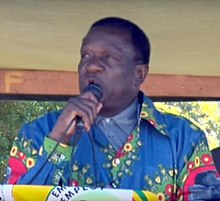

Emmerson Mnangagwa

[12][16][19] Although his course at Kafue was supposed to last three years, in 1959 Mnangagwa decided to leave early and attend Hodgson Technical College, one of the country's leading educational institutions.

[12][21] In August 1963, ten of the 13 trainees, including Mnangagwa, joined the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), which had been formed earlier that month as a breakaway group from ZAPU.

[12] After arriving in Tanganyika in late August 1963, six of the eleven returned to Southern Rhodesia, while the other five, including Mnangagwa, were sent to briefly stay at a training camp in Bagamoyo run by FRELIMO, the group seeking to liberate Mozambique from Portuguese rule.

[22] Part of the first group of ZANLA fighters sent overseas for training, he and four others were sent to Beijing, where he spent the first two months studying at Peking University's School of Marxism, run by the Chinese Communist Party.

[26] Upon returning to Tanzania, Mnangagwa co-founded the Crocodile Gang, a ZANLA guerrilla unit led by William Ndangana composed of the men he had trained within China: John Chigaba, Robert Garachani, Lloyd Gundu, Felix Santana, and Phebion Shonhiwa.

[12][30] Shortly after the congress, three members of the Crocodile Gang were captured and arrested for smuggling guns into the country, while Lawrence Svosve went missing after being sent by Mnangagwa to Lusaka to retrieve some messages.

[12] Soon, party leaders at Sikombela sent the group a message urging them to take more extreme actions as a means of gaining publicity, with the hope that greater exposure would bring ZANU's efforts to the attention of the Organisation of African Unity's Liberation Committee, which was meeting in Dar es Salaam at the time.

[12] The Crocodile Gang, now comprising Ndangana, Malowa, Victor Mlambo, James Dhlamini, Master Tresha, and Mnangagwa, met to make plans at Ndabaningi Sithole's house in the Highfield suburb of Salisbury.

[12] On 4 July 1964, the Crocodile Gang ambushed and murdered Pieter Johan Andries Oberholzer, a white factory foreman and police reservist, in Melsetter, near Southern Rhodesia's eastern border.

[12][31] At Khami, he was given the number 841/66 and classified as "D" class, reserved for those considered most dangerous, and was held with other political prisoners, whom the government kept in a separate block of cells away from other inmates out of fear that they would influence them ideologically.

[34] Mnangagwa was discharged from Khami on 6 January 1972 and transferred back to Salisbury Central Prison, where he was detained alongside other revolutionaries, including Mugabe, Nkala, Nyagumbo, Tekere and Didymus Mutasa.

[12] In 1979, Mnangagwa accompanied Mugabe to the negotiations in London that led to the signing of the Lancaster House Agreement, which brought an end to Rhodesia's unrecognised independence and ushered in majority rule.

[40] After the head of Zimbabwe Defence Forces, the Rhodesian holdover general Peter Walls, was dismissed by Mugabe on 15 September 1980, Mnangagwa also took over as Chairman of the Joint Operations Command.

[53] In the late 1980s, a series of court cases exposed the existence of apartheid South African spies within the CIO, who played a significant role in causing the Gukurahundi by providing distorted intelligence reports and purposely inflaming ethnic tensions.

[54] Another, Matt Calloway, formerly the CIO's top agent in Hwange District, was in 1983 identified by the Zimbabwean government as being involved a South African operation that recruited, trained, and armed disaffected Ndebeles and sent them back into Matabeleland as guerrillas.

[42][25] According to a 1988 report by the U.S. embassy in Harare, Mugabe originally intended to name Mnangagwa Minister of Defence, but was persuaded not to by Nathan Shamuyarira and Sydney Sekeramayi, the leaders of the "Group of 26", a clique that sought to increase the political power of members of the Zezuru people, a Shona subgroup.

[55] However, there were also reports of voter intimidation and harassment, including from Women's League members, some of whom said they were coerced into joining a demonstration against the Zimbabwe Unity Movement, the opposition party contesting Mnangagwa's seat.

[67] In 2002, a report authored by a panel commissioned by the UN Security Council implicated him in the exploitation of mineral wealth from the Congo and for his involvement in making Harare a significant illicit diamond trading centre.

[38] The controversy began when Moyo hosted a meeting with other politicians in his home district of Tsholotsho to discuss replacing Mugabe's choice for vice-president, Joice Mujuru, with Mnangagwa.

[62][71][72] Mnangagwa attempted to distance himself from the controversy, but nevertheless lost his title as ZANU–PF's secretary for administration, an office he had held for four years and one that gave him the power to appoint his allies to important party positions.

[23][86][87] Despite having coordinated a campaign of political violence against the MDC–T in 2008, and allegedly having been behind three separate attempts to assassinate Tsvangirai over the years, Mnangagwa spoke kindly about the country's coalition government in a 2011 interview.

[91] His appointment followed the dismissal of Mnangagwa's long-time opponent in the succession rivalry, Joice Mujuru, who was cast into the political wilderness amidst allegations that she had plotted against Mugabe.

[98] The programme, which Mnangagwa said would receive US$500 million in funding, would involve 2,000 maize-growing small-scale and commercial farmers and would allow the government to determine how much maize is grown and the price at which it is sold.

[8] Mnangagwa drew his support from war veterans and the country's military establishment, in part because of his past leadership of the Joint Operations Command, as well as his reputation in Zimbabwe as a cultivator of stability.

"[108][109] The First Lady further accused Mnangagwa, or his allies, of trying to bomb her dairy farm (in fact, several army officers and fringe political activists were charged with the crime), and suggested that his supporters were behind a plot to murder her son.

"[115] Following the incident, rumors spread among supporters of Mnangagwa that Grace Mugabe had ordered the vice-president's poisoning via ice cream produced at a dairy farm she controlled.

[117] That statement, coupled with President Mugabe's announcement several days later that he planned to review the performance of his ministers, led to speculation that a cabinet reshuffle could result in an unfavorable outcome for Mnangagwa.

[142] On 3 March 2021, newly inaugurated President Joe Biden of the United States issued a statement that criticizes Mnangagwa for violent repressions of citizens and lack of democratic reforms, authorizing an extension of US sanctions on Zimbabwe through a US national emergency declared in Executive Order 13288.

[152] In January 2019, Mnangagwa announced fuel prices would be raised by 130% in an attempt to stop oil smuggling activities where offenders would buy petrol and transport it to surrounding countries.

[157] Mnangagwa has, since the early 1990s, played a key role in implementing the "Indigenisation and Black Economic Empowerment" initiative, as advised by prominent indigenous businessmen including Ben Mucheche, John Mapondera, Paul Tangi Mhova Mkondo, and the think tank and lobby group IBDC.