Elizabeth Catlett

Her parents worked in education; her mother was an attendance officer; her father taught math at Tuskegee University, then the D.C. public school system.

[1][6] However, in 2007, as Tyra Butler, board member of the August Wilson Center for African American Culture in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was giving a talk to a youth group at an exhibition of prominent African-American artists in partnership with the August Wilson Center, she recounted Catlett's tie to Pittsburgh because of this injustice.

A Carnegie Mellon University administrator, Robbie Baker Kosak, attended as a guest of Tyra Butler and heard the story for the first time.

The Dean of the College of Fine Arts, Hilary Robinson, also saw an account of the refusal in an exhibition of Black artists in downtown Pittsburgh.

Tyra Butler, Stephanie and Michael Jasper, Claudette Lewis, and Yvonne Cook published and produced a catalog of Catlett's work, introduced by Dean Robinson, in conjunction with the exhibition.

[2][1][3][6] At the time, the idea of a career as an artist was far-fetched for a black woman, so she completed her undergraduate studies intending to be a teacher.

[1][7] Catlett became interested in the work of American painter Grant Wood, so she entered the graduate program where he taught at the University of Iowa.

[3][7][18] In 1942, the couple moved to New York, where Catlett taught adult education classes at the George Washington Carver School in Harlem.

She also studied lithography at the Art Students League of New York; she received private instruction from Russian sculptor Ossip Zadkine,[3][14] who urged her to add abstract elements to her figurative work.

[1] During her time in New York, she met intellectuals and artists such as Gwendolyn Bennett, W. E. B. Dubois, Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, Jacob Lawrence, Aaron Douglas, and Paul Robeson.

[18] In 1947, Catlett entered the Taller de Gráfica Popular, a workshop dedicated to prints promoting leftist social causes and education.

[1][3][14] In 1971, after a letter-writing campaign to the U.S. State Department by colleagues and friends, she was issued a special permit to attend an exhibition of her work at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

[1][7] After retiring from her teaching position at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas, Catlett moved to the city of Cuernavaca, Morelos, in 1975.

[1] Very early in her career, Catlett accepted a Public Works of Art Project assignment with the federal government for unemployed artists during the 1930s.

At the TGP, she and other artists created a series of linoleum cuts featuring prominent black figures, as well as posters, leaflets, illustrations for textbooks, and materials to promote literacy in Mexico.

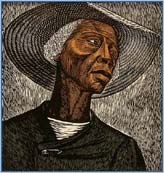

[26] Sharecropper, one of the linoleum cuts made at the TGP, is possibly her most famous work and is an excellent example of Catlett's bold visual style due to both the crisp black lines and rich brown and green inks of the drawing, and the halo of the hat brim and the upward looking angle of the composition making the figure monumental, or someone to be venerated, despite the poverty evidenced by the safety pin holding together the cloak.

[23][24][27] Catlett's immersion into the TGP was crucial for her appreciation and comprehension of the signification of "mestizaje", a blending of Indigenous, Spanish and African antecedents in Mexico, which was a parallel reality to African-American experiences.

[30] The Legacy Museum, which opened on April 26, 2018,[31] displays and dramatizes the history of slavery and racism in America and features artwork by Catlett and others.

[14] These include First Prize at the 1940 American Negro Exposition in Chicago,[34] induction into the Salón de la Plástica Mexicana in 1956,[3] the Distinguished Alumni Award from the University of Iowa in 1996,[16] a 1998 50-year traveling retrospective of her work sponsored by the Newberger Museum of Art at Purchase College,[2][3] an NAACP Image Award in 2009,[22] and a joint tribute after her death held by the Salón de la Plástica Mexicana and the Instituto Politécnico Nacional in 2013.

[7] She was the subject of an episode of the BBC Radio 4 series An Alternative History of Art, presented by Naomi Beckwith and broadcast on March 6, 2018.

Carnegie Mellon University, the school that denied her entrance in 1931 based on her race,[37] went on to bestow her with an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts degree in 2008.

[18] Her print work consisted mainly of woodcuts and linocuts, while her sculptures were composed of a variety of materials, such as clay, cedar, mahogany, eucalyptus, marble, limestone, onyx, bronze, and Mexican stone (cantera).

[19] Sculptures ranged in size and scope from small wood figures inches high to others several feet tall to monumental works for public squares and gardens.

[7] Much of her work is realistic and highly stylized two- or three-dimensional figures,[6] applying the Modernist principles (such as organic abstraction to create a simplified iconography to display human emotions) of Henry Moore, Constantin Brâncuși and Ossip Zadkine to popular and easily recognized imagery.

[18] Her imagery arises from a scrupulously honest dialogue with herself on her life and perceptions, and between herself and "the other", that is, contemporary society's beliefs and practices of racism, classism and sexism.

[17] Her subjects range from sensitive maternal images to confrontational symbols of Black Power, and portraits of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks, and writer Phillis Wheatley,[6][19] as she believed that art could play a role in the construction of transnational and ethnic identity.

[1][22] The women are voluptuous, with broad hips and shoulders, in positions of power and confidence, often with torsos thrust forward to show attitude.

[34] The Taller de Gráfica Popular pushed her to adapt her work to reach the broadest possible audience, which generally meant balancing abstraction with figurative images.

"[1] Critic Michasel Brenson noted the "fluid, sensual surfaces" of her sculptures, which he said "seem to welcome not just the embrace of light but also the caress of the viewer's hand".

"[7] Catlett's The Negro Woman, dated 1946–1947, is a series of 15 linoleum cuts highlighting the experience of discrimination and racism that African-American women were facing at the time.