Electrodynamic tether

A number of missions have demonstrated electrodynamic tethers in space, most notably the TSS-1, TSS-1R, and Plasma Motor Generator (PMG) experiments.

In 2012 Star Technology and Research was awarded a $1.9 million contract to qualify a tether propulsion system for orbital debris removal.

Potential tether applications can be seen below: EDT has been proposed to maintain the ISS orbit and save the expense of chemical propellant reboosts.

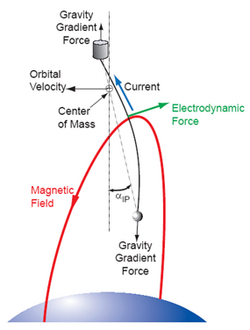

[4][5][6][7][8] At 300 km altitude, the Earth's magnetic field, in the north-south direction, is approximately 0.18–0.32 gauss up to ~40° inclination, and the orbital velocity with respect to the local plasma is about 7500 m/s.

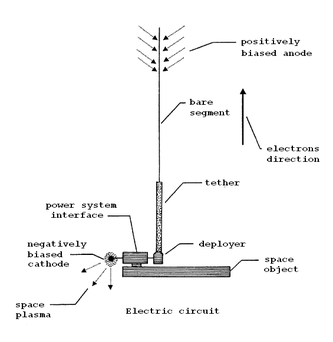

This flow of electrons through the length of the tether in the presence of the Earth's magnetic field creates a force that produces a drag thrust that helps de-orbit the system, as given by the above equation.

Since the current is continuously changing along the bare length of the tether, the potential loss due to the resistive nature of the wire is represented as

In a loose sense, the process can be likened to a conventional windmill- the drag force of a resistive medium (air or, in this case, the magnetosphere) is used to convert the kinetic energy of relative motion (wind, or the satellite's momentum) into electricity.

In principle, compact high-current tether power generators are possible and, with basic hardware, tens, hundreds, and thousands of kilowatts appears to be attainable.

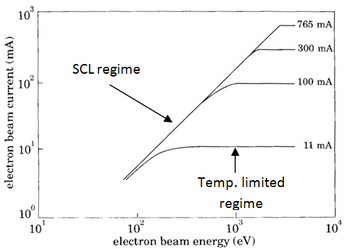

The electron and ion density varies according to various factors, such as the location, altitude, season, sunspot cycle, and contamination levels.

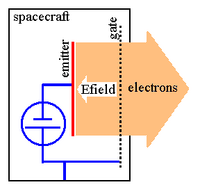

The batteries in return will be used to control power and communication circuits, as well as drive the electron emitting devices at the negative end of the tether.

Any exposed conducting section of the EDT system can passively ('passive' and 'active' emission refers to the use of pre-stored energy in order to achieve the desired effect) collect electron or ion current, depending on the electric potential of the spacecraft body with respect to the ambient plasma.

In addition, the collection along a thin bare tether is described using orbital motion limited (OML) theory as well as theoretical derivations from this model depending on the physical size with respect to the plasma Debye length.

As the effective radius of the bare conductive tether increases past this point then there are predictable reductions in collection efficiency compared to OML theory.

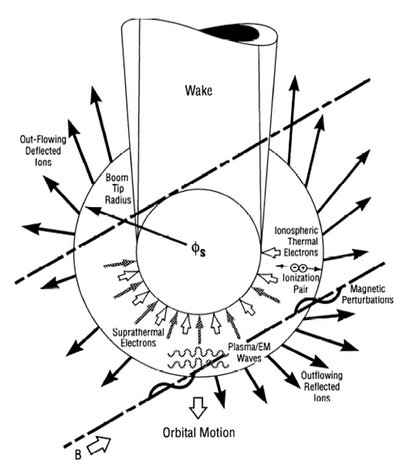

OML theory[14] is defined with the assumption that the electron Debye length is equal to or larger than the size of the object and the plasma is not flowing.

This accelerating (or decelerating) voltage combined with the energy and momentum of the incoming particles determines the amount of current collected across the plasma sheath.

This section discusses the plasma physics theory that explains passive current collection to a large conductive body which will be applied at the end of an ED tether.

In a non-flowing quasi-neutral plasma with no magnetic field, it can be assumed that a spherical conducting object will collect equally in all directions.

When the conducting body is negatively biased with respect to the plasma and traveling above the ion thermal velocity, there are additional collection mechanisms at work.

The thermionic emission current density, J, rises rapidly with increasing temperature, releasing a significant number of electrons into the vacuum near the surface.

[39] Once the electrons are thermionically emitted from the TC surface they require an acceleration potential to cross a gap, or in this case, the plasma sheath.

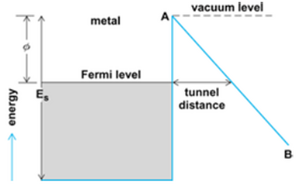

In the presence of a strong electric field, the potential outside the metal will be deformed along the line AB, so that a triangular barrier is formed, through which electrons can tunnel.

Electrons are extracted from the conduction band with a current density given by the Fowler−Nordheim equation AFN and BFN are the constants determined by measurements of the FEA with units of A/V2 and V/m, respectively.

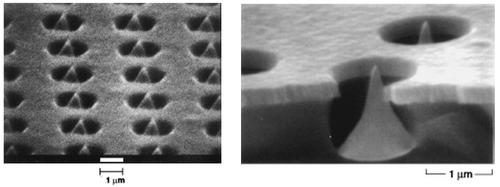

[44] Close (micrometer scale) proximity between the emitter and gate, combined with natural or artificial focusing structures, efficiently provide the high field strengths required for emission with relatively low applied voltage and power.

A carbon nanotube field-emission cathode was successfully tested on the KITE Electrodynamic tether experiment on the Japanese H-II Transfer Vehicle.

In order to achieve electron emission at low voltages, field emitter array tips are built on a micrometer-level scale sizes.

[44] Techniques for avoiding, eliminating, or operating in the presence of contaminations in ground testing and ionospheric (e.g. spacecraft outgassing) environments are critical.

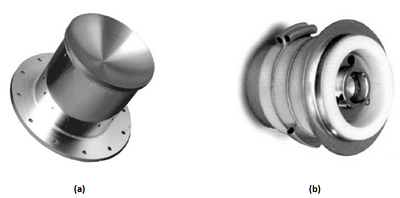

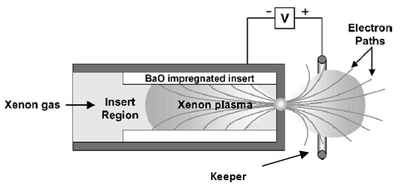

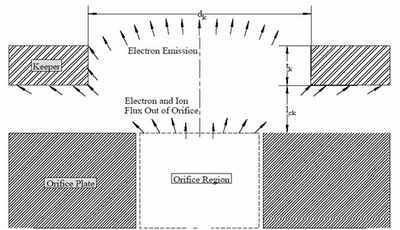

[50][51][52][53] One type of hollow cathode consists of a metal tube lined with a sintered barium oxide impregnated tungsten insert, capped at one end by a plate with a small orifice, as shown in the below figure.

Given a certain keeper geometry (the ring in the figure above that the electrons exit through), ion flow rate, and Vp, the I-V profile can be determined.

[61][62][63][64] In order to integrate all the most recent electron emitters, collectors, and theory into a single model, the EDT system must first be defined and derived.

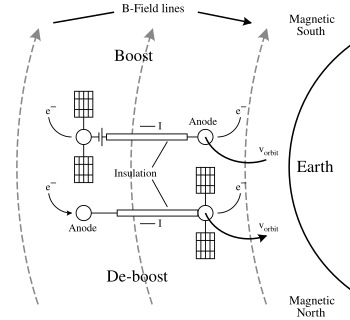

In the below figure, the magnetic field vector is solely in the north (or y-axis) direction, and the resulting forces on an orbit, with some inclination, can be seen.