Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor

Based on an enormous ransom for the release and submission of King Richard I of England, he conquered Sicily in 1194; however, the intended unification with the Holy Roman Empire ultimately failed due to the opposition of the Papacy.

[2][3] Henry threatened to invade the Byzantine Empire after 1194 and succeeded in extracting a ransom, the Alamanikon, from Emperor Alexios III Angelos in return for cancelling the invasion.

Henry was fluent in Latin and, according to the chronicler Alberic of Trois-Fontaines, was "distinguished by gifts of knowledge, wreathed in flowers of eloquence, and learned in canon and Roman law".

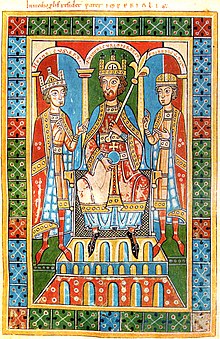

According to his rank and with Imperial Eagle (Reichsadler), regalia, and a scroll, he is the first and foremost to be portrayed in the famous Codex Manesse, a 14th-century songbook manuscript featuring 140 reputed poets; at least three poems are attributed to a young and romantically minded Henry VI.

[8] In the Hohenstaufen conflict with Pope Urban III, Henry moved to the March of Tuscany, and with the aid of his deputy Markward von Annweiler devastated the adjacent territory of the Papal States.

Further difficulties arose when the exiled Welf duke Henry the Lion returned from England and began to subdue large estates in his former Duchy of Saxony.

To assert his own rights in the inheritance dispute, Henry initially supported Tancred's rival Count Roger of Andria and made arrangements for a campaign to Italy.

The next year he concluded a peace agreement with Henry the Lion at Fulda and moved farther southwards to Augsburg, where he learned that his father had died on crusade attempting to cross the Saleph River near Seleucia in the Kingdom of Cilicia (now part of Turkey) on 10 June 1190.

He further had to arbitrate in a conflict in the Margraviate of Meissen on the eastern border of the Empire, where the Wettin margrave Albert I had to fend off the claims raised by his brother Theoderic and Landgrave Hermann of Thuringia.

[9] At this stage, Henry had a stroke of good fortune when the Babenberg duke Leopold V of Austria gave him his prominent prisoner, Richard the Lionheart, King of England, whom he had captured on his way back from the Third Crusade and held at Dürnstein Castle.

Ignoring his near excommunication by Pope Celestine III for imprisoning a former crusader, he held the English King for a ransom of 150,000 silver marks and officially declared a dowry of Richard's niece Eleanor, who was to marry Duke Leopold's son Frederick.

In turn the emperor under threat of military violence demanded the restitution of the French lands, which John had seized upon approval by Philip during Richard's absence.

He and Richard ceremoniously reconciled at the Hoftag in Speyer during Holy Week 1194: the English king publicly regretted any hostilities, genuflected, and cast himself on the emperor's mercy.

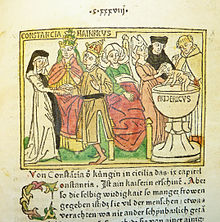

On the next day his wife Constance, who had stayed back in Iesi, gave birth to his only son and heir Frederick II, the future emperor and king of Sicily and Jerusalem.

[9] The young William and his mother Sibylla had fled to Caltabellotta Castle; he officially renounced the Sicilian kingdom in turn for the County of Lecce and the Principality of Capua.

His loyal henchman Markward von Annweiler was appointed a duke of Ravenna, placing him in a highly strategic position to control the route to Sicily via the Italian Romagna region and the Apennines.

In 1195 Henry's envoys in Constantinople raised claims to former Italo-Norman possessions around Dyrrachium (Durrës), one of the most important naval bases on the eastern Adriatic coast, and pressed for a contribution to the planned crusade.

He already evolved plans to betroth his younger brother Philip to Isaac's daughter Princess Irene Angelina—deliberately or not—opening up a perspective to unite the Western and Eastern Empire under Hohenstaufen rule.

According to the contemporary historian Niketas Choniates his legates were able to collect a large tribute from Isaac's brother and successor Alexios III but it was not paid before Henry's death.

[15] When an armistice between Pisa and the Republic of Venice ended, the Pisans attacked Venetian ships in Marmora and carried out raids against theỉr premises in Constantinople.

In October he reconciled with Archbishop Hartwig of Bremen at Gelnhausen and was able to obtain the support of numerous Saxon and Thuringian nobles for his crusade which was scheduled to begin on Christmas 1196.

Though they would have lost their right to elect the kings, the secular princes themselves wished to make their Imperial fiefs hereditary and to be inheritable by the female line as well, and Henry agreed to consider these demands.

The emperor also bought the support of ecclesiastical princes by announcing that he would be willing to give up the Jus Spolii and the right to receive recurring earnings from church lands during a period of sede vacante.

At the same time, the emperor stayed in Capua, where he had Count Richard of Acerra, held in custody by his ministerialis Dipold von Schweinspeunt, cruelly executed.

Soon after, the transition to Hohenstaufen's rule in Italy spurred revolts, especially around Catania and southern Sicily, which his German soldiers led by Markward of Annweiler and Henry of Kalden suppressed mercilessly.

Some contemporary Germans (who were hostile to Empress Constance) even accused her of directly collaborating with the rebels, even though recent research like the work of Theo Kölzer shows that this was unlikely.

[25] In the midst of preparations Henry fell ill with chills while hunting near Fiumedinisi and on 28 September died, likely of malaria (contracted since the siege of Napoli in 1191 and had never completely healed), in Messina,[26] although some immediately accused Constance of poisoning him.

The German throne quarrel lasted nearly twenty years, until Frederick was again elected king in 1212 and Otto, defeated by the French in the 1214 Battle of Bouvines and abandoned by his former allies, finally died in 1218.

Several contemporary accounts of his life given by ecclesiastical chroniclers like Godfrey of Viterbo or Peter of Eboli in his Liber ad honorem Augusti (on the emperor's conquest of Sicily) paint a bright picture of Henry's rule; while the annals by Otto of Sankt Blasien are considered more objective.

[29][30] Later historians stressed the fact of Henry's early death and the succeeding throne quarrel as a stroke of fate and a major setback for the development of a German nation state begun under his father Frederick Barbarossa.