Emigration

Refugees and asylum seekers in this sense are the most marginalized extreme cases of migration,[4] facing multiple hurdles in their journey and efforts to integrate into the new settings.

[5] Scholars in this sense have called for cross-sector engagement from businesses, non-governmental organizations, educational institutions, and other stakeholders within the receiving communities.

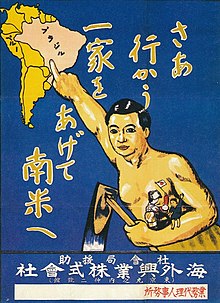

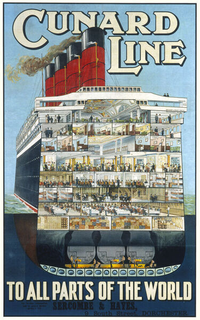

For instance, millions of individuals fled poverty, violence, and political turmoil in Europe to settle in the Americas and Oceania during the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.

[8] Motives to migrate can be either incentives attracting people away, known as pull factors, or circumstances encouraging a person to leave.

Diversity of push and pull factors inform management scholarship in their efforts to understand migrant movement.

[15] In Armenia, for example, the migration is calculated by counting people arriving or leaving the country via airplane, train, railway or other means of transportation.

In 1681, the emperor ordered construction of the Willow Palisade, a barrier beyond which the Chinese were prohibited from encroaching on Manchu and Mongol lands.

[21] Before 1950, over 15 million people emigrated from the Soviet-occupied eastern European countries and immigrated into the west in the five years immediately following World War II.

[26] In 1961, East Germany erected a barbed-wire barrier that would eventually be expanded through construction into the Berlin Wall, effectively closing the loophole.

[29] Other countries with tight emigration restrictions at one time or another included Angola, Egypt,[30] Ethiopia, Mozambique, Somalia, Afghanistan, Burma, Democratic Kampuchea (Cambodia from 1975 to 1979), Laos, North Vietnam, Iraq, South Yemen and Cuba.