Embryology

Modern embryology developed from the work of Karl Ernst von Baer, though accurate observations had been made in Italy by anatomists such as Aldrovandi and Leonardo da Vinci in the Renaissance.

Much early embryology came from the work of the Italian anatomists Aldrovandi, Aranzio, Leonardo da Vinci, Marcello Malpighi, Gabriele Falloppio, Girolamo Cardano, Emilio Parisano, Fortunio Liceti, Stefano Lorenzini, Spallanzani, Enrico Sertoli, and Mauro Ruscóni.

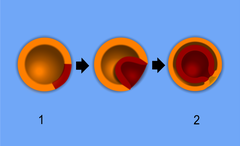

As microscopy improved during the 19th century, biologists could see that embryos took shape in a series of progressive steps, and epigenesis displaced preformation as the favored explanation among embryologists.

During gastrulation, the blastula develops in one of two ways that divide the whole animal kingdom into two-halves (see: Embryological origins of the mouth and anus).

In regard to humans, the term embryo refers to the ball of dividing cells from the moment the zygote implants itself in the uterus wall until the end of the eighth week after conception.

For decades, a number of so-called normal staging tables were produced for the embryology of particular species, mainly focussing on external developmental characters.

As of today, human embryology is taught as a cornerstone subject in medical schools, as well as in biology and zoology programs at both an undergraduate and graduate level.

Some scriptures state that it is active at conception, while others suggest that consciousness begins in the seventh to ninth month of fetal development.

[11][9] Many pre-Socratic philosophers are recorded as having opinions on different aspects of embryology, although there is some bias in the description of their views in later authors such as Aristotle.

Asclepiades agreed that men are formed within fifty days, but he believed that women took a full two months to be fully knit.

One observation, variously attributed to either Anaxagoras of Clazomenae or Alcmaeon of Croton, says that the milk produced by mammals is analogous to the white of fowl egg.

[12] Discussion on various views regarding how long it takes for specific parts of the embryo to form appear in an anonymous document known as the Nutriment.

Hippocrates claimed that the development of the embryo is put into motion by fire and that nourishment comes from food and breath introduced into the mother.

An outer layer of the embryo solidifies, and the fire within consumes humidity which makes way for development of bone and nerve.

This idea was derived from the observation that menstrual blood ceases during pregnancy, which Hippocrates took to imply that it was being redirected to fetal development.

Aristotle singularly wrote more on embryology than any other pre-modern author, and his influence on the subsequent discussion on the subject for many centuries was immense, introducing into the subject forms of classification, a comparative method from various animals, discussion of the development of sexual characteristics, compared the development of the embryo to mechanistic processes, and so forth.

[18] Next to Aristotle, the most impactful and important Greek writer on biology was Galen of Pergamum, and his works were transmitted throughout the Middle Ages.

Galen described processes that played a role in furthering development of the embryo such as warming, drying, cooling, and combinations thereof.

As this development plays out, the form of life of the embryo also moves from that like a plant to that of an animal (where the analogy between the root and umbilical cord is made).

In this time, then, the Roman practice of child exposure came to an end, where unwanted yet birthed children, usually females, were discarded by the parents to die.

The notion originating from the Greeks that the male embryo developed faster remained in various authors until it was experimentally disproven by Andreas Ottomar Goelicke in 1723.

[25] Various patristic literature from backgrounds ranging from Nestorian, Monophysite and Chalcedonian discuss and choose between three different conceptions on the relation between the soul and the embryo.

Based on Exodus 21:22 and Zachariah 12:1, the Monophysite Philoxenus of Mabbug claimed that the soul was created in the body forty days after conception.

Maximus the Confessor ridiculed the Aristotelian notion of the development of the soul on the basis that it would make humans parents of both plants and animals.

The text in the Book of Job relating to the fetus forming by analogy to the curdling of milk into cheese was cited in the Babylonian Talmud and in even greater detail in the Midrash: "When the womb of the woman is full of retained blood which then comes forth to the area of her menstruation, by the will of the Lord comes a drop of white-matter which falls into it: at once the embryo is created.

And finally, God himself was thought to provide the spirit and soul, facial expressions, capacity for hearing and vision, movement, comprehension, and intelligence.

Talmudic embryology, in various aspects, follows Greek discourses especially from Hippocrates and Aristotle, but in other areas, makes novel statements on the subject.

[17] Judaism allows assisted reproduction, such as IVF embryo transfer and maternal surrogacy, when the spermatozoon and oocyte originate from the respective husband and wife.

In the early 6th century, Sergius of Reshaina devoted himself to the translation of Greek medical texts into Syriac and became the most important figure in this process.

Anurshirvan founded a medical school in the southern Mesopotamian city of Gundeshapur, known as the Academy of Gondishapur, which also acted as a medium for the transmission, reception, and development of notions from Greek medicine.