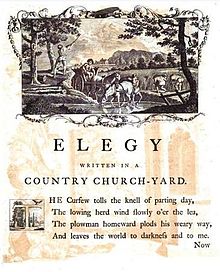

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard

But while many have continued to commend its language and universal aspects, some have felt that the ending is unconvincing – failing to resolve the questions raised by the poem in a way helpful to the obscure rustic poor who form its central image.

[24] In evoking the English countryside, the poem belongs to the picturesque tradition found in John Dyer's Grongar Hill (1726), and the long line of topographical imitations it inspired.

The speaker emphasises both aural and visual sensations as he examines the area in relation to himself:[32] The curfew tolls the knell of parting day, The lowing herd wind slowly o'er the lea, The ploughman homeward plods his weary way, And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

Now fades the glimmering landscape on the sight, And all the air a solemn stillness holds, Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight, And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds:

Th' applause of list'ning senates to command, The threats of pain and ruin to despise, To scatter plenty o'er a smiling land, And read their history in a nation's eyes,

The struggling pangs of conscious truth to hide, To quench the blushes of ingenuous shame, Or heap the shrine of luxury and pride With incense kindled at the Muse's flame.

Hard by yon wood, now smiling as in scorn, Mutt'ring his wayward fancies he would rove; Now drooping, woeful-wan, like one forlorn, Or craz'd with care, or cross'd in hopeless love.

Circumstance kept the poet from becoming something greater, and he was separated from others because he was unable to join in the common affairs of their life:[40] Here rests his head upon the lap of earth A youth, to fortune and to fame unknown: Fair science frown'd not on his humble birth, And melancholy mark'd him for her own.

how the sacred calm, that breathes around, Bids every fierce tumultuous passion cease; In still small accents whisp'ring from the ground, A grateful earnest of eternal peace.

No more, with reason and thyself at strife, Give anxious cares and endless wishes room; But through the cool sequester'd vale of life Pursue the silent tenour of thy doom.

[52] Many scholars, including Lonsdale, believe that the poem's message is too universal to require a specific event or place for inspiration, but Gray's letters suggest that there were historical influences in its composition.

[31] Once Gray had set the example, any occasion would do to give a sense of the effects of time in a landscape, as for instance in the passage of the seasons as described in John Scott's Four Elegies, descriptive and moral (1757).

[62] A kinship between Gray's Elegy and Oliver Goldsmith's The Deserted Village has been recognised, although the latter was more openly political in its treatment of the rural poor and used heroic couplets, where the elegist poets kept to cross-rhymed quatrains.

[86] Ambrose Bierce used parody of the poem for the same critical purpose in his definition of Elegy in The Devil's Dictionary, ending with the dismissive lines The wise man homeward plods; I only stay To fiddle-faddle in a minor key.

[91] These include ambiguities of word order and the fact that certain languages do not allow the understated way in which Gray indicates that the poem is a personalised statement in the final line of the first stanza, "And leaves the world to darkness and to me".

There are certain images, which, though drawn from common nature, and everywhere obvious, yet strike us as foreign to the turn and genius of Latin verse; the beetle that flies in the evening, to a Roman, I guess, would have appeared too mean an object for poetry.

In fact, all that Anstey had dropped was reproducing an example of zeugma with a respectable Classical history, but only in favour of replicating the same understated introduction of the narrator into the scene: et solus sub nocte relinqor (and I alone am left under the night).

Both were subsequently included in Irish collections of Gray's poems, accompanied not only by John Duncombe's "Evening Contemplation", as noted earlier, but in the 1775 Dublin edition by translations from Italian sources as well.

[97] A French publication ingeniously followed suit by including the Elegy in an 1816 guide to the Père Lachaise Cemetery, accompanied by Torelli's Italian translation and Pierre-Joseph Charrin's free Le Cimetière de village.

[99] This included four translations into Latin, of which one was Christopher Anstey's and another was Costa's; eight into Italian, where versions in prose and terza rima accompanied those already mentioned by Torelli and Cesarotti; two in French, two in German and one each in Greek and Hebrew.

[122] The 18th-century writer James Beattie was said by Sir William Forbes, 6th Baronet to have written a letter to him claiming, "Of all the English poets of this age, Mr. Gray is most admired, and I think with justice; yet there are comparatively speaking but a few who know of anything of his, but his 'Church-yard Elegy,' which is by no means the best of his works.

"[129] He continued by stressing the poem's wide acceptance: "The fame of the Elegy has spread to all countries and has exercised an influence on all the poetry of Europe, from Denmark to Italy, from France to Russia.

With the exception of certain works of Byron and Shakespeare, no English poem has been so widely admired and imitated abroad and after more than a century of existence we find it as fresh as ever, when its copies, even the most popular of all those of Lamartine, are faded and tarnished.

The triumph of this sensibility allied to so much art is to be seen in the famous Elegy, which from a somewhat reasoning and moralizing emotion has educed a grave, full, melodiously monotonous song, in which a century weaned from the music of the soul tasted all the sadness of eventide, of death, and of the tender musing upon self.

A. Richards, following in 1929, declared that the merits of the poem come from its tone: "poetry, which has no other very remarkable qualities, may sometimes take very high rank simply because the poet's attitude to his listeners – in view of what he has to say – is so perfect.

"[135] T. S. Eliot's 1932 collection of essays contained a comparison of the elegy to the sentiment found in metaphysical poetry: "The feeling, the sensibility, expressed in the Country Churchyard (to say nothing of Tennyson and Browning) is cruder than that in the Coy Mistress.

In 1955, R. W. Ketton-Cremer argued, "At the close of his greatest poem Gray was led to describe, simply and movingly, what sort of man he believed himself to be, how he had fared in his passage through the world, and what he hoped for from eternity.

"[145] In 1971, Charles Cudworth declared that the elegy was "a work which probably contains more famous quotations per linear inch of text than any other in the English language, not even excepting Hamlet.

"[148] In 1978, Howard Weinbrot noted, "With all its long tradition of professional examination the poem remains distant for many readers, as if the criticism could not explain why Johnson thought that "The Church-yard abounds with images that find a mirrour in every mind".

In 1995, Lorna Clymer argued, "The dizzying series of displacements and substitutions of subjects, always considered a crux in Thomas Gray's "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard" (1751), results from a complex manipulation of epitaphic rhetoric.