Eleanor of Castile

After diplomatic efforts to secure her marriage and affirm English sovereignty over Gascony, 13-year-old Eleanor was married to Edward at the monastery of Las Huelgas, Burgos, on 1 November 1254.

Fuller records of Eleanor's life with Edward start from the time of the Second Barons' War onwards, when Simon de Montfort's government imprisoned her in Westminster Palace.

This series of monuments may have included the renovated tomb of Little St Hugh – who was falsely believed to have been ritually murdered by Jews – to bolster her reputation as an opponent of supposed Jewish criminality.

After her death, Eleanor's reputation was shaped by conflicting fictitious accounts – both positive and negative – portraying her as either the dedicated companion of Edward I or as a scheming Spaniard.

[4][b] Because her parents were separated for 13 months while King Ferdinand was on a military campaign in Andalusia – from which he returned to the north of Spain in February 1241 – Eleanor was probably born towards the end of that year.

In 1253, Ferdinand III's heir Alfonso X of Castile – Eleanor's half-brother – appears to have stalled negotiations with England in the hope she would marry Theobald II of Navarre.

Rumours Eleanor was seeking fresh troops from Castile led the baronial leader Simon de Montfort to order her removal from Windsor Castle in June 1264 after the defeat of the royalist army at the Battle of Lewes.

Bonds for lands could be sold to recoup against a defaulted debt but these could only be traded by royal permission, meaning Eleanor and a select group of very wealthy courtiers were the exclusive beneficiaries of these sales.

Popular poem, quoted by Walter of Guisborough: The king would like to get our gold, the queen, our manors fair, to hold ...[38] By the 1270s, this situation had led the Jewish community into a desperate position while Edward, Eleanor and a few others gained vast new estates.

[39] John Peckham, Archbishop of Canterbury, warned Eleanor's servants about her activities in the land market and her association with the highly unpopular moneylenders: A rumour is waxing strong throughout the kingdom and has generated much scandal.

[50] Notwithstanding the manner by which she acquired her estates and income, Eleanor of Castile's queenship is significant in English history for the evolution of a stable financial system for the king's wife and for the honing this process gave the queen-consort's prerogatives.

Although the evidence was largely fictional, around ten percent of the Jewish population – over 300 individuals – was sentenced to death; their assets were seized and forfeit to the Crown, together with fines for those who escaped hanging.

[58] Eleanor played a role in Edward's counsels but she did not overtly exercise power except on occasions when she was appointed to mediate disputes between nobles in England and Gascony.

[62] As queen, Eleanor's major opportunity for power and influence would have come later in her life, when her sons grew older, by promoting their political and military careers.

[64] In a few cases, Eleanor's marriage projects for her female cousins provided Edward, as well as her father-in-law Henry III, with opportunities to sustain healthy relations with other realms.

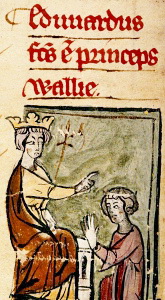

She was an active patron of literature, maintaining the only royal scriptorium known to have existed at the time in Northern Europe, with scribes and at least one illuminator to copy books for her.

[72] Eleanor popularised the use of tapestries and carpets;[72] the use of hangings and especially floor coverings was noted as a Spanish extravagance on her arrival in London but by the time of her death, it was much in vogue among rich magnates.

[76] Her household food supplies appear to have reflected her Spanish upbringing; they include olive oil, French cheese and fresh fruit.

The lack of material may be due to Eleanor's distance from the English Bishops, who represented traditional hierarchy, and her preference for the Dominican Order of Friars, to whom she was a patron, founding several priories in England and supporting their work at Oxford and Cambridge Universities.

[91] Two letters from Peckham show some people thought Eleanor urged Edward to rule harshly, and that she could be a severe woman who did not take it lightly if anyone crossed her, contravening contemporaneous expectations that queens should intercede with their husbands on behalf of the needy, the oppressed and the condemned.

[100] In mid 1290, a tour north through Eleanor's properties began, but proceeded much more slowly than usual, and the autumn Parliament was convened in Clipstone rather than in London.

[104] Edward was greatly affected by Eleanor's death, shown for instance in his January 1291 letter to the abbot of Cluny in France, in which he sought prayers for the soul of the wife "whom living we dearly cherished, and whom dead we cannot cease to love".

[108] These artistically significant monuments, which were based on crosses in France marking Louis IX's funeral procession, enhanced the image of Edward's kingship and bear witness to his grief.

[109] Eleanor crosses stood at Lincoln, Grantham, Stamford, Geddington, Hardingstone near Northampton, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St Albans, Waltham, Westcheap and Charing.

[116] According to historians Caroline and Joe Hillaby, the crosses and tomb amounted to a "propaganda coup", rehabilitating Eleanor's image and portraying her as the protector of Christians against the supposed criminality of Jews following the expulsion of the Jewry.

The accounts of her executors show the monument constructed at the priory to commemorate her heart burial was richly elaborate, and included wall paintings and a metallic angelic statue that stood under a carved stone canopy.

Eleanor's tomb, which she had probably ordered before her death, consists of a marble chest with carved mouldings and shields – originally painted – of the arms of England, Castile and Ponthieu.

[d] In 1587, Raphael Holinshed's Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland described Eleanor as "the jewel [Edward I] most esteemed ... a godly and modest princess, full of pity, and one that showed much favour to the English nation, ready to relieve every man's grief that sustained wrong and to make them friends that were at discord, so far as in her lay.

The surviving revised version, which was printed in 1593, depicts Eleanor as a haughty "villainess capable of unspeakable treachery, cruelty, and depravity"; she is also depicted as intransigent and hubristic, "concerned primarily with enhancing the reputation of her native nation, and evidently accustomed to a tyrannous and quite un-English exercise of royal prerogative"; delaying her coronation for twenty weeks so she can have Spanish dresses made, and proclaiming she shall keep the English under a "Spanish yoke".

This portrait of Eleanor owes little to historicity, and much to the then-current war with Spain and English fears of another attempt at invasion, and is one of a number of anti-Spanish polemics of the period.