Elizabeth Singer Rowe

[4] Despite a posthumous reputation as a pious, bereaved recluse, Rowe corresponded widely and was involved in local concerns at Frome in her native Somerset.

She was of a moderate stature, her hair of a fine auburn colour, and her eyes of a darkish grey inclining to blue, and full of fire.

"[9] Rowe's mother died when she was about 18, and her father moved the family to Egford Farm, Frome, Somerset, where she was tutored in French and Italian by Henry Thynne, son of the first Viscount Weymouth of Longleat, Wiltshire.

[10] The connections Rowe made at Longleat benefited her literary career and initiated a lifelong friendship with Frances Thynne, the viscount's daughter.

[7] Although courted by John Dunton, Matthew Prior and Isaac Watts, she married the poet and biographer Thomas Rowe, 13 years her junior, in 1710.

"[7][14] Between 1693 and 1696 she was the principal contributor of poetry to Dunton's The Athenian Mercury, but later regretted her affiliation with him, as "a print-world impresario" whose adaptions of masculine gallantry to commercial print were "ridiculed" by the literati.

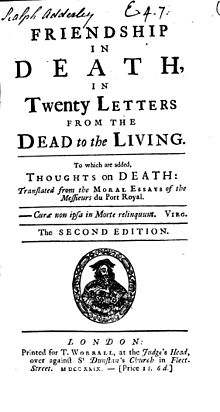

[21] In the preface, Rowe states her didactic intent, "The Drift of these Letters is, to impress the Notion of the Soul's Immortality; without which, all Virtue and Religion, with their Temporal and Eternal good Consequences, must fall to the Ground.

Perhaps best described as a didactic miscellany, this work also contained religious poetry, pastorals, translations of Tasso and actual letters from the correspondence between Rowe and Lady Hertford.

This, however, is not all their praise; they have laboured to add to her brightness of imagery, her purity of sentiment" and he gave her credit for a mastery of style which used the "ornaments of romance in the decoration of religion".

[30] Eighteenth-century English writer and bluestocking Elizabeth Carter lauded Rowe's "happy elegance of thought," describing her verse as "refin'd by virtue" with "powerful strains [that] wake the nobler passions of the soul.

"[32] George Ballard, 18th-century literary antiquarian and biographer, held up Rowe as the epitome of his domesticated model of the virtuous and modest, ideal woman writer in his highly influential Memoirs of Several Ladies of Great Britain: who have been celebrated for their writings or skill in the learned languages, arts and sciences (1752).

[34] As late as 1803 an anonymous writer suggested that Rowe represented “Virtue and all her genuine beauty [that should] recommend her to the choice and admiration of a rising generation.

[36] Her works were reprinted nearly annually until 1855, out of print by 1860, and in 1897 she was not even mentioned in A Dictionary of English Authors; her reputation had gone from "exemplar" and "muse" to "antiquarian curiosity.

"[37] Recent scholars have interpreted Rowe as a pivotal figure in the development of the English novel: Rowe borrowed stock characters and situations from the late 17th and early 18th-century French and Italian romances popular in England, transforming the outward struggles to save the body of the heroine from seducers, to saving the mind and soul of the heroine from the corrupt world through the virtuous self-control that results from contemplation, thus sealing the plot trajectory of subsequent fiction as evidenced in later novels such as Eliza Haywood's Betsy Thoughtless, Samuel Richardson's Clarissa and Frances Burney's Cecilia.