Pattern 1853 Enfield

Such weapons manufactured with rifled barrels, muzzle loading, single shot, and utilizing the same firing mechanism,[2] also came to be called rifle-muskets.

The rifle's cartridges contained 2+1⁄2 drams, or 68 grains (4.4 g)[3] of gunpowder, and the ball was typically a 530-grain (34 g) Boxer modification of the Pritchett & Metford or a Burton-Minié, which would be driven out at approximately 1,250 feet (380 m) per second.

Later that year, the adventurer and mercenary William Walker imposed a military dictatorship in Nicaragua, reimposing slavery and threatening to conquer all of Central America.

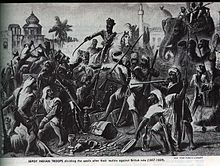

Sepoys in the British East India Company's armies in India were issued with the new rifle in 1857, and rumours were spread that the cartridges (referring here to paper-wrapped powder and projectile, not to metallic cartridges) were greased with beef tallow, pig fat, or a combination of the two – a situation abhorrent to Hindu and Muslim soldiers based on religious beliefs.

[9] The idea of having anything which might be tainted with pig or beef fat in their mouths was unacceptable to the Indian soldiers, and when they objected it was suggested that they were more than welcome to make up their own batches of cartridges, using a religiously acceptable greasing agent such as ghee or vegetable oil.

"[10] As a consequence of British fears, the Indian infantry's long arms were modified to be less accurate by reaming out the rifling of the Pattern 1853 making it a smooth bore[citation needed] and the spherical / ball shot does not require greasing, just a patch.

Special units called Forest Rangers were formed to fight rebels in the bush but after their first expedition into the bush covered hills of the Hunua ranges, south of Auckland, most Enfields were returned and replaced with a mixture of much shorter and lighter, Calisher and Terry breech loading carbines, and Colt Navy .36 and Beaumont–Adams .44 revolvers.

[12] Numbers of Enfield muskets were also acquired by the Maori later on in the proceedings, either from the British themselves (who traded them to friendly tribes) or from European traders who were less discriminating about which customers they supplied with firearms, powder, and shot.

The Confederates imported more Enfields during the course of the war than any other small arm, buying from private contractors and gun runners and smuggling them into Southern ports through blockade running.

Most soldiers were not trained to estimate ranges or to properly adjust their sights to account for the "rainbow-like" trajectory of the large calibre conical projectile.

Unlike their British counterparts who attended extensive musketry training, new Civil War soldiers seldom fired a single cartridge until their first engagement.

After the end of the war, hundreds of formerly Confederate Enfield 1853 muskets were sold from the American arms market to the Tokugawa shogunate, as well as some prominent Japanese domains including Aizu and Satsuma.

The Enfield 1853 rifle-musket is highly sought after by US Civil War re-enactors, British military firearms enthusiasts and black powder shooters and hunters for its quality, accuracy, and reliability.