Haemonchus contortus and Teladorsagia circumcincta are predicted to spread more easily amongst small ruminants as the winters become milder due to future warming, although in some places this is counteracted by summers getting hotter than their preferred temperature.

[63] Earlier, similar effects have been observed with two other parasitic worms, Parelaphostrongylus odocoilei and Protostrongylus stilesi, which have already been able to reproduce for a longer period inside sheep due to milder temperatures in the sub-Arctic.

[8] One paper estimated that in Austria, at an intensive farming facility used to fatten up about 1800 growing pigs at a time, the already observed warming between 1981 and 2017 would have increased relative annual heat stress by between 0.9 and 6.4% per year.

[80] Average daily temperatures of around 33 °C (91 °F) are known to interfere with feeding in both broilers and egg hens, as well as lower their immune response, with outcomes such as reduced weight gain/egg production or greater incidence of salmonella infections, footpad dermatitis or meningitis.

Multiple studies show that dietary supplementation with chromium can help to relieve these issues due to its antioxidative properties, particularly in combination with zinc or herbs like wood sorrel.

[92] By mid-2010s, indigenous people of the Arctic have already observed reindeer breeding less and surviving winters less often, as warmer temperatures benefit biting insects and result in more intense and persistent swarm attacks.