Elliptic geometry

However, unlike in spherical geometry, two lines are usually assumed to intersect at a single point (rather than two).

The elliptic lines correspond to great circles reduced by the identification of antipodal points.

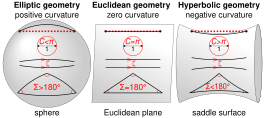

As any two great circles intersect, there are no parallel lines in elliptic geometry.

Any point on this polar line forms an absolute conjugate pair with the pole.

[1]: 89 The distance between a pair of points is proportional to the angle between their absolute polars.

Kepler and Desargues used the gnomonic projection to relate a plane σ to points on a hemisphere tangent to it.

Thus the axiom of projective geometry, requiring all pairs of lines in a plane to intersect, is confirmed.

[3] Given P and Q in σ, the elliptic distance between them is the measure of the angle POQ, usually taken in radians.

Arthur Cayley initiated the study of elliptic geometry when he wrote "On the definition of distance".

For example, the first and fourth of Euclid's postulates, that there is a unique line between any two points and that all right angles are equal, hold in elliptic geometry.

Therefore any result in Euclidean geometry that follows from these three postulates will hold in elliptic geometry, such as proposition 1 from book I of the Elements, which states that given any line segment, an equilateral triangle can be constructed with the segment as its base.

The ratio of a circle's circumference to its area is smaller than in Euclidean geometry.

In general, area and volume do not scale as the second and third powers of linear dimensions.

As directed line segments are equipollent when they are parallel, of the same length, and similarly oriented, so directed arcs found on great circles are equipollent when they are of the same length, orientation, and great circle.

Access to elliptic space structure is provided through the vector algebra of William Rowan Hamilton: he envisioned a sphere as a domain of square roots of minus one.

Hamilton called his algebra quaternions and it quickly became a useful and celebrated tool of mathematics.

When doing trigonometry on Earth or the celestial sphere, the sides of the triangles are great circle arcs.

[6] Hamilton called a quaternion of norm one a versor, and these are the points of elliptic space.

In the case u = 1 the elliptic motion is called a right Clifford translation, or a parataxy.

The points of n-dimensional elliptic space are the pairs of unit vectors (x, −x) in Rn+1, that is, pairs of antipodal points on the surface of the unit ball in (n + 1)-dimensional space (the n-dimensional hypersphere).

Lines in this model are great circles, i.e., intersections of the hypersphere with flat hypersurfaces of dimension n passing through the origin.

The points of n-dimensional projective space can be identified with lines through the origin in (n + 1)-dimensional space, and can be represented non-uniquely by nonzero vectors in Rn+1, with the understanding that u and λu, for any non-zero scalar λ, represent the same point.

Let En represent Rn ∪ {∞}, that is, n-dimensional real space extended by a single point at infinity.

We also define The result is a metric space on En, which represents the distance along a chord of the corresponding points on the hyperspherical model, to which it maps bijectively by stereographic projection.

We obtain a model of spherical geometry if we use the metric Elliptic geometry is obtained from this by identifying the antipodal points u and −u / ‖u‖2, and taking the distance from v to this pair to be the minimum of the distances from v to each of these two points.

Tarski proved that elementary Euclidean geometry is complete: there is an algorithm which, for every proposition, can show it to be either true or false.