Einstein's thought experiments

A hallmark of Albert Einstein's career was his use of visualized thought experiments (German: Gedankenexperiment[1]) as a fundamental tool for understanding physical issues and for elucidating his concepts to others.

In his debates with Niels Bohr on the nature of reality, he proposed imaginary devices that attempted to show, at least in concept, how the Heisenberg uncertainty principle might be evaded.

As he grew older, his early thought experiment acquired deeper levels of significance: Einstein felt that Maxwell's equations should be the same for all observers in inertial motion.

[6]: 114–115 Regardless of the historical and scientific issues described above, Einstein's early thought experiment was part of the repertoire of test cases that he used to check on the viability of physical theories.

Norton suggests that the real importance of the thought experiment was that it provided a powerful objection to emission theories of light, which Einstein had worked on for several years prior to 1905.

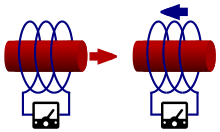

In the very first paragraph of Einstein's seminal 1905 work introducing special relativity, he writes: It is well known that Maxwell's electrodynamics—as usually understood at present—when applied to moving bodies, leads to asymmetries that do not seem to attach to the phenomena.

Maxwell, for instance, had repeatedly discussed Faraday's laws of induction, stressing that the magnitude and direction of the induced current was a function only of the relative motion of the magnet and the conductor, without being bothered by the clear distinction between conductor-in-motion and magnet-in-motion in the underlying theoretical treatment.

Documentary evidence concerning the development of the ideas that went into it consist of, quite literally, only two sentences in a handful of preserved early letters, and various later historical remarks by Einstein himself, some of them known only second-hand and at times contradictory.

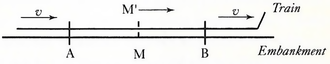

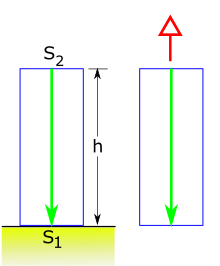

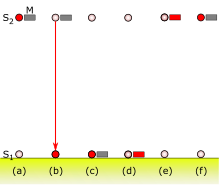

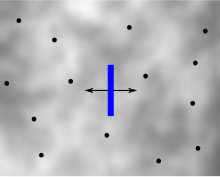

[8] In regards to the relativity of simultaneity, Einstein's 1905 paper develops the concept vividly by carefully considering the basics of how time may be disseminated through the exchange of signals between clocks.

[16] In his popular work, Relativity: The Special and General Theory, Einstein translates the formal presentation of his paper into a thought experiment using a train, a railway embankment, and lightning flashes.

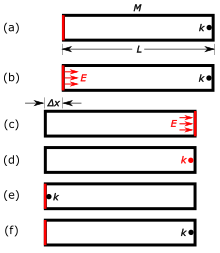

The reactionless drive described here violates the laws of mechanics, according to which the center of mass of a body at rest cannot be displaced in the absence of external forces.

The simple answer is that this question presupposes an absolute nature of time, when in fact there is nothing that compels us to assume that clocks situated at different gravitational potentials must be conceived of as going at the same rate.

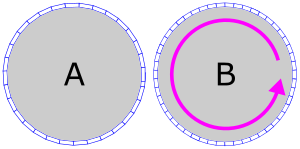

[29] In later years, Einstein repeatedly stated that consideration of the rapidly rotating disk was of "decisive importance" to him because it showed that a gravitational field causes non-Euclidean arrangements of measuring rods.

[30] Einstein realized that he did not have the mathematical skills to describe the non-Euclidean view of space and time that he envisioned, so he turned to his mathematician friend, Marcel Grossmann, for help.

The best-known factoids about Einstein's relationship with quantum mechanics are his statement, "God does not play dice with the universe" and the indisputable fact that he just did not like the theory in its final form.

Of this paper, Pais was to write: The only part of this article that will ultimately survive, I believe, is this last phrase [i.e. "No reasonable definition of reality could be expect to permit this" where "this" refers to the instantaneous transmission of information over a distance], which so poignantly summarizes Einstein's views on quantum mechanics in his later years....This conclusion has not affected subsequent developments in physics, and it is doubtful that it ever will.

Einstein imagined a mirror in a cavity containing particles of an ideal gas and filled with black-body radiation, with the entire system in thermal equilibrium.

Throughout most of this period, the physics community treated the light-quanta hypothesis with "skepticism bordering on derision"[12]: 357 and maintained this attitude even after Einstein's photoelectric law was validated.

The citation for Einstein's 1922 Nobel Prize very deliberately avoided all mention of light-quanta, instead stating that it was being awarded for "his services to theoretical physics and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect".

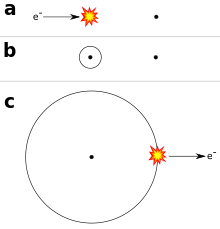

All the energy spread around the circumference of the radiating electromagnetic wave would appear to be instantaneously focused on the target atom, an action that Einstein considered implausible.

[6]: 325–326 [12]: 443–446 Over dinner, during after-dinner discussions, and at breakfast, Einstein debated with Bohr and his followers on the question whether quantum mechanics in its present form could be called complete.

Einstein illustrated his points with increasingly clever thought experiments intended to prove that position and momentum could in principle be simultaneously known to arbitrary precision.

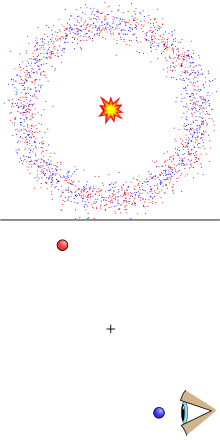

Quantum mechanics, at least in the Copenhagen interpretation, appeared to allow action at a distance, the ability for two separated objects to communicate at speeds greater than light.

By 1928, the consensus was that Einstein had lost the debate, and even his closest allies during the Fifth Solvay Conference, for example Louis de Broglie, conceded that quantum mechanics appeared to be complete.

With this gadget, Einstein believed that he had demonstrated a means to obtain, simultaneously, a precise determination of the energy of the photon as well as its exact time of departure from the system.

The following September, Einstein nominated Heisenberg and Schroedinger for the Nobel Prize, stating, "I am convinced that this theory undoubtedly contains a part of the ultimate truth.

[6]: 460–461 Einstein's beliefs had evolved over the years from those that he had held when he was young, when, as a logical positivist heavily influenced by his reading of David Hume and Ernst Mach, he had rejected such unobservable concepts as absolute time and space.

After leaving Nazi Germany and settling in Princeton at the Institute for Advanced Study, Einstein began writing up a thought experiment that he had been mulling over since attending a lecture by Léon Rosenfeld in 1933.

[note 16] The result of their collaboration was the four page EPR paper, which in its title asked the question Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality be Considered Complete?

Bell's theorem showed that, for any local realist formalism, there exist limits on the predicted correlations between pairs of particles in an experimental realization of the EPR thought experiment.