Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

After months spent in makeshift camps as the ice continued its northwards drift, the party used lifeboats that had been salvaged from the ship to reach the inhospitable, uninhabited Elephant Island.

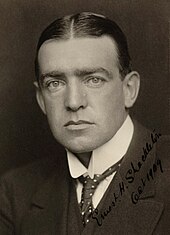

Despite the public acclaim that had greeted Ernest Shackleton's achievements after the Nimrod Expedition in 1907–1909, the explorer was unsettled, becoming—in the words of British skiing pioneer Sir Harry Brittain—"a bit of a floating gent".

This group, with 69 dogs, two motor sledges, and equipment "embodying everything that the experience of the leader and his expert advisers can suggest",[14] would undertake the 1,800-mile (2,900 km) journey to the Ross Sea.

[15] The Royal Geographical Society (RGS), from which he had expected nothing, gave him £1,000—according to Huntford, Shackleton, in a grand gesture, advised them that he would only need to take up half of this sum.

[24][25] Shackleton received more than 5,000 applications for places on the expedition, including a letter from "three sporty girls" who suggested that if their feminine garb was inconvenient they would "just love to don masculine attire.

"[26] Eventually the crews for the two arms of the expedition were trimmed down to 28 apiece, including William Bakewell, who joined the ship in Buenos Aires; his friend Perce Blackborow, who stowed away when his application was turned down;[27] and several last-minute appointments made to the Ross Sea party in Australia.

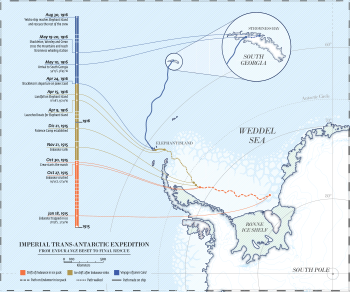

[42] Further delays then slowed progress after the turn of the year, before a lengthy run south during 7–10 January 1915 brought them close to the 100-foot (30 m) ice walls which guarded the Antarctic coastal region of Coats Land.

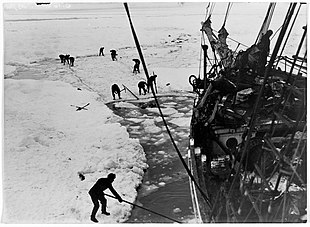

[45] Strenuous efforts were made to release her; on 14 February, Shackleton ordered men onto the ice with ice-chisels, prickers, saws and picks to try to force a passage, but the labour proved futile.

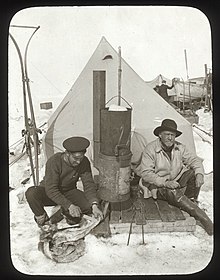

The dogs were taken off board and housed in ice-kennels or "dogloos", and the ship's interior was converted to suitable winter quarters for the various groups of men—officers, scientists, engineers, and seamen.

It would be at least four months before spring brought the chance of an opening of the ice, and there was no certainty that Endurance would break free in time to attempt a return to the Vahsel Bay area.

Although the scope for activity was limited, the dogs were exercised (and on occasion raced competitively), men were encouraged to take moonlight walks, and aboard ship there were attempted theatricals.

During this relative lull the ship drifted into the area where, in 1823, Captain Benjamin Morrell of the sealer Wasp reported seeing a coastline which he identified as "New South Greenland".

His first thought was for Paulet Island, where he knew there was a hut containing a substantial food depot, because he had ordered it 12 years earlier while organising relief for Otto Nordenskjöld's stranded Swedish expedition.

[59] Before the march could begin, Shackleton ordered the weakest animals to be shot, including the carpenter Harry McNish's cat, Mrs Chippy, and a pup which had become a pet of the surgeon Macklin.

[60] In three days, the party managed to travel barely two miles (3.2 km), and on 1 November, Shackleton abandoned the march; they would make camp and await the break-up of the ice.

[70] Food shortages became acute as the weeks passed, and seal meat, which had added variety to their diet, now became a staple as Shackleton attempted to conserve the remaining packaged rations.

[71] Meanwhile, the rate of drift became erratic; after being held at around 67° for several weeks, at the end of January there was a series of rapid north-eastward movements which, by 17 March, brought Patience Camp to the latitude of Paulet Island, but 60 nm (111 km) to its east.

It was apparent from high tide markings that this beach would not serve as a long-term camp,[80] so the next day Wild and a crew set off in the Stancomb Wills to explore the coast for a safer site.

Another whaling station was known to be at Prince Olav Harbour, just six miles (10 km) north of Peggotty Camp over easier terrain, but as far as the party was aware, this was only inhabited during the summer months.

He first left South Georgia a mere three days after he had arrived in Stromness, after securing the use of a large whaler, The Southern Sky, which was laid up in Husvik Harbour.

[101] After Shackleton left with the James Caird, Wild took command of the Elephant Island party, some of whom were in a low state, physically or mentally: Lewis Rickinson had suffered a suspected heart attack; Perce Blackborow was unable to walk, due to frostbitten feet; Hubert Hudson was depressed.

On the suggestion of Marston and Lionel Greenstreet, a hut—nicknamed the "Snuggery"—was improvised by upturning the two boats and placing them on low stone walls, to provide around five feet (1.5 m) of headroom.

[103] Wild initially estimated that they would have to wait one month for rescue, and refused to allow long-term stockpiling of seal and penguin meat because this, in his view, was defeatist.

[104] This policy led to sharp disagreements with Orde-Lees, the storekeeper, who was not a popular man and whose presence apparently did little to improve the morale of his companions, unless it was by way of being the butt of their jokes.

[108] Wild's thoughts were now seriously turning to the possibility of a boat trip to Deception Island—he planned to set out on 5 October, in the hope of meeting a whaling ship—[109] when, on 30 August 1916, the ordeal ended suddenly with the appearance of Shackleton and Yelcho.

Unable to return to McMurdo Sound, she remained captive in the ice for nine months until on 12 February 1916, having travelled a distance of around 1,600 miles (2,600 km), she reached open water and limped to New Zealand.

The remainder of the party reached the temporary shelter of Hut Point, a relic of the Discovery Expedition at the southern end of McMurdo Sound, where they slowly recovered.

[118] Shackleton accompanied the ship as a supernumerary officer, having been denied command by the governments of New Zealand, Australia and Great Britain, who had jointly organised and financed the Ross Sea party's relief.

Before the war ended, two—Tim McCarthy of the open boat journey and the veteran Antarctic sailor Alfred Cheetham—had been killed in action, and Ernest Wild, Frank's younger brother and member of the Ross Sea party, had died of typhoid while serving in the Mediterranean.

From the Endurance crew, Wild, Worsley, Macklin, McIlroy, Hussey, Alexander Kerr, Thomas McLeod and cook Charles Green all sailed with Quest.