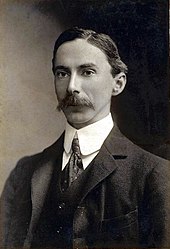

Alfred North Whitehead

He created the philosophical school known as process philosophy,[2] which has been applied in a wide variety of disciplines, including ecology, theology, education, physics, biology, economics, and psychology.

Griffin retells Russell's story of how, one evening in 1901, "they found Evelyn Whitehead in the middle of what appeared to be a dangerous and acutely painful angina attack.

[10] Intensity of emotion was encouraged by their avant-garde associates in the turbulent Bloomsbury Group which "discussed aesthetic and philosophical questions in a spirit of agnosticism and were strongly influenced by G.E.

[11] Alfred's brother Henry became Bishop of Madras and wrote the closely observed ethnographic account Village Gods of South-India (Calcutta: Association Press, 1921).

However, many details of Whitehead's life remain obscure because he left no Nachlass (personal archive); his family carried out his instructions that all of his papers be destroyed after his death.

[38] Whitehead credits William Rowan Hamilton and Augustus De Morgan as originators of the subject matter, and James Joseph Sylvester with coining the term itself.

Whitehead and Russell were working on such a foundational level of mathematics and logic that it took them until page 86 of Volume II to prove that 1+1=2, a proof humorously accompanied by the comment, "The above proposition is occasionally useful.

[46] When it came time for publication, the three-volume work was so long (more than 2,000 pages) and its audience so narrow (professional mathematicians) that it was initially published at a loss of 600 pounds, 300 of which was paid by Cambridge University Press, 200 by the Royal Society of London, and 50 apiece by Whitehead and Russell themselves.

In addition to his numerous individually written works on the subject, Whitehead was appointed by Britain's Prime Minister David Lloyd George as part of a 20-person committee to investigate the educational systems and practices of the UK in 1921 and recommend reform.

No headmaster has a free hand to develop his general education or his specialist studies in accordance with the opportunities of his school, which are created by its staff, its environment, its class of boys, and its endowments.

[58]Whitehead argued that curriculum should be developed specifically for its own students by its own staff, or else risk total stagnation, interrupted only by occasional movements from one group of inert ideas to another.

Though Process and Reality has been called "arguably the most impressive single metaphysical text of the twentieth century,"[74] it has been little-read and little-understood, partly because it demands – as Isabelle Stengers puts it – "that its readers accept the adventure of the questions that will separate them from every consensus.

"[75] Whitehead questioned Western philosophy's most dearly held assumptions about how the universe works – but in doing so, he managed to anticipate a number of 21st century scientific and philosophical problems and provide novel solutions.

In his 1925 book Science and the Modern World, he wrote that: There persists ... [a] fixed scientific cosmology which presupposes the ultimate fact of an irreducible brute matter, or material, spread through space in a flux of configurations.

In this way of thinking, things and people are seen as fundamentally the same through time, with any changes being qualitative and secondary to their core identity (e.g., "Mark's hair has turned grey as he has gotten older, but he is still the same person").

Whitehead pointed to the limitations of language as one of the main culprits in maintaining a materialistic way of thinking and acknowledged that it may be difficult to ever wholly move past such ideas in everyday speech.

Moreover, the inability to predict an electron's movement (for instance) is not due to faulty understanding or inadequate technology; rather, the fundamental creativity/freedom of all entities means that there will always remain phenomena that are unpredictable.

In keeping with his process metaphysics in which relations are primary, he wrote that religion necessitates the realization of "the value of the objective world which is a community derivative from the interrelations of its component individuals.

[120] Whitehead also described religion more technically as "an ultimate craving to infuse into the insistent particularity of emotion that non-temporal generality which primarily belongs to conceptual thought alone.

"[121] In other words, religion takes deeply felt emotions and contextualizes them within a system of general truths about the world, helping people to identify their wider meaning and significance.

Isabelle Stengers wrote that "Whiteheadians are recruited among both philosophers and theologians, and the palette has been enriched by practitioners from the most diverse horizons, from ecology to feminism, practices that unite political struggle and spirituality with the sciences of education.

"[75] In recent decades, attention to Whitehead's work has become more widespread, with interest extending to intellectuals in Europe and China, and coming from such diverse fields as ecology, physics, biology, education, economics, and psychology.

[123] However, it was not until the 1970s and 1980s that Whitehead's thought drew much attention outside of a small group of philosophers and theologians, primarily Americans, and even today he is not considered especially influential outside of relatively specialized circles.

[57] Cobb has attributed China's interest in process philosophy partly to Whitehead's stress on the mutual interdependence of humanity and nature, as well as his emphasis on an educational system that includes the teaching of values rather than simply bare facts.

[136] Other notable process theologians include John B. Cobb, David Ray Griffin, Marjorie Hewitt Suchocki, C. Robert Mesle, Roland Faber, and Catherine Keller.

In Syntheism – Creating God in The Internet Age, futurologists Alexander Bard and Jan Söderqvist repeatedly credit Whitehead for the process theology they see rising out of the participatory culture expected to dominate the digital era.

[141] Scientists of the early 20th century for whom Whitehead's work has been influential include physical chemist Ilya Prigogine, biologist Conrad Hal Waddington, and geneticists Charles Birch and Sewall Wright.

Brian G. Henning, Adam Scarfe, and Dorion Sagan's Beyond Mechanism (2013) and Rupert Sheldrake's Science Set Free (2012) are examples of Whiteheadian approaches to biology.

[154] Cobb also co-authored a book with leading ecological economist and steady-state theorist Herman Daly entitled For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy toward Community, the Environment, and a Sustainable Future (1989), which applied Whitehead's thought to economics, and received the Grawemeyer Award for Ideas Improving World Order.

Cobb followed this with a second book, Sustaining the Common Good: A Christian Perspective on the Global Economy (1994), which aimed to challenge "economists' zealous faith in the great god of growth.