Catholic Church in England and Wales

[3][4] Communion with Rome was restored by Queen Mary I in 1555 following the Second Statute of Repeal and eventually finally broken by Elizabeth I's 1559 Religious Settlement, which made "no significant concessions to Catholic opinion represented by the church hierarchy and much of the nobility.

The indigenous religion of the Britons under their priests, the Druids, was suppressed; most notably, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus launched an attack on Anglesey (or Ynys Môn) in 60 AD and destroyed the shrine and sacred groves there.

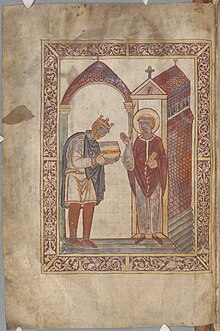

Having received the pallium earlier (linking his new diocese to Rome), Augustine became the first in the series of Catholic archbishops of Canterbury, four of whom (Laurence, Mellitus, Justus and Honorius) were part of the original band of Benedictine missionaries.

During this time of mission, Rome looked to challenge some different customs which had been retained in isolation by the Celts (the Gaels and the Britons), due in part to their geographical distance from the rest of Western Christendom.

For example, before Benedictine monk St. Dunstan was consecrated archbishop of Canterbury in 960; Pope John XII had him appointed legate, commissioning him (along with Ethelwold and Oswald) to restore discipline in the existing monasteries of England, many of which were destroyed by Danish invaders.

The village of Walsingham in Norfolk became an important shrine after a noblewoman named Richeldis de Faverches reputedly experienced a vision of the Virgin Mary in 1061, asking her to build a replica of the Holy House at Nazareth.

That is, there was no doctrinal difference between the faith of the English and the rest of Catholic Christendom, especially after calculating the date of Easter at the Council of Whitby in 667 and formalizing other customs according to the See of Rome.

[41] But on the other hand, failure to accept his break from Rome, particularly by prominent persons in church and state, was regarded by Henry as treason, resulting in the execution of Thomas More, former Lord Chancellor, and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, among others.

He disbanded monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland, appropriated their income, disposed of their assets, sold off artefacts stolen from them, and provided pensions for the robbed monks and former residents.

Under Queen Mary I, in 1553, the fractured and discordant English Church was linked again to continental Catholicism and the See of Rome through the doctrinal and liturgical initiatives of Reginald Pole and other Catholic reformers.

Throughout the alternating religious landscape of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, and Mary I, a significant proportion of the population (especially in the rural and outlying areas of the country) were likely to have continued to hold Catholic views, or were conservative.

The wording of the official prayer book had been carefully designed to make this possible by omitting aggressively "heretical" matter, and at first many English Catholics did in fact worship with their Protestant neighbours, at least until this was formally forbidden by Pope Pius V's 1570 bull, Regnans in Excelsis, which also declared that Elizabeth was not a rightful queen and should be overthrown.

"[70] So distraught was Elizabeth over Catholic opposition to her throne, she was secretly reaching out to the Ottoman Sultan Murad III, "asking for military aid against Philip of Spain and the 'idolatrous princes' supporting him.

Given that Douai was located in the Spanish Netherlands, part of the dominions of Elizabethan England's greatest enemy, and Valladolid and Seville in Spain itself, they became associated in the public eye with political as well as religious subversion.

It was this combination of nationalistic public opinion, sustained persecution, and the rise of a new generation which could not remember pre-Reformation times and had no pre-established loyalty to Catholicism, that reduced the number of Catholics in England during this period – although the overshadowing memory of Queen Mary I's reign was another factor that should not be underestimated (the population of the country was 4.1 million).

A mix of persecution and tolerance followed: Ben Jonson and his wife, for example, in 1606 were summoned before the authorities for failure to take communion in the Church of England,[77] yet the King tolerated some Catholics at court; for example George Calvert, to whom he gave the title Baron Baltimore (his son, Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore, founded in 1632 the Province of Maryland as a refuge for persecuted Catholics), and the Duke of Norfolk, head of the Howard family.

The Counter-Reformation on the continent of Europe had created a more vigorous and magnificent form of Catholicism (i.e., Baroque, notably found in the architecture and music of Austria, Italy and Germany) that attracted some converts, like the poet Richard Crashaw.

Generals, for example, did not deny Catholic men their Mass and did not compel them to attend Anglican services, believing that "physical strength and devotion to the military struggle was demanded of them, not spiritual allegiance".

Only after the Treaty of Paris in 1783, and in 1789 with the consecration of John Carroll, a friend of Benjamin Franklin, did the U.S. have its own diocesan bishop, free of the Vicar Apostolic of London, James Robert Talbot.

According to reviewer Aidan Bellenger, Glickman also suggests that "rather than being the victims of the Stuart failure, 'the unpromising setting of exile and defeat' had 'sown the seed of a frail but resilient English Catholic Enlightenment'.

Despite the resolute opposition of George IV,[122] which delayed fundamental reform, 1829 brought a major step in the liberalisation of most anti-Catholic laws, although some aspects were to remain on the statute book into the 21st century.

For example, American ministers to the Court of St. James's were often struck by the prominence of wealthy American-born Catholics, titled ladies among the nobility, like Louisa (Caton), granddaughter of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, and her two sisters, Mary Ann and Elizabeth.

A striking development was the surge in highly publicised conversion of intellectuals and writers including most famously G. K. Chesterton, as well as Robert Hugh Benson and Ronald Knox,[134] Maurice Baring, Christopher Dawson, Eric Gill, Graham Greene, Manya Harari, David Jones, Sheila Kaye-Smith, Arnold Lunn, Rosalind Murray, Alfred Noyes, William E. Orchard, Frank Pakenham, Siegfried Sassoon, Edith Sitwell, Muriel Spark, Graham Sutherland, Oscar Wilde, Ford Madox Ford,[135] and Evelyn Waugh.

Prominent cradle Catholics included the film director Alfred Hitchcock, writers such as Hilaire Belloc, Lord Acton and J. R. R. Tolkien and the composer Edward Elgar, whose oratorio The Dream of Gerontius was based on a 19th-century poem by Newman.

[147] Among others in this group are Paul Johnson; Peter Ackroyd; Antonia Fraser; Mark Thompson, Director-General of the BBC; Michael Martin, first Catholic to hold the office of Speaker of the House of Commons since the Reformation; Chris Patten, first Catholic to hold the post of Chancellor of Oxford since the Reformation; Piers Paul Read; Helen Liddel, a former British High Commissioner to Australia; and former Prime Minister's wife Cherie Blair.

[152] In 2019, Charles Moore, former editor of The Spectator, The Daily Telegraph, and authorized biographer of Margaret Thatcher, noted that his conversion in 1994 to Catholicism followed the Church of England's decision to ordain women, "unilaterally".

'"[157] And at Lambeth Palace, in February 2009, the Archbishop of Canterbury hosted a reception to launch a book, Why Go To Church?, by Fr Timothy Radcliffe OP, one of Britain's best known religious and the former master of the Dominican Order.

[185] Sizeable populations include North West England where one in five is Catholic,[186] a result of large-scale Irish immigration in the nineteenth century[187][188] as well as the high number of English recusants in Lancashire.

Worthy of note in this period was the Polish figure of The Venerable Bernard Łubieński (1846–1933) closely associated with Bishop Robert Coffin and who, after an education at Ushaw College, in 1864 entered the Redemptorists at Clapham and spent some years as a missionary in the British Isles, before returning to his native land.

From then on Polish services were regularly held in a chapel first in Globe Street, then in Cambridge Heath Road in Bethnal Green in the East End of London, where most exiled Poles were living at the time.