Grand Duchy of Tuscany

His descendants ruled, and resided in, the grand duchy until its end in 1859, barring one interruption, when Napoleon Bonaparte gave Tuscany to the House of Bourbon-Parma (Kingdom of Etruria, 1801–1807), then annexed it directly to the First French Empire.

Despite all of these incentives to economic growth and prosperity, the population of Florence, at dawn of the 17th century, was a mere 75,000 souls, far smaller than the other capitals of Italy: Rome, Milan, Venice, Palermo and Naples.

Christina heavily relied on priests as advisors, lifting Cosimo I's ban on clergy holding administrative roles in government, and promoted monasticism.

[28] In 1657, Leopoldo de' Medici, the Grand Duke's youngest brother, established the Accademia del Cimento, which set up to attract scientists from all over Tuscany to Florence for mutual study.

Francesco de' Medici, Mattias de'Medici, and Ottavio Piccolomini (an Imperial general of Sienese origin) were among the ringleaders in the plot to assassinate field marshal Albrecht von Wallenstein, for which they were rewarded with spoils by Emperor Ferdinand II.

[42] Europe heard of the perils of Tuscany, and Joseph I, Holy Roman Emperor asserted a remote claim to the grand duchy (through some Medici descent), but died before he could press the matter.

[7] The plan was about to be approved by the powers convened at Geertruidenberg when Cosimo abruptly added that if himself and his two sons predeceased his daughter, the Electress Palatine, she should succeed and the republic be re-instituted following her death.

Gian Gastone for most of his life, kept to his bed and acted in an unregal manner, rarely appearing to his subjects, to the extent that, at times, he had been thought dead.

He capitulated to foreign demands, and instead of endorsing the claim to the throne of his closest male relative, the Prince of Ottajano, he allowed Tuscany to be bestowed upon Don Carlos.

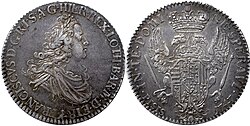

Francis had to cede his ancestral Duchy of Lorraine in order to accommodate the deposed ruler of Poland, whose daughter Marie Leszczyńska was Queen of France.

He died at Innsbruck from a stroke in 1765; his wife pledged the rest of her life to mourning him, while co-ruling with her first son, her own heir apparent, and Francis' imperial successor Joseph II.

[49] In 1763, when nuptial agreements for the marriage of the imperial couple's second surviving son, Leopold, and the Infanta of Spain, Maria Luisa of Bourbon, were stipulated, Tuscany was erected into a secundogeniture.

Chiarugi and his collaborators introduced new humanitarian regulations in the running of the hospital and caring for the mentally ill patients, including banning the use of chains and physical punishment, and in so doing have been recognized as early pioneers of what later came to be known as the moral treatment movement.

In 1790, Emperor Joseph II died without issue before carrying out his project for the abolition of secundogeniture in Tuscany, partly due to Leopold's latent resistance.

Thus, when the latter was called to Vienna, to assume the rule of his family's Austrian dominions and become Emperor,[52] his second-born son Ferdinand immediately succeeded him as head of the Grand Duchy.

Following the serious Sanfedist disorders that occurred in Tuscany upon Leopold's departure for Austria, the new emperor partially revoked the abolition of the death penalty ordered 4 years earlier, and in 1795 Ferdinand further expanded the scope of its application.

[55][56] The Napoleonic system collapsed in 1814, and the following territorial settlement agreed to at the Congress of Vienna, ceded the State of Presidi and the Principality of Piombino to a restored Tuscany.

In 1847, in application of the 1844 secret Treaty of Florence [it], Leopold II annexed the Duchy of Lucca, a state created by the Congress of Vienna solely to accommodate the House of Bourbon-Parma until they could re-assume their Parmese sovereignty upon the death of the Duchess of Parma for life, Marie Louise of Austria.

On taking possession of his new state, Leopold unexpectedly granted it the abolition of the death penalty, a measure whose effectiveness the supreme court of Florence hastened to extend to the entire territory of the Grand Duchy, at the beginning of 1848.

Strongly attached to its ideal traditions, it remained the only region in Italy to maintain the abolition of capital punishment in force until 1889, when it was eventually extended to the whole Kingdom with the promulgation of the new Zanardelli penal code.

The Senate, composed of forty-eight men, chosen by the constitutional reform commission, was vested with the prerogative of determining Florence's financial, security, and foreign policies.

[67] Over time, the Medici acquired several territories, which included: the County of Pitigliano, purchased from the Orsini family in 1604; the County of Santa Fiora, acquired from the House of Sforza in 1633; Spain ceded Pontremoli in 1650, Silvia Piccolomini sold her estates, the Marquisate of Castiglione at the time of Cosimo I, Lordship of Pietra Santa, and the Duchy of Capistrano and the city of Penna in the Kingdom of Naples.

For the decades thereafter, the grand dukes only maintained a peacetime force of 2,500 soldiers, 500 cavalry to patrol the coasts and 2,000 infantry to man castles (Cosimo I having significantly expanded Tuscany's fortification network in an effort to defend the country).

[72] A Tuscan-Spanish treaty that bound the two at the end of the Italian Wars demanded that Tuscany send 5,000 troops to the Spanish army if ever the Duchy of Milan or Naples was attacked.

In 1613, Cosimo II sent 2,000 infantry and 300 cavalry, along with an undisclosed number of Tuscan adventurers, to aid the Spanish after Savoy launched an invasion of the Duchy of Montferrat.

[69] Tuscany's economic and military strength cratered from the second half of the 17th century onward, which was reflected in the quality of its army; by 1740 it only consisted of a few thousand poorly-trained men and was considered impotent to such a degree that its Habsburgs rulers allowed enemy troops to cross the duchy unopposed.

In 1572 the Tuscan navy consisted of 11 galleys, 2 galleasses, 2 galleons, 6 frigates, and various transports, carrying in all 200 guns, manned by 100 knights, 900 seamen, and 2,500 oarsmen.

Grand Duke Ferdinand I sought to expand Tuscany's naval strength during his reign, and cooperated with the Order of Saint Stephen, which often blurred the line between itself and the Tuscan navy.

In 1608, they intercepted a Turkish convoy of 42 vessels off Rhodes, seizing 9 and netting 600 slaves and a booty of 1 million ducats, equivalent to two years of revenue for the whole grand duchy.

A notable incident in this time was a naval battle off Sardinia in October 1624, in which 15 Tuscan, Papal, and Neapolitan galleys converged on a flotilla of 5 Algerian pirate vessels (including a large flagship).