Emancipation of the British West Indies

[1] The Haitian Revolution in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, the most successful slave uprising in the Americas, heightened British sensitivities to the potential outcomes of insurrection.

Some scholars, including Trinidadian historian Eric Williams, have claimed that with the emergence of capitalism, slavery was no longer profitable, and as such increased support for abolition beginning in the late 18th century.

After long and heated debates in Britain, the government agreed to compensate West Indian planters for shifting from slave to free labour, allotting £20 million for this purpose.

[6] The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 established a system of indentured servitude or "apprenticeship" that required freed slaves to continue to work for their former owners as apprentices.

[7] As stipulated in the emancipation act, field hands were apprenticed for a period of six years, household labourers were to work for four, and children under the age of six were immediately freed.

In return for unpaid labour, ex-slaves received food, housing, clothing and medical treatment from their employers though the Act did not specify precise quantities.

[6] The British government designated Crown-appointed magistrates to oversee the newly implemented labour system and these officials were tasked with protecting the interests of free people of color.

[9] Fearful of the response that conditional emancipation might elicit from former slaves, the colonial authorities created police districts to maintain societal order.

Widespread support for the use of treadmills also came from West Indian planters who were convinced that former slaves would not produce the same outputs if they were not adequately disciplined with corporal punishment.

In Trinidad, apprentices were granted a five-day work week, masters became required to care for freed children, and workers were compensated for labour performed on a Saturday.

Apprentices were appraised in the local courts and high prices hampered slaves' ability to free themselves, given their lack of access to material wealth, which was being systematically withheld from them.

The narrative played a critical role in the anti-apprenticeship campaign launched by Joseph Sturge and other members of Britain's Central Emancipation Committee.

While there, he and other anti-apprenticeship activists met James Williams, an apprentice from St. Ann's Parish that worked on the Penshurst Plantation for the Senior family, who shared his experience with the abolitionists.

Sturge organized to have his narrative recorded by an amanuensis and published it in hopes of informing the British public about Caribbean labour conditions and gaining widespread support for immediate abolition.

Throughout and in great detail, Williams explains how he was treated unfairly by his master and workhouse prisoners were tied to the treadmills, forced to "dance" on the machine after long days of labour and severely flogged.

Its narrow focus and centring of violence is likely a result of the narrative's political purpose and intended British audience and may suggest that abolitionists and the amanuensis who worked with Williams influenced what themes and details were included.

Yet, despite the emphasis on violence, Williams describes how he attempted to resist exploitation through truancy, theft and appealing to magistrates for protection against his masters' abuses.

The Jamaica Despatch, a pro-planter Jamaican newspaper, criticized James Williams and Joseph Sturge and insisted that the narrative was propaganda and its claims unfounded.

As a result, In 1837, after receiving and reviewing the publication, the Colonial Office tasked Sir Lionel Smith, the governor of Jamaica, to investigate the allegations made in Williams' narrative and to establish a commission to interview the apprentices, magistrates, and workhouse overseers in St. Ann's and other Jamaican parishes.

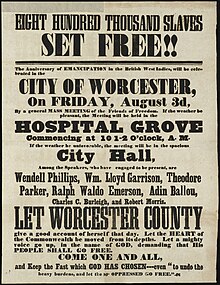

[8] Narrative of Events, other damaging accounts and investigations of the West Indian workhouses, local fears of rebellion and pressure from the British public led the colonial assemblies to prematurely abolish the apprenticeship system and all had done so by 1838.

They encouraged ex-slaves to legally marry, adopt the nuclear family model, and to take on Victorian gender roles which they believed were they path to achieving respectability and upward mobility.

[24] To some extent, freedmen and women embraced these gender conventions but some aspects of the patriarchal model were incompatible with their economic circumstances, personal preferences and understandings of kinship.

Historian Sheena Boa has suggested that because their mobility and choices were no longer controlled by outsiders, enjoyment of their own bodies was one way that freedmen and women "tested the limits of their freedom.

The aspiration to become independent cultivators and to grow food to support their families and to turn a profit was ubiquitous among the freed West Indians but their success in this endeavor varied.

Freed persons who occupied Crown land without authorization were expelled and their provision grounds, used for subsistence or to grow crops for sale, were sometimes burnt or confiscated.

[32] Attempts to shield themselves from sexual abuse, the prioritization of child rearing, poor experiences under apprenticeship and political protest may also explain women's exodus from wage cultivation.

[33] By the mid-19th century, just years after emancipation, the Caribbean's economy began to fail as a result of dropping sugar prices and planters in regions like Jamaica saw their plantations close down.