Muslim Sicily

[1] It became a prosperous and influential commercial power in the Mediterranean,[2] with its capital of Palermo[note 2] serving as a major cultural and political center of the Muslim world.

[3] Sicily was a peripheral part of the Byzantine Empire when Muslim forces from Ifriqiya (roughly present-day Tunisia) began launching raids in 652.

During the reign of the Aghlabid dynasty in Ifriqiya, a prolonged series of conflicts from 827 to 902 resulted in the gradual conquest of the entire island, with only the stronghold of Rometta, in the far northeast, holding out until 965.

Under Muslim rule, Sicily became multiconfessional and multilingual, developing a distinct Arab-Byzantine culture that combined elements of its Islamic Arab and Berber migrants with those of the local Latin, Greek, and Jewish communities.

Lucrative new crops were introduced, advanced irrigation systems were built, and urban centers were beautified with gardens and public works; the resulting wealth led to a flourishing of art and science.

But by the mid thirteenth century, Muslims who had not already left or converted to Christianity were expelled, ending roughly four hundred years of Islamic presence in Sicily.

Over a period of twenty five years, the caliphate succeeded in annexing much of the Persian Sasanian Empire and former Roman territories in the Levant and North Africa.

[citation needed] By the end of the seventh century, with the Umayyad conquest of North Africa, the Muslims had captured the nearby port city of Carthage, allowing them to build shipyards and a permanent base from which to launch more sustained attacks.

[citation needed] The first true attempt at conquest was launched in 740; in that year the Muslim prince Habib, who had participated in the 728 attack, successfully captured Syracuse.

Emperor Michael II caught wind of the matter and ordered that General Constantine end the marriage and cut off Euphemius' nose.

[1] Reinforced by the Muslims, Euphemius' ships landed at Mazara del Vallo, where the first battle against loyalist Byzantine troops occurred on July 15, 827, resulting in an Aghlabid victory.

After year-long siege, and an attempted mutiny, his troops were able to defeat a large army sent from Palermo, backed by a Venetian fleet led by Doge Giustiniano Participazio.

They later renewed their offensive, but failed to conquer Castrogiovanni (modern Enna) where Euphemius was killed, forcing them to retreat back to their stronghold at Mazara.

The Iberian Muslims defeated the Byzantine commander Teodotus between July and August of that year, but again a plague forced them to return to Mazara and later Ifriqiya.

[16] The first years of Fatimid rule after 909 were difficult, as the Sicilian Muslims had already begun to acquire a distinct identity and they resisted attempts by new outsiders to assert themselves.

[22] It was only after this move to Egypt that the Fatimid caliphs implicitly recognized the Kalbids as hereditary rulers, who thenceforth governed the island as amirs on their behalf.

Raids into Southern Italy continued under the Kalbids into the 11th century, and in 982 a joint Christian army under the Emperor Otto II and the brothers Landulf and Pandulf was defeated at Stilo near Crotone in Calabria.

[28] The Norman Robert Guiscard, son of Tancred, then conquered Sicily in 1060 after taking Apulia and Calabria, while his brother Roger de Hauteville occupied Messina with an army of 700 knights.

Then in 1068, Roger and his men defeated Ayyub at the Battle of Misilmeri, and the Zirids returned to North Africa, leaving Sicily in disarray.

After the conquest of Sicily, the Normans removed the local emir, Yusuf Ibn Abdallah from power, while respecting the customs of the resident Arabs.

The Arabs further improved irrigation systems through Qanats and introduced new and lucrative crops, including oranges, lemons, pistachio and sugarcane.

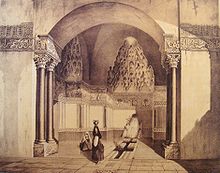

A walled suburb called the Kasr (the palace) is the center of Palermo until today, with the great Friday Mosque on the site of the later Roman cathedral.

[36] Arab traveler, geographer, and poet Ibn Jubair visited the area in the end of the 12th century and described Al-Kasr and Al-Khalisa (Kalsa): The capital is endowed with two gifts, splendor and wealth.

Seated in what is now the Royal Palace in Palermo, the emir held authority over most affairs of state, including the army, administration, justice, and the treasury.

He appointed the governors of major cities, high ranking judges (qāḍī), and arbitrators for minor disputes between individuals (hakam).

An assembly of notables called giamà'a played a consultative role, albeit sometimes making important decisions in lieu of the emir.

It is also very likely that the authorities operated a tiraz, an official workshop that produced valuable fabrics such as silk, which were granted as a sign of appreciation to their subject or as a gift to foreign dignitaries.

Western Sicily was more Islamized and heavily populated by Arabs, allowing for full and direct administration; by contrast, the northeast region of Val Demone remained majority Christian and often resistant to Muslim rule, prompting a focus on tax collection and maintaining public order.

The fighters or junud in conquering the lands obtained four-fifths as booty (fai) and one fifth was reserved for the state or the local governor (the khums), following the rules of Islamic law.

[45][46] The Norman rulers followed a policy of steady Latinization by bringing in thousands of Italian settlers from the northwest and south of Italy, and some others from southeast France.