United Kingdom employment equality law

As an integral part of UK labour law it is unlawful to discriminate against a person because they have one of the "protected characteristics", which are, age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, race, religion or belief, sex, pregnancy and maternity, and sexual orientation.

[1] Discrimination is unlawful when an employer is hiring a person, in the terms and conditions of contract that are offered, in making a decision to dismiss a worker, or any other kind of detriment.

"Direct discrimination", which means treating a person less favourably than another who lacks the protected characteristic, is always unjustified and unlawful, with the exception of age.

"Indirect discrimination" is also unlawful, and this exists when an employer applies a policy to their workplace that affects everyone equally, but it has a disparate impact on a greater proportion of people of one group with a protected characteristic than another, and there is no good business justification for that practice.

Any dismissal because of discrimination is automatically unfair and entitles a person to claim under the Employment Rights Act 1996 section 94 no matter how long they have worked.

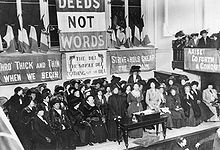

"[2]The Representation of the People Act 1918 gave the universal franchise to men, and knocked away the last barriers of wealth discrimination for the vote.

In Roberts v Hopwood (1925) a metropolitan borough council had decided to pay its workers a minimum of £4 a week, whether they were men or women and regardless of the job they did.

Lord Atkinson said "the council would, in my view, fail in their duty if ... [they] allowed themselves to be guided in preference by some eccentric principles of socialistic philanthropy, or by a feminist ambition to secure the equality of the sexes in the matter of wages in the world of labour.

"[4] Though Lord Buckmaster said "Had they stated that they determined as a borough council to pay the same wage for the same work without regard to the sex or condition of the person who performed it, I should have found it difficult to say that that was not a proper exercise of their discretion.

Its basic purpose was "… to amend the Law with respect to disqualification on account of sex" "from the exercise of any public function, or from being appointed to or holding any civil or judicial office or post, or from entering or assuming or carrying on any civil profession or vocation, or for admission to any incorporated society (whether incorporated by Royal Charter or otherwise)".

As Britain's colonies won independence, many immigrated to the motherland, and for the first time communities of all colours were seen in London and the industrial cities of the North.

The Conservative government opted out of the Social Chapter of the treaty, which included provisions on which anti-discrimination law would be based.

Although they passed the Disability Discrimination Act 1995, it was not until Tony Blair's "New Labour" government won the 1997 election that the UK opted into the social provisions of EU law.

Particularly since the United Kingdom joined the Social Chapter of the European Union treaties, it mirrors a series of EU Directives.

If the workforce does not reflect society's makeup (e.g. that women, or ethnic minorities are under-represented) then the employer may prefer the candidate which would correct that imbalance.

Section 159, which deals with positive action in connection with recruitment and promotion (and which is the basis for the example of equally qualified applicants above), did not come into force until April 2011.

[10] Section 158 deals with the circumstances in which positive action is permitted other than in connection with recruitment and promotion, for example in provision of training opportunities.

[12] Section 15 Equality Act 2010 creates a broad protection against being treated unfavourably "because of something arising in consequence of" the person's disability, but subject to the employer having an 'objective justification' defence if it shows its action was a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

The duty can apply where a disabled person is put at a 'substantial' disadvantage in comparison with non-disabled people by a 'provision, criterion or practice' or by a physical feature.

A further strand of the duty can require an employer to provide an auxiliary aid or service (s 20(5) Equality Act 2010).

For people with religious sensitivities, particularly the desire to worship during work cases show there is no duty, but employers should apply their minds to accommodating their employee's wishes even if they ultimately decide not to.

For lawyers, the most important work of predecessors has been strategic litigation[13] (advising and funding cases which could significantly advance the law) and developing codes of best practice for employers to use.

Beliefs often lead adherents to the need to manifest their closely held views, in a way which may conflict with ordinary requirements of the work place.

More recently, two measures have been introduced, and one has been proposed, to prohibit discrimination in employment based on atypical work patterns, for employees who are not considered permanent.

Discrimination against union members is also a serious problem, for the obvious reason that some employers view unionisation as threat to their right to manage.