Émilie du Châtelet

Her most recognized achievement is her translation of and her commentary on Isaac Newton's 1687 book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica containing basic laws of physics.

Her philosophical magnum opus, Institutions de Physique (Paris, 1740, first edition; Foundations of Physics), circulated widely, generated heated debates, and was republished and translated into several other languages within two years of its original publication.

[1] Du Châtelet participated in the famous vis viva debate, concerning the best way to measure the force of a body and the best means of thinking about conservation principles.

Posthumously, her ideas were heavily represented in the most famous text of the French Enlightenment, the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert, first published shortly after du Châtelet's death.

In addition to producing famous translations of works by authors such as Bernard Mandeville and Isaac Newton, du Châtelet wrote a number of significant philosophical essays, letters, and books that were well-known in her time.

Historical evidence indicates that her work had a very significant influence on the philosophical and scientific conversations of the 1730s and 1740s – in fact, she was famous and respected by the greatest thinkers of her time.

[2] Francesco Algarotti styled the dialogue of Il Newtonianismo per le dame based on conversations he observed between du Châtelet and Voltaire in Cirey.

[3] Correspondance by du Châtelet included that with renowned mathematicians such as Johann II Bernoulli and Leonhard Euler, early developers of calculus.

[5] Du Châtelet also had a half-sister, Michelle, born in 1686, of her father and Anne Bellinzani, an intelligent woman who was interested in astronomy and married to an important Parisian official.

At the time of du Châtelet's birth, her father held the position of the Principal Secretary and Introducer of Ambassadors to King Louis XIV.

Du Châtelet's father Louis-Nicolas, recognizing her early brilliance, arranged for Fontenelle to visit and talk about astronomy with her when she was 10 years old.

[9] Her mother, Gabrielle-Anne de Froulay, had been brought up in a convent, which was at that time the predominant educational institution available to French girls and women.

When she was small, her father arranged training for her in physical activities such as fencing and riding, and as she grew older, he brought tutors to the house for her.

As a wedding gift, her husband was made governor of Semur-en-Auxois in Burgundy by his father; the recently married couple moved there at the end of September 1725.

Initially, she was tutored in algebra and calculus by Moreau de Maupertuis, a member of the Academy of Sciences; although mathematics was not his forte, he had received a solid education from Johann Bernoulli, who also taught Leonhard Euler.

On one occasion at the Café Gradot, a place where men frequently gathered for intellectual discussion, she was politely ejected when she attempted to join one of her teachers.

[8] Du Châtelet invited Voltaire to live at her country house at Cirey in Haute-Marne, northeastern France, and he became her long-time companion.

[19] In a healthy competition, they both entered the 1738 Paris Academy prize contest on the nature of fire, since du Châtelet disagreed with Voltaire's essay.

[21] Du Châtelet's relationship with Voltaire caused her to give up most of her social life to become more involved with her study in mathematics with the teacher of Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis.

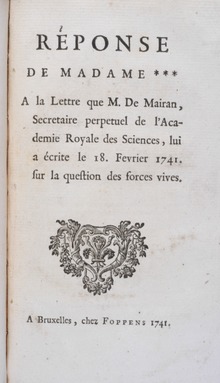

[32] Immanuel Kant's first publication in 1747, 'Thoughts on the True Estimation of Living Forces' (Gedanken zur wahren Schätzung der lebendigen Kräfte), focused on du Châtelet's pamphlet rebutting the arguments of the secretary of the French Academy of Sciences, Mairan.

[33] lnterestingly, Kant, in his Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime, wrote ad hominem and sexist critiques of learned women of the time, including Mme Du Châtelet, rather than writing about their work.

Dacier, or who conducts disputations about mechanics, like the Marquise du Châtelet might as well also wear a beard; for that might perhaps better express the mien of depth for which they strive.

Inspired by the theories of Gottfried Leibniz, she repeated and publicized an experiment originally devised by Willem 's Gravesande in which heavy balls were dropped from different heights into a sheet of soft clay.

[39] To undertake a formidable project such as this, du Châtelet prepared to translate the Principia by continuing her studies in analytic geometry, mastering calculus, and reading important works in experimental physics.

Her contributions in the French translation made Newton and his ideas look even better in the scientific community and around the world, and recognition for this is owed to du Châtelet.

To get from the possible or impossible to the actual or real, the principle of sufficient reason was revised by Du Châtelet from Leibniz's concept and integrated into science.

[9][43] To raise the money to pay back her debts, she devised an ingenious financing arrangement similar to modern derivatives, whereby she paid tax collectors a fairly low sum for the right to their future earnings (they were allowed to keep a portion of the taxes they collected for the King), and promised to pay the court gamblers part of these future earnings.

[44] Du Châtelet made a crucial scientific contribution in making Newton's historic work more accessible in a timely, accurate and insightful French translation, augmented by her own original concept of energy conservation.

In the early nineteenth century, a French pamphlet of celebrated women (Femmes célèbres) introduced a possibly apocryphal story of her childhood.

The Institut Émilie du Châtelet, which was founded in France in 2006, supports "the development and diffusion of research on women, sex, and gender".