Elizabeth Dilling

[6] Dilling was the best-known leader of the World War II women's isolationist movement, a grass-roots campaign that pressured Congress to refrain from helping the Allies.

[12][13] The family traveled abroad at least ten times between 1923 and 1939, experiences that focused Dilling's political outlook and served to convince her of American superiority.

Dilling wrote of her praise of Nazi Germany in 1936:"Nazism has directed its attacks more against conspiring, revolutionary Communist Jews, than against nationalist German Jews who aided Germany during the war; if it has discriminated against the innocent also, it has been with no such ferocity and loss of life as the planned and imminent Communist revolution would have wreaked upon the German population, had it been successful as in Russia.

We were appalled, not only at the forced labor, the squalid crowded living quarters, the breadline ration card workers’ stores, the mothers pushing wheelbarrows and begging children of the State nurseries besieging us.

Atheist cartoons representing Christ as a villain, a drunk, and the object of a cannibalistic orgy (Holy Communion): as an oppressor of labor; again as trash being dumped from a wheelbarrow by the Soviet Five-Year-Plan – these lurid cartoons filled the big bulletin boards in the churches our Soviet guides took us to visit.Dilling's political activism was spurred by the "bitter opposition" she encountered upon her return to Illinois in 1931, "against my telling the truth about Russia ... from suburbanite 'intellectual' friends and from my own Episcopal minister.

Iris McCord, a Chicago radio broadcaster who taught at the Moody Bible Institute, arranged for her to address local church groups.

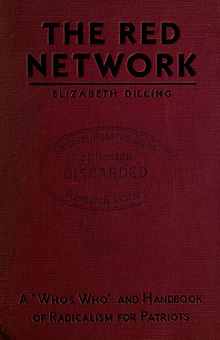

The second half contained descriptions of more than 1,300 "Reds" (including international figures such as Albert Einstein and Chiang Kai-shek), and more than 460 organizations described as "Communist, Radical Pacifist, Anarchist, Socialist, [or] I.W.W.

[26][29] In 1935, Dilling returned to her alma mater to accuse such people as university president Robert Maynard Hutchins, educational reformer John Dewey, activist Jane Addams, and Republican Senator William Borah of being communist sympathizers.

[30] Retail tycoon Charles R. Walgreen asked for her help to obtain a public hearing after his niece complained that professors at the university were communists.

[iii][34][35][36] In 1938, Dilling founded the Patriotic Research Bureau, a vast archive in Chicago with a staff of "Christian women and girls" from the Moody Bible Institute.

She began regular publication of the Patriotic Research Bulletin, a newsletter outlining her political and personal views, which she mailed free of charge to her supporters.

She stated: "It airs their dirty lying attempts to shut every Christian mouth and prevent anyone from getting a fair trial in this country" (for which she was cited for contempt).

One telling example was when a federal subpoena in 1941, issued by the Justice Department, ordered her to Washington DC to explain her alleged affiliations with Nazi sympathizers.

A sincere act of humility this was not, but it did reveal Dilling's inclination for martyrdom and self-importance, as well as a talent for propaganda.Dilling was a central figure in a mass movement of isolationist women's groups, which opposed US involvement in World War II from a "maternalist" perspective.

[45][46][47] According to historian Kari Frederickson: "They argued that war was the antithesis of nurturant motherhood, and that as women they had a particular stake in preventing American involvement in the European conflict.

"[10] The movement was strongest in the Midwest, a conservative stronghold with a culture of antisemitism, which had long resented the political dominance of the East Coast.

Chicago was the base of far-right activists Charles E. Coughlin, Gerald L. K. Smith and Lyrl Clark Van Hyning, as well as the America First Committee, which had 850,000 members by 1941.

[v][36][49][50] In early 1941, when the movement was at its height, Dilling spoke at rallies in Chicago and other cities in the Midwest, and recruited a group to coordinate her efforts to oppose Lend-Lease, the "Mothers' Crusade to Defeat H. R. 1776".

Isolationist leader Cathrine Curtis believed that the image of the Mothers' movement had been wrecked, and privately criticised Dilling's "hoodlum" tactics as "communistic" and "un-womanly".

[55] Her political activity decreased as a result of her highly publicized divorce trial, beginning in February 1942, during which dozens of fist fights broke out, involving both men and women, and Dilling received three citations for contempt.

[vi][57][58] A grand jury, convened in 1941 to investigate fascist propaganda, called several women's leaders to testify, including Dilling, Curtis and Van Hyning.

Roosevelt prevailed upon Attorney General Francis Biddle to launch a prosecution, and on July 21, 1942, Dilling and 27 other anti-war activists were indicted on two counts of conspiracy to cause insubordination of the military in peacetime and wartime.

The case was the main part of a government campaign against domestic subversion, which historian Leo P. Ribuffo labelled "The Brown Scare".

The charges were dismissed by federal judge Bolitha Laws on November 22, 1946, after the government had failed to present any compelling new evidence of a German conspiracy.

[62] The book purports to "reveal the satanic hatred of Christ and Christians responsible for their mass murder, torture and slave labour in all Iron Curtain countries – all of which are ruled by Talmudists".

[63]The UN Charter and treaties are constructed to make way for the "man of sin," the Anti-Christ who will hold supreme power over life or death as he briefly heads this last Red satanic world empire.Dilling died on April 30, 1966, in Lincoln, Nebraska.

[64] According to the Library of Congress records, Dilling self-published the original printings of her books in Kenilworth, Illinois, then some 20 miles north of downtown Chicago.