Philip II of Spain

In 1588, he sent an armada to invade Protestant England, with the strategic aim of overthrowing Elizabeth I and re-establishing Catholicism there, but his fleet was defeated in a skirmish at Gravelines (northern France) and then destroyed by storms as it circled the British Isles to return to Spain.

Philip was also close to his two sisters, María and Juana, and to his two pages, the Portuguese nobleman Rui Gomes da Silva and Luis de Requesens y Zúñiga, the son of his governor.

The newest constituent kingdom in the empire was Upper Navarre, a realm invaded by Ferdinand II of Aragon mainly with Castilian troops (1512), and annexed to Castile with an ambiguous status (1513).

In November 1592, the Parliament (Cortes) of Aragón revolted against another breach of the realm-specific laws, so the Attorney General (Justicia) of the kingdom, Juan de Lanuza, was executed on Philip II's orders, with his secretary Antonio Pérez taking exile in France.

[14] Aside from reducing state revenues for overseas expeditions, the domestic policies of Philip II further burdened the Spanish kingdoms and would, in the following century, contribute to its decline, as maintained by some historians.

The lack of a viable supreme assembly led to power defaulting into Philip II's hands, especially as manager and final arbiter of the constant conflict between different authorities.

Earlier, however, after several setbacks in his reign and especially that of his father, Philip did achieve a decisive victory against the Turks at Lepanto in 1571, with the allied fleet of the Holy League, which he had put under the command of his illegitimate brother, John of Austria.

Charles V abdicated the throne of Naples to Philip on 25 July 1554, and the young king was invested with the kingdom (officially a Papal fief) on 2 October by Pope Julius III.

In a letter to the Princess Dowager of Portugal, Regent of the Spanish kingdoms, dated 22 September 1556, Francisco de Vargas wrote: I have reported to your Highness what has been happening here, and how far the Pope is going in his fury and vain imaginings.

I am sure your Highness will have had more recent news from the Duke of Alva, who has taken the field with an excellent army and has penetrated so far into the Pope's territory that his cavalry is raiding up to ten miles from Rome, where there is such panic that the population would have run away had not the gates been closed.

It marked also the beginning of a period of peace between the Pope and Philip, as their European interests converged, although political differences remained and diplomatic contrasts eventually re-emerged.

He directly intervened in the final phases of the wars (1589–1598), ordering Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma into France in an effort to unseat Henry IV, and perhaps dreaming of placing his favourite daughter, Isabella Clara Eugenia, on the French throne.

The 1598 Treaty of Vervins was largely a restatement of the 1559 Peace of Câteau-Cambrésis and Spanish forces and subsidies were withdrawn; meanwhile, Henry issued the Edict of Nantes, which offered a high degree of religious toleration for French Protestants.

[29] Philip II's inaction despite repeated pleas by Sarmiento to aid the ailing colony has been attributed to the strain on Spain's resources that resulted from wars with England and Dutch rebels.

[37] In 1572, a prominent exiled member of the Dutch aristocracy, William the Silent, Prince of Orange, invaded the Netherlands with a Protestant army, but he only succeeded in holding two provinces, Holland and Zeeland.

Because of the Spanish repulse in the Siege of Alkmaar (1573) led by his equally brutal son Fadrique,[37] Alba resigned his command, replaced by Luis de Requesens y Zúñiga.

In 1584, William the Silent was assassinated by Balthasar Gérard, after Philip had offered a reward of 25,000 crowns to anyone who killed him, calling him a "pest on the whole of Christianity and the enemy of the human race".

When Henry died two years after Sebastian's disappearance, three grandchildren of Manuel I claimed the throne: Infanta Catarina, Duchess of Braganza; António, Prior of Crato; and Philip II of Spain.

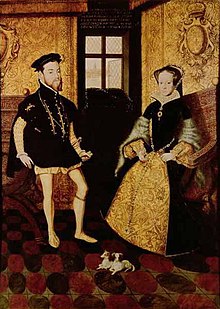

The Privy Council instructed that Philip and Mary should be joint signatories of royal documents, and this was enacted by an Act of Parliament, which gave him the title of king and stated that he "shall aid her Highness ... in the happy administration of her Grace's realms and dominions".

Philip's great-grandson, Philippe I, Duke of Orléans, married Princess Henrietta of England in 1661; in 1807, the Jacobite claim to the British throne passed to the descendants of their child Anne Marie d'Orléans.

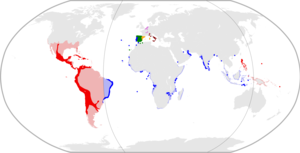

However, in spite of the great and increasing quantities of gold and silver flowing into his coffers from the American mines, the riches of the Portuguese spice trade, and the enthusiastic support of the Habsburg dominions for the Counter-Reformation, he would never succeed in suppressing Protestantism or defeating the Dutch rebellion.

He was a devout Catholic and exhibited the typical 16th century antipathy for religious heterodoxy; he said, "Before suffering the slightest damage to religion in the service of God, I would lose all of my estates and a hundred lives, if I had them, because I do not wish nor do I desire to be the ruler of heretics.

[65] Even before his death in 1598, his supporters had started presenting him as an archetypical gentleman, full of piety and Christian virtues, whereas his enemies depicted him as a fanatical and despotic monster, responsible for inhuman cruelties and barbarism.

[68] That way, the popular image of the King that survives to today was created on the eve of his death, at a time when many European princes and religious leaders were turned against Spain as a pillar of the Counter-Reformation.

In a more recent example of popular culture, Philip II's portrayal in Fire Over England (1937) is not entirely unsympathetic; he is shown as a very hardworking, intelligent, religious, somewhat paranoid ruler whose prime concern is his country, but who had no understanding of the English, despite his former co-monarchy there.

Even in countries that remained Catholic, primarily France and the Italian states, fear and envy of Spanish success and domination created a wide receptiveness for the worst possible descriptions of Philip II.

He succeeded in increasing the importation of silver in the face of English, Dutch, and French privateers, overcoming multiple financial crises and consolidating Spain's overseas empire.

Historian Geoffrey Parker offers a management-psychological explanation, as summarized by Tonio Andrade and William Reger: One might have expected that Philip—being a dedicated, persistent, and hard-working man, and being the head of Western Europe's wealthiest and largest empire—would have succeeded in his aims.

[77] His coinage typically bore the obverse inscription "PHS·D:G·HISP·Z·REX" (Latin: "Philip, by the grace of God King of Spain et cetera"), followed by the local title of the mint ("DVX·BRA" for Duke of Brabant, "C·HOL" for Count of Holland, "D·TRS·ISSV" for Lord of Overissel, etc.).

Pope Pius V initially refused to grant Philip the dispensation needed to marry Anna, citing biblical prohibitions and the danger of birth defects.